|

Algeria

Angola

Benin

Botswana

Burkina Faso

Burundi

Cameroon

Cape Verde

Central Afr. Rep.

Chad

Comoros

Congo (Brazzaville)

Congo (Kinshasa)

Côte d'Ivoire

Djibouti

Egypt

Equatorial Guinea

Eritrea

Ethiopia

Gabon

Gambia

Ghana

Guinea

Guinea-Bissau

Kenya

Lesotho

Liberia

Libya

Madagascar

Malawi

Mali

Mauritania

Mauritius

Morocco

Mozambique

Namibia

Niger

Nigeria

Rwanda

São Tomé

Senegal

Seychelles

Sierra Leone

Somalia

South Africa

South Sudan

Sudan

Swaziland

Tanzania

Togo

Tunisia

Uganda

Western Sahara

Zambia

Zimbabwe

|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

Cameroon: Speech, Rights, and Aging Autocracy

AfricaFocus Bulletin

December 18, 2017 (171218)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

Cameroonian-American writer Patrice Nganang, an acclaimed novelist who writes in

French and teaches at the State University of New York, Stonybrook, remains in prison

in Cameroon after his detention at the airport on December 6. His friends and

colleagues around the world have mobilized protests, which has evoked international

attention and pressure. But the aging autocracy of Cameroon President Paul Biya is

pressing charges against him, and is even more resistant to addressing the issues of

discrimination he highlighted in an article just a day before his arrest.

An on-line petition for his release has gained more than 7,500 signatures:

"Pour une liberté immédiate de Patrice Nganang, écrivain camerounais" Change.org

petition http://tinyurl.com/y6wo8u6t

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Announcement: this will be the last AfricaFocus Bulletin in 2017.

Publication will resume in mid or late January. The AfricaFocus website and

AfricaFocus Facebook page (https://www.facebook.com/AfricaFocus/) will continue to be updated.

Best wishes to all for the new year.

AfricaFocus continues to depend on support from readers. To make a donation, visit

http://www.africafocus.org/support.php

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Patrice Nganang https://nganang.com/

Additional background on Patrice Nganang and his arrest is available in the following

articles:

Mark Chiusano, "Activism lands Stony Brook professor Patrice Nganang in jail," AM New

York, Dec. 13, 2017 http://tinyurl.com/y8q9jdtv

"Cameroun: le procès de l'écrivain Patrick Nganang renvoyé au 19 janvier," France

24, December 15, 2017. http://tinyurl.com/ybghzwqf

Patrice Nganang, "Cameroun: carnet de route de l'écrivain Patrice Nganang en zone

(dite) anglophone," Jeune Afrique, 05 déc 2017 http://tinyurl.com/ybcmj223

Despite the attention to his individual case, and the need to continue that pressure,

it is notable that the issues of human rights, repression, and national unity in

Cameroon still have a very low international profile, despite warnings from

Cameroonian critics both inside the country and in the diaspora, and by human rights

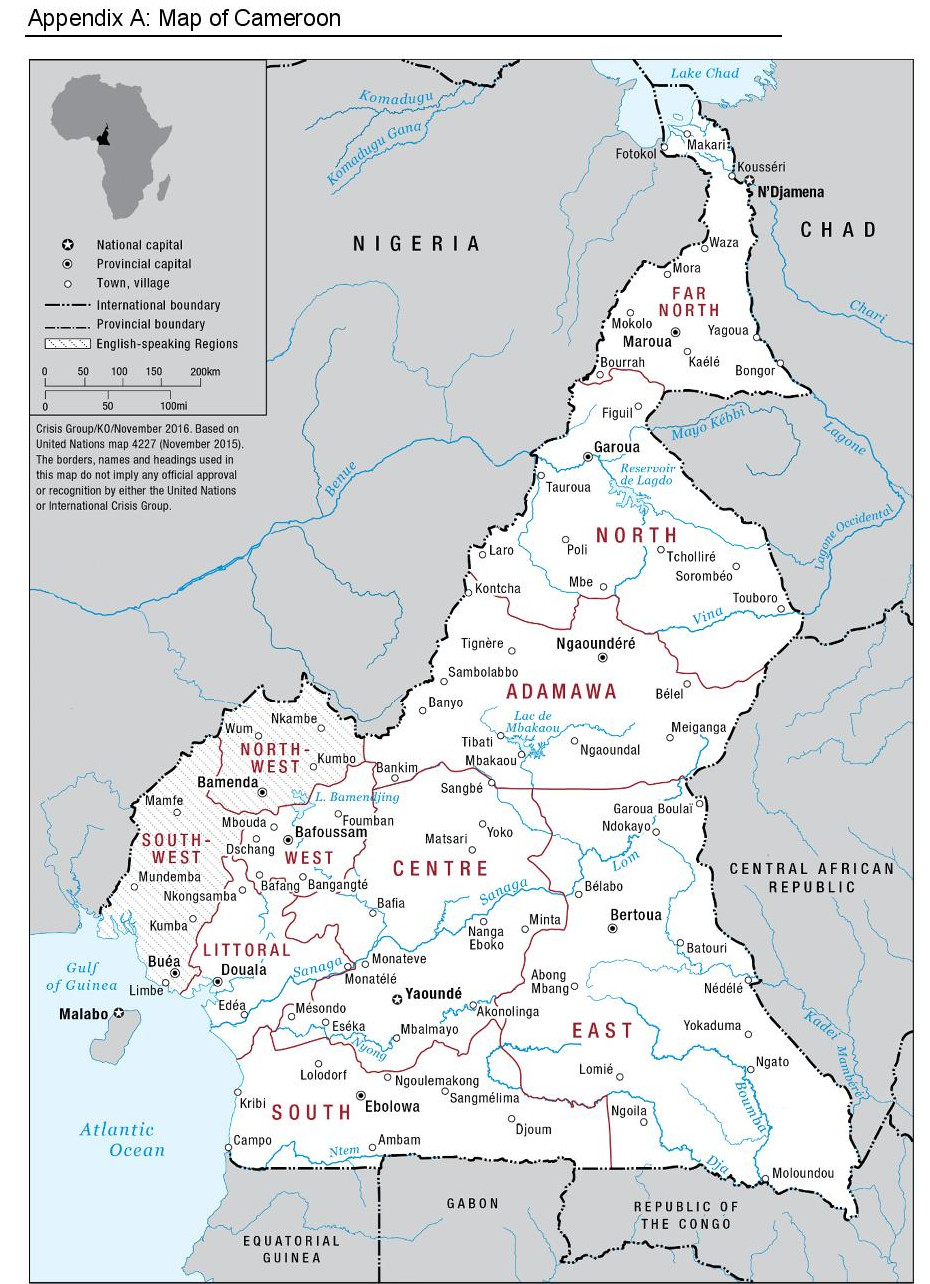

organizations. The Far North of Cameroon is a key battlefield in the terrorist

campaign of Boko Haram. The "Anglophone" regions adjacent to Nigeria in southern

Cameroon are the scene of rising discontent, brutal government repression, and

sporadic secessionist violence. And, after 35 years in power, the corrupt and

authoritarian regime of President Paul Biya, who spends long periods outside of the

country at his properties in France, is in its "twilight," although no one knows when

and how the end will come.

This AfricaFocus, in addition to the key links cited in this editor's note, includes

excerpts from two recent reports from the International Crisis Group, and translation

of selected excerpts from a commentary in Le Monde by Achille Mbembe, among the most

prominent African public intellectuals, who was born in Cameroon.

Amnesty International has released several recent reports detailing human rights

abuses both in the far North and the Anglophone regions.

https://www.amnesty.org/en/countries/africa/cameroon/

Specific reports include one on 13 October "Inmates 'packed like sardines' in

overcrowded prisons following deadly Anglophone protests" http://tinyurl.com/y9vavpm7

There is also extensive coverage of Cameroon by Reporters without Borders in Paris (

https://rsf.org/en/cameroon) and the Committee to Protect Journalists in New York. (

https://cpj.org/africa/cameroon/).

Particularly prominent is the case of RFI journalist Ahmed Abba, who was sentenced to

ten years in prison under Cameroon's anti-terrorism law for his news coverage of Boko

Haram.

The most detailed and reliable background analyses come from the International Crisis Group. Their

Cameroon page is at http://tinyurl.com/y9ypecjn

Profile of President Paul Biya at 30 years in power

BBC News, Yaounde, 6 November 2012

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-20219549

"Call for Proposals: Cameroon, The Stationary State," Politique Africaine, November

9, 2017

https://polaf.hypotheses.org/1912

This call for proposals, for an issue to be published in June 2018, is also a clear

analysis, with a bibliography, of the current status of research and analysis of the

current situation in Cameroon.

Achille Mbembe, "Au Cameroun, le crépuscule d'une dictature à huis clos" (the

twilight of a dictatorship behind closed doors), Le Monde, Oct. 9, 2017

http://tinyurl.com/ybg5mw3m

French text, see selected translated excerpts below.

For a previous AfricaFocus on repression of journalists and the shutdown of the

internet in Cameroon, see http://www.africafocus.org/docs17/med1704.php

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

Cameroon's Anglophone Crisis at the Crossroads

International Crisis Group, August 2, 2017

http://www.crisisgroup.org - Direct URL: http://tinyurl.com/yavwpre4

Executive Summary

The Anglophones of Cameroon, 20 per cent of the population, feel marginalised. Their

frustrations surfaced dramatically at the end of 2016 when a series of sectoral

grievances morphed into political demands, leading to strikes and riots. The movement

grew to the point where the government's repressive approach was no longer sufficient

to calm the situation, forcing it to negotiate with Anglophone trade unions and make

some concessions. Popular mobilisation is now weakening, but the majority of

Anglophones are far from happy. Having lived through three months with no internet,

six months of general strikes and one school year lost, many are now demanding

federalism or secession. Ahead of presidential elections next year, the resurgence of

the Anglophone problem could bring instability. The government, with the support of

the international community, should quickly take measures to calm the situation, with

the aim of rebuilding trust and getting back to dialogue.

Generally little understood by Francophones, the Anglophone problem dates back to the

independence period. A poorly conducted re-unification, based on centralisation and

assimilation, has led the Anglophone minority to feel politically and economically

marginalised, and that their cultural difference are ignored.

The current crisis is a particularly worrying resurgence of an old problem. Never

before has tension around the Anglophone issue been so acute. The mobilisation of

lawyers, teachers and students starting in October 2016, ignored then put down by the

government, has revived identity-based movements which date back to the 1970s. These

movements are demanding a return to the federal model that existed from 1961 to 1972.

Trust between Anglophone activists and the government has been undermined by the

arrest of the movement's leading figures and the cutting of the internet, both in

January. Since then, the two Anglophone regions have lived through general strikes,

school boycotts and sporadic violence.

Small secessionist groups have emerged since January. They are taking advantage of

the situation to radicalise the population with support from part of the Anglophone

diaspora. While the risk of partition of the country is low, the risk of a resurgence

of the problem in the form of armed violence is high, as some groups are now

advocating that approach.

The government has taken several measures since March - creating a National

Commission for Bilingualism and Multiculturalism; creating new benches for Common Law

at the Supreme Court and new departments at the National School of Administration and

Magistracy; recruiting Anglophone magistrates and 1,000 bilingual teachers; and

turning the internet back on after a 92-day cut. But the leaders of the Anglophone

movement have seen these measures as too little too late.

International reaction has been muted, but has nevertheless pushed the government to

adopt the measures described above. The regime in Yaoundé seems more sensitive to

international than to national pressure. Without firm, persistent and coordinated

pressure from its international partners, it is unlikely that the government will

seek lasting solutions.

The Anglophone crisis is in part a classic problem of a minority, which has swung

between a desire for integration and a desire for autonomy, and in part a more

structural governance problem. It shows the limits of centralised national power and

the ineffectiveness of the decentralisation program started in 1996. The weak

legitimacy of most of the Anglophone elites in their region, under-development,

tensions between generations, and patrimonialism are ills common to the whole

country. But the combination of bad governance and an identity issue could be

particularly tough to resolve.

Dealing with the Anglophone problem requires a firmer international reaction and to

rebuild trust through coherent measures that respond to the sectoral demands of

striking teachers and lawyers. There is some urgency: the crisis risks undermining

the approaching elections. In that context, several steps should be taken without

delay:

- The president of the republic should publicly recognise the problem and speak out

to calm tensions.

- The leaders of the Anglophone movement should be provisionally released.

- Members of the security forces who have committed abuses should be sanctioned.

- The government should quickly put in place the measures announced in March 2017,

and the 21 points agreed on with unions in January.

- The government and senior administration should be re-organised to better reflect

the demographic, political and historical importance of the Anglophones, and to

include younger and more legitimate members of the Anglophones community.

- The National Commission on Bilingualism and multiculturalism should be restructured

to include an equal number of Anglophones as Francophones, to guarantee the

independence of its members and to give it powers to impose sanctions.

- The government should desist from criminalising the political debate on Anglophone

Cameroon, including on federalism, in particular by ceasing to use the anti-terrorism

law for political ends and by considering recourse to a third party (the church or

international partner) as a mediator between the government and Anglophone

organisations.

In the longer term, Cameroon must undertake institutional reforms to remedy the

deeper problems of which the Anglophone issue is the symptom. In particular,

decentralisation laws should be rigorously applied, and improved, to reduce the

powers of officials nominated by Yaoundé, create regional councils, and better

distribute financial resources and powers. Finally, it is important to take legal

measures specific to Anglophone regions in the areas of education, justice and

culture.

Cameroon, facing Boko Haram in the Far North and militia from the Central African

Republic in the East, needs to avoid another potentially destabilising front opening

up. If the Anglophone problem got worse it would disrupt the presidential and

parliamentary elections scheduled for 2018. Above all, it could spark off further

demands throughout the country and lead to a wider political crisis.

Cameroon: A Worsening Anglophone Crisis Calls for Strong Measures

International Crisis Group

Nairobi/Brussels, 19 October 2017.

[Excerpt: Full briefing available at http://tinyurl.com/y9gktxzb]

IV. The Serious Political Consequences of the Violence

The violence seen in September

and October is unprecedented in the Anglophone regions of Cameroon. It has opened up

a rift between the government and the population, exacerbating the climate of

mistrust and making the idea of secession more attractive. The secessionist movement

probably still lacks support from the majority, but its proponents are now no longer

an insignificant minority. Anglo- phones increasingly take the view that secession

offers the best solution and it will be difficult to ignore their opinion within the

framework of an inclusive political dialogue, particularly since the secessionists

are now at the forefront of the Anglo- phone dispute. The violent incidents have also

increased backing for federalism, which has traditionally enjoyed Anglophone support.

In June, several federalists told Crisis Group that, in the absence of the federalism

they desired, they would settle for genuine decentralisation. But since the clashes

some of them no longer consider decentralisation as an acceptable middle-ground

solution.

Recent violent unrest has also aggravated pre-existing social tensions between

Anglophones and Francophones. Hate speech and attacks on Anglophones have both

proliferated since September, creating a palpably tense atmosphere. In state media,

the Southwest's governor referred to the protesters of 22 September as "dogs" and the

minister of communication described them as "terrorists". The pro-govern- ment media

and certain Francophone intellectuals imply that Anglophones are all secessionists.

Some journalists working for Vision 4 - a television channel financed by powerful

backers of the regime - consider the demonstrators to be terrorists and, in

September, advised the government "to call a state of emergency in the Anglophone

regions, make mass arrests, search houses (including those belonging to ministers),

and conduct surveillance operations on the Anglophones of Yaoundé". On Facebook, some

Francophones have celebrated the repression and number of deaths, while also vowing

more deaths on subsequent occasions.

After 22 September, Anglophones living in the Francophone parts of the country,

particularly in Yaoundé and Douala, have been targeted: arbitrary arrests in taxis,

house searches without warrants, and mass detentions of Anglophones have taken place

in Yaoundé neighbourhoods with large English-speaking communities such as in BiyemAssi,

Melen, Obili, Biscuiterie, Centre administratif and Etoug-Ebe. Many of these

arrests were made by police officers and gendarmes on 30 September. A number of

Anglophones have reported being insulted by Francophones in the markets. In their

places of work, Francophones have asked them "what were they still doing in Yaoundé

and why didn't they go back home to their filthy Bamenda?" Anglophones are suffering

a deep malaise as a result; they feel hated and more marginalised than ever before.

In the words of one Anglophone public official: "Perhaps the Francophones are right

about us spoiling their country. Now we need secession so that we can all live in

peace. That will bring back the peace". High- ranking Anglophones officials feel

under surveillance, and one of them said: "Here in the ministry everyone is

suspicious of everyone else. You have to be discreet, and keep to yourself". Feeling

watched, this elite has become more discreet and inward-looking.

The pro-federalist Social Democratic Front (SDF) - the largest opposition party,

winning 11 per cent of votes at the presidential elections of 2011, and with an

Anglophone leadership - has been subjected to strong pressure since the start of this

crisis. Initially it attempted to strike a moderate and conciliatory tone in order to

avoid losing support from its national Francophone base, but after the recent

violence, many of the party's deputies have symbolically announced their resignation

from the Cameroon parliament, without initiating the legal processes. The SDF's

national president has described the government's bloody repression of October as

genocide, calling for Paul Biya to be put on trial before the International Criminal

Court (ICC).

V. The Winding Path Toward a New Cameroon Consensus

Just as the government appears in denial about the depth of discontent facing it,

some leaders of the Anglophone protest movement appear detached from the country's

reality and international dynamics. Hence their often unrealistic demands, including

the call for secession. Meanwhile, the radicalisation of the dispute and increasing

support for secessionism is the fruit of the regime's initially disdainful approach

to corporatist demands, and of the bloody repression of protests since 2016, the

three-month internet shutdown (perceived by the Anglophones as a collective

punishment), and of the arrests of hundreds of protesters.

The regime allowed the situation to worsen as it hoped that protests would lose

momentum, while it alternated between violent repression and cosmetic concessions.

Currently the most powerful hardliners are betting on repression, and criticise the

president for having released some 50 militants in August; they are against

participating in any talks about federalism or even decentralisation, and some say

they are no longer willing to wait for the Anglophones to mount an armed insurrection

before "crushing" them. The more moderate see an effective decentralisation or even a

ten-state federation as a solution, though they don't dare say so in public as they

lack influence and fear being marginalised and considered as supporters of the

protest movement.

President Biya holds the cards needed to resolve this crisis, but he does not appear

genuinely interested in doing so. It falls to him to prevent a stalemate in Cameroon

that could lead to a political impasse one year before the presidential elections.

Signs exist of a possible armed uprising, given the continued multiplication of

violent groupings, acts of civil disobedience, and sporadic outbreaks of violence

(arson and home-made explosives). Some sources suggest that small groups of young

people have gone to Nigeria to be trained in guerrilla warfare, despite opposition

from Abuja to the principle of an independent Anglophone state, as it would risk

becoming a rear base for Nigerian secessionist movements.

Cameroon, which is engaged in a struggle against Boko Haram in the Far North and

against militias from the Central African Republic to the east, cannot afford a new

front, especially since an insurrection in the Anglophone region would probably have

repercussions in Douala and Yaoundé. The economic cost of overcoming such an

insurrection would be severe for a country currently under IMF adjustment measures

and that must organise general and presidential elections in one year's time, as well

as the African Cup of Nations Football competition.

International credit rating agencies are already concerned about Cameroon's political

climate. Fresh political troubles could lead to a downgrading of its sovereign credit

rating and make borrowing on the financial markets difficult. The political cost will

be high if the crisis drags on and more violence breaks out, because of the

difficulty if organising elections in the Anglophone regions. If the elections do

take place, the ruling party will most likely face a rout in those regions. Moreover,

any further violent clashes will only increase calls for international justice.

The Twilight of a Dictatorship behind Closed Doors

Achille Mbembe, Le Monde, October 9, 2017

http://tinyurl.com/ybg5mw3m

{Selected excerpts, translation by AfricaFocus]

[In addition to talking about President Biya] it is necessary to go beyond the

individual and take the exact measure of the system which he has put in place and

which is likely to survive him.

Because, in order to curb contestation and consolidate his grip on this country,

which was constantly threatened by the risk of impoverishment and decline of the

middle classes, by tribal fragmentation and the weight of patriarchal and

gerontocratic structures, he not only resorted to coercion. He also invented an

unprecedented method of managing state affairs that combined government with

abandonment and inertia, indifference and immobility, negligence and brutality, and

the selective administration of justice and penalties.

For its daily functioning and long-term reproduction, such a mode of domination

required, among other things, the miniaturization and systematization of both

vertical and horizontal forms of predation.

At the top, many senior officials and directors or board members of parastatals draw

directly from the public purse. At the bottom, poorly paid bureaucrats and soldiers

live off the population.

Niches for corruption proliferate and illegal activities are omnipresent in all

bureaucratic sectors and economic sectors.

In reality, everything provides an excuse for misappropriation and overvaluation,

whether it be the management of projects, procurement and implementation of public

contracts, compensation of any kind or transactions for everyday life.

The funds allocated to the ministries, delegated to the regions or transferred to

local authorities are hardly exempt. In thirty-five years of [Biya's] rule, the

number of contracts awarded over the counter and abandoned projects is in the

hundreds of thousands. In 2011, a document of the National Anti-Corruption Commission

estimated that between 1998 and 2004, at least 2.8 billion euros of public revenue

had been diverted.

...

[Mbembe is critical of the tendency of Anglophone secessionists to idealize the

history of British colonialism in comparison to French colonialism. But he strongly

criticizes the policies of the Biya regime.]

The intellectual weakness of the secessionist movement notwithstanding, there exists,

for historical and legal reasons, a singularity of the Anglophone question.

Recognition of this is a prerequisite for any resolution of the conflict.

Indeed, colonization has inherited two models of government. On the one hand, the

French command-model and, on the other hand, the Anglo-Saxon cooperative model, whose

indirect rule-law was the typical formula.

The francophonization of the state, institutions and political culture on the model

of commandism is indeed one of the reasons that led to the current stalemate.

How can one explain the relative absence of Anglophones in key positions in

government and their low representation in major power structures since

reunification? What to say about the frenzied policy of assimilation that has

resulted in the virtual abolition of their legal and educational systems and

reduction of the use of the English language in the day-to-day management of the

state and its symbols? And, for that matter, what concrete benefits have Anglophones

derived from the exploitation of oil, the main deposits of which are found on their

part of the territory?

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication providing reposted

commentary and analysis on African issues, with a particular focus on U.S. and

international policies. AfricaFocus Bulletin is edited by William Minter.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please write to this

address to suggest material for inclusion. For more information about reposted

material, please contact directly the original source mentioned. For a full archive

and other resources, see http://www.africafocus.org

|