|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

Africa/Global: How Women Lose from Tax Injustice

AfricaFocus Bulletin

September 25, 2017 (170925)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

A new report from the Association for Women in Development (AWID), authored by Dr.

Attiya Waris in Nairobi, makes a powerful case that women lose disproportionately

from illicit financial flows, which reduce the tax base and deprive states of the

resources to invest in critical public goods, and that addressing this issue is key

to efforts to combat gender inequality. The point should not be surprising, but too

often the impact of tax evasion and tax avoidance is cloaked in jargon that makes it

less visible than cases such as overt discrimination against women in employment and

wages. In contrast, this report stands out for its clarity. AfricaFocus strongly

recommends the full version, which is available on-line at

http://tinyurl.com/ych3zce3

This AfricaFocus Bulletin contains selected excerpts, as well as a short set of background

notes prepared by AfricaFocus on the context of related debates in the United States.

Two other examples highlighting the impact of illicit financial flows through tax

avoidance by multinational companies are reports by Action Aid (2010) on SAB Miller

in Ghana (http://tinyurl.com/ych3zce3) and on Associated British Foods (2013) in

Zambia http://www.africafocus.org/docs13/tax1302.php).

ActionAid also has a short (3.5 minute) animated video highlighting the impact of

this in the Zambia case (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ijtOErKjPMg). [Whether or

not you have time to read the reports, you can watch and share this video!]

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on tax injustice, illicit financial flows, and

related issues, visit http://www.africafocus.org/intro-iff.php

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

Illicit Financial Flows: Why We Should Claim These Resources for Gender, Economic and

Social Justice

by Dr Attiya Waris

Association for Women's Rights in Development (AWID)

July 28, 2017

http://www.awid.org Direct URL: http://tinyurl.com/ych3zce3

|

Editor's note: The conceptual distinction between a narrow and wider definition of illicit financial

flows is often confusing. This paper begins with a very clear short explanation and

justification for using the wider definition. For an earlier slightly longer

discussion, prepared by AfricaFocus Bulletin in November 2015, see "Defining Illicit

Financial Flows" http://tinyurl.com/yamhlajc

|

Concept and Scale of Illicit Financial Flows (IFFs)

The concept of illicit financial flows (IFFs) is characterised by a lack of a unique

consensual definition. Cobham, for example, explains the difference between a narrow

and wider definition as follows:

"There are two main definitions of illicit financial flows (IFF). One equates

'illicit' with 'illegal', so that IFFs are movements of money or capital from one

country to another that are illegally earned, transferred, and/or utilized. This

would include individual and corporate tax evasion but not avoidance (which is

legal), and other criminal activity like bribery or the trafficking of drugs or

people.

The other relies on the dictionary definition of 'illicit' as 'forbidden by law,

rules or custom' encompassing the illegal but also including the socially

unpalatable, such as the multinational corporate tax avoidance".

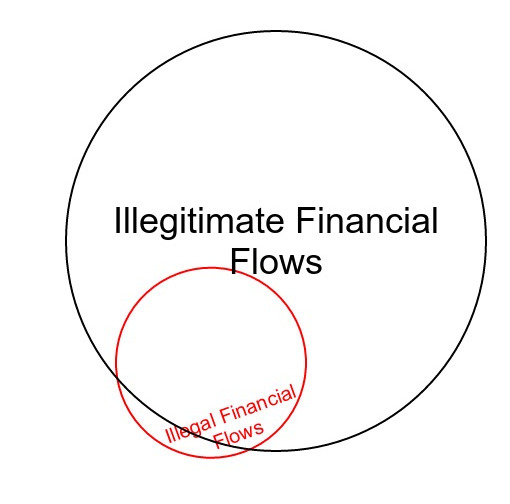

This Venn diagram shows the overlap between illegal and illegimate

financial flows. Almost all illegal flows are also illegitimate, with exceptions

such as family remittances which may bypass legal foreign currency laws.

For the purpose of this brief, we will use the broader definition that encompasses

tax evasion, particularly by multinational corporations (MNCs). This is because the

strong corporate lobby has largely shaped the very design of tax laws around the

world. Exercising their economic and political influence on countries, they can

define what type of tax avoidance is considered legal or illegal in different

countries according to their profit interests.

Illicit financial flows can be broken down into three main types:

- Proceeds from corrupt dealings: For example, bribes by corporations to secure

public contracts/permits or false declaration of corporate profits in order to evade

tax payment, especially by extractive industries such as mining and oil exploration.

- Proceeds from criminal activities: A system of bank secrecy is necessary to

conceal the origins of illegally obtained money (e.g. from human trafficking or sale

of illegal arms), typically by means of transfers involving foreign banks or

legitimate businesses a process known as "money laundering".

- Proceeds from commercial tax abuse: tax abuse includes both tax evasion and tax

avoidance by corporations and wealthy elites by using, for example, anonymous shell

companies in secrecy jurisdictions 4 that hide who the beneficial owners really are

and/or obscure information from tax authorities. Another form of commercial tax abuse

by MNC's is to over quote imports or under quote exports, to hide the real value of

products, and therefore profits a process known as "trade mispricing".

The exact amount of money being transferred through these systems is hard to

calculate, because IFFs can only be traced through the international banking system.

This does not account for money that simply moves from one place to another, within

or across to states, without the aid of the banking system, for example, cash in

exchange for political favors or ivory in exchange for small arms. While estimating

just how much money is lost through IFFs can be a difficult task due to the inherent

secrecy involved in their movement, there is consensus that they represent a

tremendous problem.

The Financial Transparency Coalition (FTC) released an infographic (http://tinyurl.com/yde4gqsa)

summarizing the different existing estimates. For

example, using data of trade misinvoicing, the Global Financial Integrity estimates,

that as much as 7.8 trillion was lost by developing and emerging countries to IFFs

from 2004 to 2013, and that this loss is getting bigger.

The landmark report of the High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa

(also known as the Mbeki report) estimates Africa to be losing more than $50 billion

annually in IFFs. This reality is having severe consequences to the development of

the continent. "Their economies do not benefit from the multiplier effects of the

domestic use of such resources, whether for consumption or investment. Such lost

opportunities impact negatively on growth and ultimately on job creation in Africa",

6 states the report.

To illustrate the effects on development, the same report cites a study (O'Hare and

others 2013) on the potential impact of IFFs on under- five child and infant

mortality in the region. "Without IFFs, the Central African Republic would have been

able to reach the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 4 on child mortality in 45 years

compared with the 218 years at current rates of progress. Other striking examples are

Mauritania, 19 years rather than 198 years; Swaziland, 27 years rather than 155

years; and the Republic of Congo, 10 years rather than 120 years. Perhaps most

striking is the finding that if IFFs had been arrested by the turn of the century,

Africa would reach MDG 4 by 2016" . The sheer amount shows that these lost'

resources could have assisted states nationally and regionally to achieve the unmet

Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Moving forward, this could play a crucial role

in financing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and mobilizing the maximum

available resources to ensure the realization of human rights and social justice.

Efforts to quantify the gendered impact and implications of IFFs across the African

continent are needed more than ever. The African Women's Development and

Communication Network (FEMNET) in partnership with Trust Africa, set out an important

path in 2016 to strategically discuss with other organizations, how to effectively

address this problem and propose political solutions supported by global processes to

curb IFFs.

The Disproportionate Impact of IFFs on Gender Justice

Gender impacts of IFFs tend to be understood and studied at the national and even

local level, with scarce literature that focuses on the global impact of IFFs as an

obstacle to the realization of women's rights and gender justice.

We take a look at some specific impacts here:

Impact on delivery of social services

An inadequate tax collection system has a direct impact on a country's budget

deficit. The result has commonly been a reduction in key areas such as education,

health care, cares facilities, which has a direct impact on women and women-headed

households that are more vulnerable to national budget constraints.

Despite external constraints, decisions on budget spending at the national level are

highly political and gendered. The decision to choose between privileging certain

areas like militarization and propaganda over social spending on people's needs in

the areas mentioned above, is part of maintaining the status quo of power by local

and global elites. The lower the investment in education, the easier to control a

population kept on survival mode.

The feminisation of poverty is a persistent phenomenon in which women are

overrepresented amongst the most poor, with low-paid and poor-quality jobs. Because

of unequal gendered power relations and entrenched cultural stereotypes that define

women and girls identities and social roles, they predominantly do unpaid care work

across the world. This situation has an impact on the advancement of women and girls'

human rights It perpetuates their impoverishment, acting as an obstacle to women and

girls participation in the paid economy, political life and bodily and sexual

autonomy. For these reasons, women tend to be more dependent on public social

services, which have the capacity to shift the unpaid care burden that falls

disproportionately on their shoulders. Failure to mobilize public resources therefore

robs women and children of the much-needed public services, which reflects a lack of

recognition of the role of the care economy in subsidizing the entire economy.

Unemployment and under investment in the economy

When monies are illicitly transferred out of developing countries, the loss of public

resources impacts negatively the economic development of a country and ultimately job

creation. Similarly, when profits are illicitly transferred out of developing

countries, reinvestment and the concomitant economic expansion to create local jobs

are not taking place in these countries.

Lack of public investment has consequently led to lack of employment creation and

greater unemployment, hitting women particularly hard. According to 2016 ILO figures,

in many regions in the world, in comparison to men, women are more likely to become

and remain unemployed. They have fewer chances to participate in the labour force and

when they do often have to accept lower quality jobs. Women are typically the

first to lose their jobs and/or accept shorter hours and bad working conditions to

keep jobs.

Regressive fiscal policies

IFFs often trigger regressive tax policies countries facing budget deficit tend to

cover that through increased consumption taxes rather than taxing the wealthy.

Neoliberal assumptions that taxing the wealthy would result in the withdrawal of

private investment in a given economy have permeated so deeply in economic policy

decision-making, that putting profit over people has become an unquestionable reality

worldwide, even as it remains fundamentally a political decision. Increasing

consumption taxes is in many cases the less costly of options for governments (both

economically and politically). After all, media corporations will not attack them as

they would if they tax the wealthy and also because, unfortunately, in most cases

there is not enough of a 'counter-power' / people power to stop them.

A great way to get middle and even working class people to support governments that

will not invest in social welfare, is the argument that the impoverished don't pay

taxes and live off benefits that formalized workers sustain with their contributions.

The invisibility of consumer taxes, and of who pays them the most in proportion to

their income, is an effective tool for preserving the status quo. Countries that

refuse to put into place mechanisms to efficiently tax those with greater wealth and

income (both individuals and corporations) typically resort to indirect tax

mechanisms such as high rates of value added tax (VAT) that collect taxes from

consumer goods or services rather than from individuals or companies. These have a

particularly negative effect on informal workers and people living in poverty the

majority of whom are women as they spend a large part of their income on taxes for

the essential goods and services they consume to sustain livelihoods, perpetuating

the cycle of poverty and aid dependence.

Marta Luttgrodt, 48, sells SABMiller beer from her stall

in the shadow of the

company's Accra Brewery, Ghana. Photograph: Jane Hahn/Jane Hahn/ActionAid

A poignant example is the SAB Miller Case in Ghana where Marta, who sells beer at her

small stall in Accra, Ghana outside the SAB Miller factory, was paying more tax than

the factory right next to her informal stand. This situation does little to encourage

informal workers to register as formal workers, as this would further increase their

tax burden. As a result, this perpetuates a situation in which informal workers are

ineligible to receive social services like health and pension benefits; yet

corporations and large businesses with huge profits are not pushed to contribute to

building and sustaining the infrastructure for these same basic services.

Principles of Equality and non-discrimination

Tax policies can play a crucial role in reducing inequality and redistributing

resources in order to level the playing field as much as possible.

The failure to prevent corruption and the fact that tax amnesties continue to be

granted to large corporations, fuel the desire among common taxpayers to be part of

those that outwit the state and its tax administration.

Equitable and progressive tax policies, based on human rights, have the potential to

reduce inequalities and redistribute resources to achieve development goals and end

impoverishment. Yet the wealthy few access legal and financial advice and services to

better exploit tax loopholes, or open undeclared foreign bank accounts in low-tax

jurisdictions.

Reliance on debt and development cooperation

Hidden wealth also increases inequality between developed and developing countries.

For instance the African Tax Administration Forum estimates that up to one-third of

Africa's wealth is being held abroad. This wealth and its associated income are

beyond the reach of African tax authorities. It deprives countries of resources that

could be used to mitigate inequality, and further enrich donor countries, where it is

stored. This income could address the over-dependence on overseas development

assistance (ODA), and shift the balance of power between donor and recipient

countries; and enable self-determined development priorities and outcomes, rather

than those imposed by ODA conditionality, including trade conditions.

Threat to Women's Peace and security

Lost resources through IFFs often cannot be used legitimately and end up fuelling

criminal activity, including illegal arms trade, human trafficking of which 49% of

victims are women and 21% are girls 24 and other activities undermining peace and

human rights.

The data is patchy given the illegal nature of IFFs, but evidence gathered by many

including Cobham, the Tax Justice Network and the report of the High Level Panel on

Illicit Financial Flows out of Africa, noted that "IFF thrive on conflict and

insecurity and also exacerbate both, undermining the financial and political

prospects for effective states to deliver and support development progress."

Considering the well-documented impact that war and conflict has on women and girls,

the issue of IFFs is of outmost importance to tackle the financial enablers behind

conflict and militarization.

Resourcing for women's rights and gender justice

One of the biggest challenges facing the implementation of long agreed commitments on

human rights, women's rights and gender equality and related goals, like those

contained in Agenda 2030, is ensuring that resources are sufficiently allocated.

States have an obligation to mobilize the maximum available resources for the

realization of human rights. Progressive taxation plays a key role in mobilizing

public resources and is a key tool for addressing economic inequality, including

gender inequality. The hidden resources of illicit financial flows must be unlocked

and returned to bolster domestic resourcing of development goals and gender equality.

|

Editor's note: The following notes were prepared by AfricaFocus Bulletin as background for the visit

of a delegation to the United States by representatives of African trade unions &

civil society organizations, organized by the Solidarity Center and ITUC-Africa on September 20-30, 2017. The delegation,

which is visiting Washington, DC and the San Francisco Bay Area, is meeting with

activists and policymakers to exchange views on strategies to combat inequality, tax

injustice, and illicit financial flows. The delegation includes Joel Odigie,

Coordinator Human and Trade Union Rights, African Organisation of the International

Trade Union Confederation (ITUC-Africa); Caroline Mugalla, Executive Secretary, East African Trade

Union Confederation; Luckystar Miyandazi, Policy Officer African Institutions

Program, European Centre for Development Policy Management (ECDPM) and former Africa

Coordinator for Africa for ActionAid's tax justice program; and Gyekye Tanoh, head of

the Political Economy Unit at Third World Network Africa.

|

The United States and the International Debate on Illicit Financial Flows

In Africa, the High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows

(https://www.uneca.org/iff) and the Stop the Bleeding Campaign to End Illicit

Financial Flows from Africa (http://stopthebleedingafrica.org/) have put this term

and this issue on the agenda for African governments and civil society organizations

around the continent.

In contrast, the term is not very familiar even among policy analysts in the United

States, but the issues of tax justice, tax evasion, and tax avoidance are central to

debate in both political circles and among social justice organizations. The focus is

primarily on the domestic issue of how the rich do not pay their fair share. There is

also an understanding that this has an international dimension, but there is little

awareness of how the United States itself contributes to illicit financial flows.

The challenge is to make these connections. This background note provides several

resources useful for doing so.

The Financial Secrecy Index ranks jurisdictions according to their secrecy and the

scale of their offshore financial activities. A politically neutral ranking, it is a

tool for understanding global financial secrecy, tax havens or secrecy jurisdictions,

and illicit financial flows or capital flight.

An estimated $21 to $32 trillion of private financial wealth is located, untaxed or

lightly taxed, in secrecy jurisdictions around the world. Secrecy jurisdictions - a

term we often use as an alternative to the more widely used term tax havens - use

secrecy to attract illicit and illegitimate or abusive financial flows. Illicit

cross-border financial flows have been estimated at $1-1.6 trillion per year:

dwarfing the US$135 billion or so in global foreign aid. Since the 1970s African

countries alone have lost over $1 trillion in capital flight, while combined external

debts are less than $200 billion. So Africa is a major net creditor to the world -

but its assets are in the hands of a wealthy élite, protected by offshore secrecy;

while the debts are shouldered by broad African populations.

Top 15 countries: 1. Switzerland, 2. Hong Kong, 3. USA, 4. Singapore, 5. Cayman

Islands, 6. Luxembourg, 7. Lebanon, 8. Germany, 9. Bahrain, 10. United Arab Emirates

(Dubai), 11. Macao, 12. Japan, 13. Panama, 14. Marshall Islands,

15. United Kingdom

"Many U.S. corporations use offshore tax havens and other accounting gimmicks to

avoid paying as much as $90 billion a year in federal income taxes. A large loophole

at the heart of U.S. tax law enables corporations to avoid paying taxes on foreign

profits until they are brought home. Known as "deferral," it provides a huge

incentive to keep profits offshore as long as possible.

Deferral gives corporations enormous incentives to use accounting tricks to make it

appear that profits earned here were generated in a tax haven. Profits are funneled

through subsidiaries, often shell companies with few employees and little real

business activity. Effectively, firms launder U.S. profits to avoid paying U.S.

Taxes."

Background notes on tax justice and illicit financial flows in U.S. political context

Prepared by AfricaFocus Bulletin for

Solidarity Center Mini-Symposium, September 28, 2017

Africa & the U.S.: Illicit Financial Flows, Tax Justice, and Economic Inequality

The "tax reform" debate

"The big battle throughout the fall will be taxes. The Republicans are trying to

decide whether to go for massive tax cuts--particularly for corporations, which are

awash in cash, and the rich--or massive tax cuts plus an overhaul of the tax system

that will permanently favor the wealthy and the corporations (and probably hurt the

middle class)." - Brooklyn College political scientist Corey Robin, Facebook post,

September 2, 2017 https://www.facebook.com/corey.robin1/posts/1488929127839470

"It's a Myth That Corporate Tax Cuts Mean More Jobs," by Sarah Anderson

The New York Times, August 30, 2017

http://tinyurl.com/y8fqapyq

"The arithmetic for us is simple," AT&T's chief executive, Randall Stephenson, said

on CNBC in May. If Congress were to cut the 35 percent tax on corporate profits to 20

percent, he declared, "I know exactly what AT&T would do -- we'd invest more" in the

United States. Every $1 billion in tax savings would create 7,000 well-paying jobs, Mr. Stephenson

went on to say. The correlation between lower corporate taxes and more jobs, he

assured viewers, runs "very, very tight."

As Congress prepares to take up tax legislation this fall, including an effort to

reduce the corporate tax rate, this bold jobs claim merits examination. Notably, it

comes from the chief executive of a company that's already paying comparatively

little in federal taxes.

According to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, AT&T enjoyed an effective

tax rate of just 8 percent between 2008 and 2015, despite recording a profit in the

United States each year, by exploiting tax breaks and loopholes. (The company argues

that it pays significant taxes, at a rate close to 34 percent in recent years, but

that includes deferred taxes and state and local levies.) Despite the enormous

savings AT&T has realized, the company has been downsizing. Although it hires

thousands of people a year, the company, by our analysis at the Institute for Policy

Studies, reduced its total work force by nearly 80,000 jobs between 2008 and 2016,

accounting for acquisitions and spinoffs each involving more than 2,000 workers.

Institute for Policy Studies report: "Corporate Tax Cuts Boost CEO Pay, Not Jobs"

http://www.ips-dc.org - Direct URL: http://tinyurl.com/y7fdkovy

3-minute video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EIdOkaeqe2E

House Speaker Paul Ryan is proposing to cut the statutory federal corporate tax rate

from 35 to 20 percent. President Trump wants to slash the rate even further, to just

15 percent. Their core argument? Lowering the tax burden will lead to more and better

jobs.

To investigate this claim, this report is the first to analyze the job creation

records of the 92 publicly held U.S. corporations that reported a U.S. profit every

year from 2008 through 2015 and paid less than 20 percent of these earnings in

federal income tax. Did these reduced tax rates actually lead to greater employment

within the 92 firms? The data we have compiled give a definitive -- and sobering --

answer.

The money-laundering debate and the Trump investigation

Dan Froomkin, "Trump's World of Luxury Real Estate is Fueled by Money-Laundering"

American Constitution Society Blog, August 31, 2017

Brief excerpt. Full article at: http://tinyurl.com/y93w93f8

The ultra-high-end real estate business, where Donald Trump made a lot of his money,

is the easiest place for oligarchs and others to launder large amounts of illicit

cash. And because several of the lawyers on special counsel Robert Mueller's team

investigating Russian connections with the Trump presidential campaign are

specialists in money-laundering and other financial crimes, some observers are

speculating that he may be looking into Trump's past business dealings to see if any

of those connections are relevant to the matter at hand.

The fact that money-launderers flock to luxury real estate is nothing new, and isn't

much of a mystery either. It's the direct result of a major loophole in U.S.

government rules that require banks to report cash deposits over $10,000 -- but allow

property owners to accept $10 million in cash for a condo without divulging who gave

it to them.

...

For fraudsters, drug cartels, oligarchs and corrupt foreign government officials

looking for a way to launder huge sums of illicit cash -- and park it somewhere safe

-- high-end real estate is the investment of choice. "You can put a lot of money in

one place at one time, without raising any eyebrows," says Heather Lowe, legal

counsel for the dirty-money watchdog group Global Financial Integrity. The Treasury

Department explains it this way: "The real estate market can be an attractive vehicle

for laundering illicit gains because of the manner in which it appreciates in value,

'cleans' large sums of money in a single transaction, and shields ill-gotten gains

from market instability and exchange-rate fluctuations."

A New York Times series in 2015 found that more than half of the $8 billion spent

each year on New York residences that cost more than $5 million comes from shell

corporations that mask the real owners' identities, one possible sign of moneylaundering.

Global Witness, "Undercover in New York," January 2016

https://www.globalwitness.org/shadyinc/

"We went undercover and approached 13 New York law firms. We deliberately posed as

someone designed to raise red flags for money laundering. We said we were advising an

African minister who had accumulated millions of dollars, and we wanted to buy a

Gulfstream Jet, a brownstone and a yacht. We said we needed to get the money into the

U.S. without detection.

To be clear, the meetings with the lawyers were all preliminary. None of the law

firms took our investigator on as a client, and no money was moved. Nonetheless, the

results were shocking; all but one of the the lawyers had suggestions on how to move

the funds. To see what some of them said, watch [this 3-minute video]:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j8pgI60GrvU

Current Congressional Legislation related to Illicit Financial Flows and Tax Justice

Corporate Transparency Act of 2017

A bill to amend title 31, United States Code, to ensure that persons who form

corporations or limited liability companies in the United States disclose the

beneficial owners of those corporations or limited liability companies, in order to

prevent wrongdoers from exploiting United States corporations and limited liability

companies for criminal gain, to assist law enforcement in detecting, preventing, and

punishing terrorism, money laundering, and other misconduct involving United States

corporations and limited liability companies, and for other purposes.

S. 1717: Sponsor Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR), 1 cosponsor, Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL)

https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/115/s1717

H.R. 3089: Sponsor Rep. Carolyn Maloney (D-NY), 10 cosponsors (5R, 5D)

https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/115/hr3089

Related background on beneficial ownership

https://thefactcoalition.org/issues/incorporation-transparency

Stop Tax Haven Abuse Act

A bill to end offshore corporate tax avoidance, and for other purposes.

Summary: This bill authorizes the Department of the Treasury to impose restrictions

on foreign jurisdictions or financial institutions to counter money laundering and

efforts to significantly impede U.S. tax enforcement. It amends the Internal Revenue

Code to expand reporting requirements for certain foreign investments and accounts

held by U.S. persons, and amends the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 to: (1) require

corporations to disclose certain financial information on a country-by-country basis,

and (2) impose penalties for failing to disclose offshore holdings.

S. 841: Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI), no cosponsors

https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/115/s851

H.R. 1932: Rep. Lloyd Doggett (D-TX), 59 cosponsors, all Democrats

https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/115/hr1932

Related background on country-by-country reporting

https://thefactcoalition.org/resources/country-by-country-reporting

Inclusive Prosperity Act of 2017

A bill to impose a tax on certain trading transactions to invest in our families and

communities, improve our infrastructure and our environment, strengthen our financial

security, expand opportunity and reduce market volatility.

S. 805: Sen. Bernard Sanders (D-VT), no cosponsors

https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/115/s805

H.R. 144: Rep. Keith Ellison (D-MN), 23 cosponsors, all Democrats

https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/115/hr1144

Related background on financial transaction ("Robin Hood") taxes

http://www.robinhoodtax.org/how/everything-you-need-to-know

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication providing reposted

commentary and analysis on African issues, with a particular focus on U.S. and

international policies. AfricaFocus Bulletin is edited by William Minter.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please write to this

address to suggest material for inclusion. For more information about reposted

material, please contact directly the original source mentioned. For a full archive

and other resources, see http://www.africafocus.org

|