|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

Zambia: From Democracy to Dictatorship?

AfricaFocus Bulletin

April 25, 2017 (170425)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

"Our country is now all, except in designation, a dictatorship

and if it is not yet, then we are not far from it. Our political

leaders in the ruling party often issue intimidating statements that

frighten people and make us fear for the immediate and future. This

must be stopped and reversed henceforth." - Zambia Conference of

Catholic Bishops, April 23, 2017

This AfricaFocus Bulletin contains three short commentaries on the

current political crisis in Zambia, by Simon Allison, Nic Cheeseman,

and Tendai Biti. Another AfricaFocus, also to be sent out today,

focuses on the wider African and global context of "media repression

2.0" in the internet era, including a report on attacks on press

freedom in Zambia.

The statement cited above from the Catholic Bishops of Zambia is

available at http://tinyurl.com/l9cepug

The Council of Churches in Zambia has also issued a strong statement

condemning the arrest of opposition leader Hakainde Hichilema (http://tinyurl.com/my4a6kx).

For keeping up with recent news on Zambia, two key sources are

http://allafrica.com/zambia and The Mast (

https://www.facebook.com/themastzambia/ or

https://www.themastonline.com/, successor to The Post, which was

shut down by the government in 2016.

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on Zambia, visit

http://www.africafocus.org/country/zambia.php

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

Analysis: Dark, dangerous days for Zambia's democracy

After the attack on the home of Zambia's opposition leader, and then

his arrest on spurious charges, Zambia's reputation as a beacon of

democracy in Africa is under serious threat.

by Simon Allison

Daily Maverick, 20 April 2017

https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/ - direct URL:

http://tinyurl.com/lxls8nq

Hakainde Hichilema is famously suspicious. The Zambian opposition

leader travels with a phalanx of bodyguards, and often brings his

own food wherever he goes, just in case anyone wants to poison him.

He claims to have received repeated death threats. He has a safe

room installed in his house.

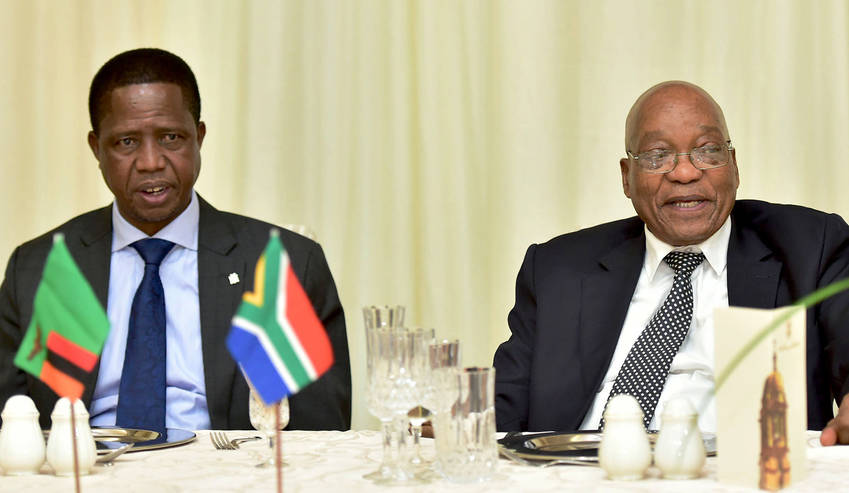

Zambian President Edgar Lungu meeting with President Jacob Zuma

on state visit to South Africa in December 2016

Until Tuesday last week, it was easy to dismiss Hichilema's paranoia

as exactly that paranoia. This is Zambia, after all, one of

Africa's most established and most successful democracies. No one

bumps off opposition leaders in Zambia. It's not Russia, or

Venezuela, or Tunisia.

Until Tuesday last week, it was easy to dismiss Hichilema's paranoia

as exactly that paranoia. This is Zambia, after all, one of

Africa's most established and most successful democracies. No one

bumps off opposition leaders in Zambia. It's not Russia, or

Venezuela, or Tunisia.

And then, in the early hours of that Tuesday morning, everything

changed. For Hichilema, and for Zambia.

Dozens of armed police descended onto Hichilema's property. They

broke down the door. They threw tear gas into the house. Dazed and

confused, and above all scared, the politician and his family

retreated into the safe room.

I spoke to him there, on the phone. He didn't raise his voice above

a whisper, and it trembled as he talked. He said that his wife and

children were injured from the tear gas, which was periodically

pumped through the vents of the safe room in a bid to force them

out, and that his servants had been tortured. He said he could hear

their screams. "This guy is trying to kill me," he said. "This guy

is a dictator, a full-blown dictator."

He was talking, of course, about President Edgar Lungu.

The siege lasted until mid-morning. By then, Hichilema's legal team

had arrived, as had journalists. His lawyers eventually coaxed

Hichilema out of the safe room. He was immediately arrested, and

charged shortly afterwards with treason.

No one is dismissing Hichilema's paranoia now and no one is quite

sure what would have happened in the absence of that safe room into

which he could retreat.

What we do know is that Hichilema's arch-rival, Lungu, has now

abandoned all democratic niceties in a bid to consolidate his grip

on power.

It was the nature of Hichilema's arrest that was most concerning:

the midnight raid, the tear gas, the casual brutality meted out to

the servants. It was all entirely unnecessary. Hichilema is a public

figure, and could have been quietly arrested at any time. But the

raid was designed to intimidate, to send an unmistakeable message to

the president's opponents that Lungu's authority shall no longer be

challenged.

It wasn't just Hichilema, either. Chilufya Tayali, head of the

Economic and Equity Party and a vocal critic of President Lungu, was

arrested just two days later. His crime? A Facebook post in which he

criticised the "inefficiency" of Zambia's police chief. He has

subsequently been released on bail.

If that sounds ridiculous well, it is. But not as ridiculous as

the charges levelled against Hichilema, which are so far entirely

unsubstantiated by evidence or detail. The only concrete allegation

is that Hichilema endangered the president's life when his vehicles

did not give way to the president's motorcade at a cultural

festival.

In Lungu's Zambia, a traffic incident has somehow become treason.

It's not Lungu's Zambia quite yet, however, as embarrassed

government prosecutors learned in court. In their submissions

against Hichilema, prosecutors made a Freudian slip, referring to

the opposition leader's alleged offences against the "Government of

President Edgar Lungu". They were forced to amend the charge sheet

when the defence observed that such an institution does not exist:

there is still only a Government of the Republic of Zambia, as much

as President Lungu might like it to be otherwise.

But make no mistake: these are dark, dangerous times for Zambia. And

if Lungu's end goal really is to dismantle the country's hard-won

democracy, then it's hard to see who or what will stop him.

Domestically, the arrests of Hichilema and Tayali, along with a

sustained assault on independent media, will have a chilling effect

on civil society. It will take extraordinary courage and commitment

to take on President Lungu's administration now.

Internationally too, Lungu faces remarkably little pressure. He has

already brushed off statements of concern from the United States and

the European Union, warning diplomats that they are "wasting their

time"; just as he brushed off concerns that his 2016 election win

was marred by serious electoral fraud.

South Africa, the regional superpower which does exert real

influence in Lusaka, has been deafeningly silent; as analyst Greg

Mills observed on these pages, it can't be a coincidence that Lungu

may well have been encouraged down this path by the example of the

"patronage regime" emerging in South Africa. The less leadership

South Africa displays at home, the less it can project abroad.

Zambia's in trouble. For so long a beacon of democracy in Africa,

its enviable reputation has already been tarnished by President

Lungu's actions. The risk now is that Lungu undoes that democratic

progress entirely.

If this all sounds a little paranoid, just remember that Hakainde

Hichilema was paranoid too. And on this, he is being proved right.

Zambia: President Lungu sacrifices credibility to repress opposition

by Nic Cheeseman

Democracy in Action, 21 April 2017

http://democracyinafrica.org/ - direct URL:

http://tinyurl.com/kqo4mr4

NicDiA's Nic Cheeseman looks at the political crisis in Zambia,

where the opposition leader has been charged with treason, and

analyses the prospects for democratic backsliding. Nic Cheeseman

(@fromagehomme) is the Professor of Democracy at the University of

Birmingham

Zambian President Edgar Lungu finds himself caught between a rock

and a hard place in both economic and political terms. As a result,

he has begun to lash out, manipulating the law to intimidate the

opposition, and in the process sacrificing what credibility he had

left after deeply problematic general elections in 2016.

Let us start with the economy, where the president is stuck in

something of a lose-lose position. On the one hand, his populace is

growing increasingly frustrated at the absence of economic job and

opportunities, while a number of experts have pointed out that the

country is on the verge of a fresh debt crisis. Economic growth was

just 2.9% in 2016, while the public debt is expected to hit 54% of

GDP this year, and the government cannot afford to pay many of its

domestic suppliers.

On the other, a proposed $1.2 billion rescue deal with the

International Monetary Fund (IMF) has the potential to increase

opposition to the government for two reasons. First, it would mean

significantly reducing government spending, including on some of

Lungu's more popular policies. Second, many Zambians are

understandably suspicious of IMF and the World Bank, having suffered

under previous adjustment programmes that delivered neither jobs nor

sustainable growth.

The president faces similar challenges on the political front.

Having won a presidential election in 2016 that the opposition

believes was rigged, and which involved a number of major procedural

flaws, Lungu desperately needs to relegitimate himself. However,

this need clashes with another, more important, imperative namely,

the president's desire to secure a third term in office when his

current tenure ends in 2020.

The problem for Lungu is that while it looks like he will be able to

use his influence over the Constitutional Court to ensure that it

interprets the country's new constitutional arrangements to imply

that he should be allowed to stand for a third term on the basis

that his first period in office was filling in for the late Michael

Sata after his untimely death in office, and so should not count

such a strategy is likely to generate considerable criticism from

the opposition, civil society and international community.

Lacking viable opportunities to boost his support base and

relegitimate his government, President Lungu has responded by

pursuing another strategy altogether: the intimidation of the

opposition and the repression of dissent. While in some ways

represents a continuation of some of the tactics used ahead of the

2016 election, when the supporters and leaders of rival parties were

harassed and in some cases detained, the recent actions of the

Patriotic Front (PF) government represent a worrying gear-shift.

Most obviously, opposition leader Hakainde Hichilema, who came so

close to leading his United Party of National Development (UPND) to

victory in the latest polls, has been arrested and his home raided.

His crimes? There appear to be two sets of charges. One set is

relatively mundane, and relates to an incident in which Hichilema is

accused of refusing to give way to the president's convoy. For this,

the opposition leader has been charged with breaking the highway

code and using insulting language.

The second charge that of treason is much more serious, but also

much less clear. Court documents state that Hichilema "on unknown

dates but between 10 October 2016 and 8 April 2017 and whilst acting

together with other persons unknown did endeavour to overthrow by

unlawful means the government of Edgar Lungu." Although this charge

has also been linked to the recent traffic incident, it seems more

likely to be motivated by the president's ongoing frustration that

the UPND continues to contest his election and refuses to recognise

him as a legitimately elected leader.

If this is the true motivation for the charges, it will only be the

latest of a number of moves to cow the opposition. For example, in

response to the refusal of UNPD legislators to listen to Lungu's

address to the National Assembly, Richard Mumba a PF proxy close

to State House petitioned the Constitutional Court to declare

vacant the seats of all MPs who were absent.

The opposition are not alone. Key elements of civil society have

also come under fire. As a result of the waning influence of trade

unions, professional associations now find themselves as one of the

last lines of defence for the country's fragile democracy, most

notably the Law Association of Zambia (LAZ). It should therefore

come as no surprise that a government MP, Kelvin Sampa, recent

introduced legislation into the National Assembly that would

effectively dissolve the LAZ and replace it with a number of smaller

bodies, each of which would be far less influential.

The bills introduced by Mumba and Sampa may not succeed, but in some

ways they don't need to. Their cumulative effect has been to signal

that those who seek to resist the governments are likely to find

themselves the subject of the sharp end of the security forces and

the PF's manipulation of the rule of law. The nature of Hichilema's

arrest is a case in point. Despite numerous opportunities to detain

him in broad daylight, armed police and paramilitaries planned a

night attack in which they switched off the power to the house,

blocked access to the main roads, and broke down the entrance gate.

Inside the property, the security forces are accused of firing tear

gas, torture, urinating on the opposition leader's bed and looting

the property.

It is therefore clear that the main aim of the operation was not an

efficient and speedy arrest, but rather the humiliation and

intimidation of an opponent.

Such abuses may help Lungu to secure the short-term goal of

prolonging his stay in power, but they will threaten to undermine

Zambia's future. It will or at least it should be politically

embarrassing for the IMF to conclude a deal with Zambia while the

opposition leader is on trial on jumped up charges and civil society

is decrying the slide towards authoritarian rule. Rumours now

circulating in Lusaka suggest that President Lungu may be preparing

to enhance his authority by declaring a State of Emergency in the

near future, which would further complicate the country's

international standing.

Lungu's blatant disregard for the rules of the democratic game also

has important implications for the county's political future. Many

Zambian commentators reported that the 2016 election was the most

violent in the country's history, and forecast rising political

instability if this trend was not reserved. Rather than heed this

warning, President Lungu appears determined to put this prophecy to

the test.

Zambia and Zimbabwe: Why fair elections are essential for Africa's

development

by Tendai Biti

Daily Maverick, 20 Apr 2017

https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/ - direct URL:

http://tinyurl.com/klunpsc

[Tendai Biti was finance minister of Zimbabwe under the unity

government from 2009-2013.]

Zimbabwe is used as a case study of a broken society; a country in

which those in power concern themselves only with maintaining power

and amassing wealth. Zimbabwe is also often cited as an exceptional

case. However, while it's situation undoubtedly has its own

peculiarities, Zimbabwe has not followed a path that is impassable

for others. It is dangerous to think otherwise.

Despite the popularity of the "Africa rising" narrative that has

sounded over the past decade regarding the pace of Africa's economic

growth and the prospects for development, the continent continues to

face significant challenges in unlocking the benefits for the

majority of its citizens.

While there is no singular reason for this, the one with the

greatest explanatory power is the mindset of self-enrichment at the

cost of social development among the elite. There is little doubt in

my mind that the solution to turning this around also lies in the

hands of leadership and the choices they make. And getting the right

leadership in place, to make the right choices, is a question of

democracy.

As a former minister of finance in Zimbabwe, the proposals that came

on to my desk for government financing of projects that would make a

significant impact on our country were countless. Yet there was

and continues to be absolutely no money made available by the

government for any of these projects. It was often a difficult pill

to swallow when all around the country malnourished families were

starving while the lavish lives of those in the president's innercircle

were there for all to see.

Zimbabwe is used as a case study of a broken society; a country in

which those in power concern themselves only with maintaining power

and amassing wealth. Zimbabwe is also often cited as an exceptional

case. However, while it's situation undoubtedly has its own

peculiarities, Zimbabwe has not followed a path that is impassable

for others. It is dangerous to think otherwise.

People often ask me how it is possible that we have been able to get

ourselves into this position as a country where everything is so

fundamentally broken. You cannot break things overnight, I answer,

but you can slowly chip away at the fundamentals and if no one does

anything to stop you then quite quickly all expectations of a

democratic society are abolished.

The increase in the number of elections taking place in Africa since

1990 has frequently been read as a positive indicator for the

continent's future development prospects. Elections are only a

necessary but not a sufficient component of democracy. Yet this is

undermined if the international community adopts the convenient

fallacy that at least by going through the motion of holding

elections a country will get it right eventually, and so the extent

to which they can become a smokescreen has largely been overlooked.

The frequency of elections is much easier to observe and tick off a

checklist than adherence to the rule of law. However, it is the rule

of law that determines a country's ability to function properly.

When the law is undermined and eroded, countries can follow a

downward spiral that leads to total collapse and from which it is

almost impossible to recover without outside support.

The rule of law in Zimbabwe has long been considered broken. The

same can now be said of our neighbour north of the Zambezi, Zambia.

Zambia's leadership seems intent on destroying the 50 years of work

post-independence to build democracy by replicating actions we have

routinely seen in Zimbabwe, notably the systematic harassment and

intimidation of press, civil society and the opposition. While in

the past Zambians have looked to the rule of law to protect their

rights when under threat, today they find there is little prospect

for protection or redress.

Zambia's major independent newspaper has been closed, with its

editor on the run; reports of intimidation and bribery of legal and

electoral officials have become widespread; and, now, as of a week

ago, popular opposition leader Hakainde Hichilema has been

incarcerated and charged with treason.

Shocking as this bold attempt to charge the opposition leader with

an offence that in theory could carry the death penalty appears, as

well as the violent and shocking manner in which the arrest was

conducted, if you look at the pattern of activity by the authorities

in recent months and years it is less surprising.

Over time Zambia's leadership has become more and more confident

that they can sit above the law. While cases in which people have

spoken ill of the president or alleged corruption in public

institutions result in arrests and court charges, justice is slow

and often elusive for those outside the ruling elite.

The manner in which last year's contested election was handled by

the Zambian authorities is a landmark case in this history. It's a

story of the cost of electoral authoritarianism. Today, with

Hichilema behind bars, it is also testament of how the region and

the international community missed a critical opportunity to stem a

tide of poor governance by speaking out against an electoral sham.

When Hichilema's party, the United Party for National Development,

challenged the 2016 election result on several grounds he was

advised to call on his supporters to remain peaceful and petition

the outcome in the courts, as is his constitutional right. The

petition was never heard, however, on the basis of a technicality

that his party continues to challenge through various appeals and

court submissions to this date.

This stands in stark contrast to how events played out in Ghana

following the 2012 elections. Then the opposition challenge of the

outcome led to a lengthy court case. While the outcome was

ultimately upheld by the court, the case revealed several failings

in the process for addressing ahead of future elections, and it

enabled the opposition a chance to present their evidence. The

process upheld the rule of law, and sent a clear signal to elites

and citizens alike that they can expect to be held accountable to

the law. This helped to pave the way for the peaceful transfer of

power to the opposition subsequently in January 2017.

The consequences of the soft approach of observers and the

international community following last year's contested elections in

Zambia appears to be coming back to haunt them, however. Their

cautious approach and hesitancy to challenge leadership has been

taken as a near enough blank check for the elite to step by step

deconstruct the rule of law.

While national sovereignty must be respected we must not forget that

if the government in question is itself undermining the rule of law

and the rights and safety of its own citizens then it has already

undermined the grounds for sovereignty in a democratic nation.

Moreover, the more states that are allowed to continue down this

path unchallenged, the fewer voices there are left to speak out

against such infractions and the more leaders elsewhere that will be

motivated to preserve their stay in power through illicit means. DM

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication

providing reposted commentary and analysis on African issues, with a

particular focus on U.S. and international policies. AfricaFocus

Bulletin is edited by William Minter.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. For more

information about reposted material, please contact directly the

original source mentioned. For a full archive and other resources,

see http://www.africafocus.org

|