|

Algeria

Angola

Benin

Botswana

Burkina Faso

Burundi

Cameroon

Cape Verde

Central Afr. Rep.

Chad

Comoros

Congo (Brazzaville)

Congo (Kinshasa)

Côte d'Ivoire

Djibouti

Egypt

Equatorial Guinea

Eritrea

Ethiopia

Gabon

Gambia

Ghana

Guinea

Guinea-Bissau

Kenya

Lesotho

Liberia

Libya

Madagascar

Malawi

Mali

Mauritania

Mauritius

Morocco

Mozambique

Namibia

Niger

Nigeria

Rwanda

São Tomé

Senegal

Seychelles

Sierra Leone

Somalia

South Africa

South Sudan

Sudan

Swaziland

Tanzania

Togo

Tunisia

Uganda

Western Sahara

Zambia

Zimbabwe

|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

West Africa/Europe: From Cocoa to Chocolate

AfricaFocus Bulletin

August 15, 2018 (180815)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

"Cocoa growing communities, particularly in West Africa, are facing poverty, child

labour and deforestation that have been made worse by a rapid fall in prices for

cocoa. Widely touted efforts in the cocoa industry to improve the lives of farmers,

communities and the environment made in the past decade are having little impact. In

fact, the modest scope of the proposed solutions does not even come close to

addressing the scale of the problem." - Cocoa Barometer, April 2018

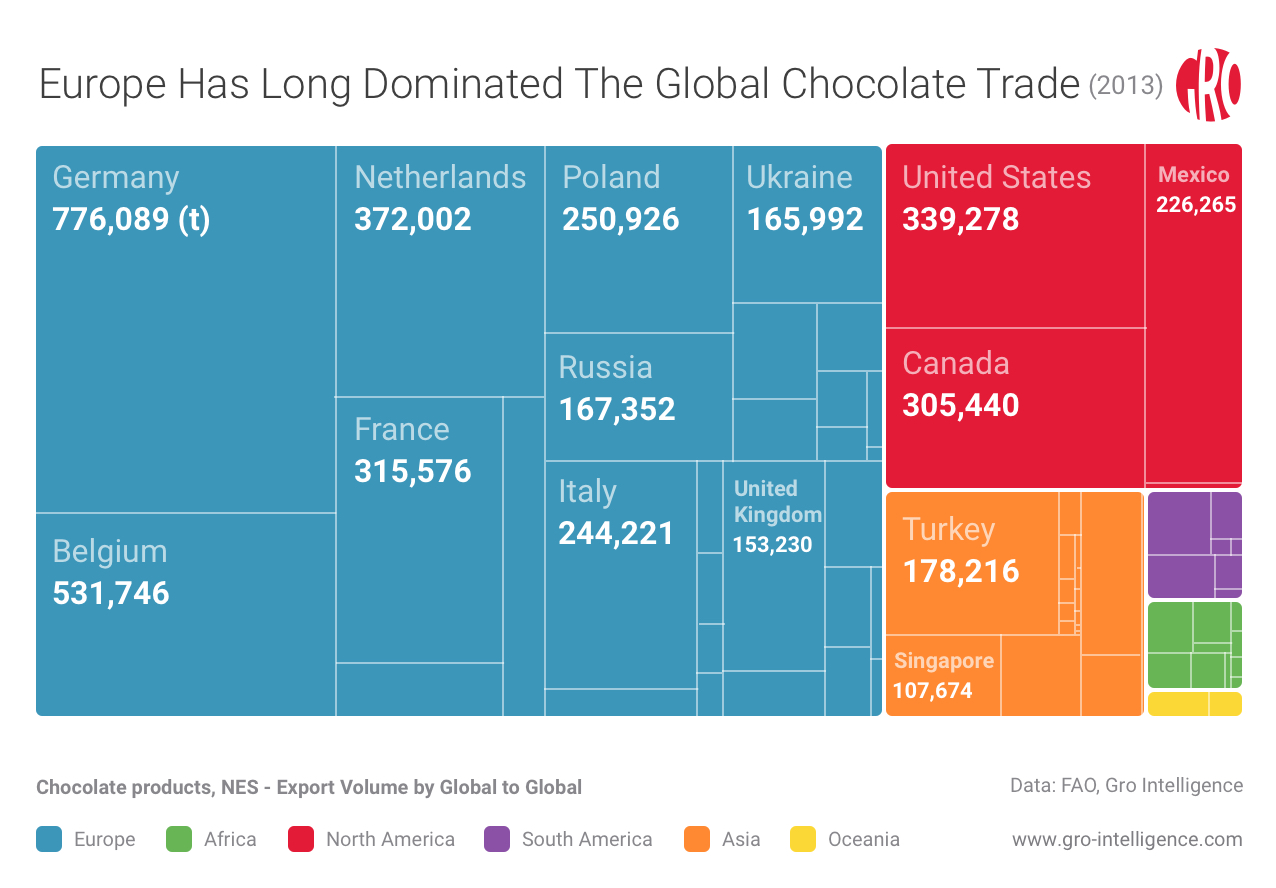

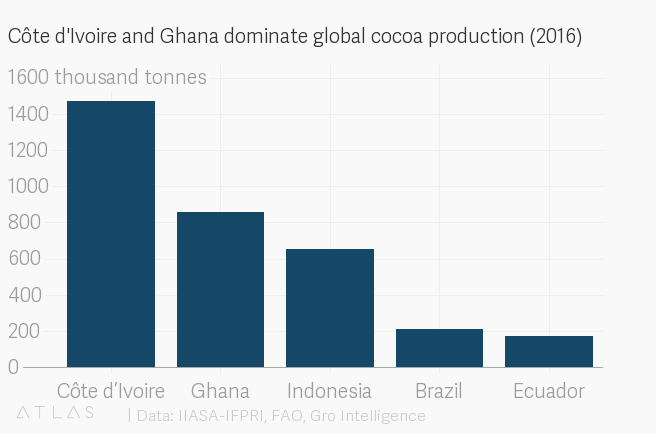

The global value chain from cocoa to the chocolate bars sold around the world and

consumed in largest quantities in rich countries features the same inequality today

as it has since the industrial expansion of the chocolate industry in the late 19th

century. Harvesting of cocoa beans is centered in West Africa, particularly in Ghana

and Côte d'Ivoire, while production of chocolate is concentrated above all in Western

Europe. Of the estimated total value of the industry of $100 billion, latest

estimates show that only about $6 billion go to the 4.5 to 5 million farmers who

cultivate the cocoa trees and harvest the beans.

This set of issues is now on the rise on the agenda not only for the chocolate industry and

its critics, but also national governments in West Africa and European parliamentarians.

Long-time activists in the fair trade movement and development organizations welcome

the new attention. But they also stress that large-scale changes will require strong

government actions and not just resolutions about "sustainability."

This AfricaFocus Bulletin contains several articles highlighting the current

situation and international debates about addressing these issues. Also included are

links to organizations promoting fair-trade chocolate, and in particular one

prominent initiative (Divine Chocolate) in which the Ghanaian cocoa farmers'

cooperative also owns shares in the company distributing the chocolate

internationally.

In addition to the articles excerpted below, two other articles highlight the new

trends, and are worth reading, despite likely over-optimistic language:

Ruth Maclean, "Moves to clean up chocolate industry are racing ahead," The Guardian,

26 Jul 2018 http://tinyurl.com/y74rwlss

Akinyi Ochieng, "The world's two largest cocoa producers want you to buy their

chocolate, not just their beans," Quartz Africa, May 12, 2017

http://tinyurl.com/yagnn2lc

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on agriculture and related issues, visit

http://www.africafocus.org/intro-ag.php

Russia Intervention in the Trump Election: Putting "Collusion" in Context

by William Minter

For almost two years now, Russian intervention has been the highest-profile, most

actively debated factor in the convergence of factors that led to the Trump

electoral win. But this nonstop media spotlight has often produced more heat than

light, with endless repetition of back-and-forth assertions of "no collusion"

versus "collusion." Many critics rightly note that talk about Russia has drowned

out needed discussion of the many domestic influences that contributed to Trump's

victory.

Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to ignore the documented realities and real

impact of Russian "active measures." ... It is also essential to find new paradigms for

understanding the Trump-Putin connection, which goes beyond personalities to new structural

alliances at the global level featuring the intersection of right-wing

politics, kleptocracy, and racism.

(continued)

Part of a series. The previous essay was on "Voter Suppression Matters

More Than You Think," and is available at

http://www.noeasyvictories.org/usa/voter-suppression.php

For additional context and background, see "Ten Ways to Misunderstand the Trump

Election, and Why They Still Matter" at

http://www.africafocus.org/docs18/usa1807.php,

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

The Bitter and Sweet: Dispatch from the 2018 World Cocoa Conference

Simran Sethi

http://tinyurl.com/y7cz4l3a

“Too many cocoa farmers are still living in poverty. Deforestation, child labour,

gender inequality, human rights violations and many other challenges are a daily

reality in many cocoa regions. We affirm the cocoa sector will not be sustainable if

farmers are not able to earn a living income.” This is the starting text of the new

Berlin Declaration, the culmination of the discussion from the 4th World Cocoa

Conference, a biannual event organized by the International Cocoa Organization (ICCO)

that explores the most important issues in cocoa and chocolate.

[See report from conference at

http://tinyurl.com/yc6fkms4]

Last week, more than 1,500 farmers, researchers, government representatives,

chocolate makers and manufacturers, and civil society groups involved in the cocoa

industry gathered in Berlin for the first time since the devastating price decline in

cocoa when global commodity prices for the crop plummeted by over 30 percent,

devastating the smallholder farmers who grow the majority of the world’s cocoa. “The

definition of sustainability,” explained ICCO Executive Director Jean-Marc Anga, “is

that all stakeholders should be able to make a decent living.”

But they can’t—and the problem isn’t new. Back in 2012, during the 2nd World Cocoa

Conference in Amsterdam, Dr. Anga shared a PowerPoint slide on how value is

distributed across the global cocoa economy. This year, he shared a slide with a

similar (meager) apportionment: Within a US$100 billion confectionary industry,

roughly US$6 billion is paid to farmers—a figure Dr. Anga contrasted with the US$15

billion distributed to governments as Value Added Taxes (VAT). The implications are

staggering: more money goes toward paying taxes on cocoa and chocolate than to the

farmers who spend years sustaining the crop.

Ninety percent of cocoa is grown by subsistence farmers working on modest plots of

land, the majority of whom live in West Africa and, according to a new report from

Fairtrade International, earn less than US$1 a day. As senior advisor Carla

Veldhuyzen van Zanten explained, more than half of cocoa households live below the

extreme poverty line.

This poverty underpins the greatest challenges in the sector, and is why Dr. Anga, as

well as the participants of the pre-conference civil society organized by the VOICE

Network (a group of nonprofit organizations and trade unions working on

sustainability in cocoa) prioritized the need for a living income for cocoa farmers.

Antonie Fountain, the managing director of the Network, summarized, “If poverty is

the key issue, then it should be a priority to solve it.”

What will this take? Patrick Esapa Enyong, president of the Southwest Farmers

Cooperative Union of Cameroon, explained during the conference track focused on

sustainable production, prosperous farmers, and thriving communities that it starts

with professionalization. Farmers need sustained access to land and credit, education

and technology, as well as improved planting materials and technical support so they

can advance agricultural practices and diversify what they grow. But, fundamentally,

they need equity. This was echoed by additional speakers and through participant

discussions and written commentary: “We must engage with farmers as equal partners,”

one wrote—not the “weakest link,” but decisionmakers who are fundamental to the cocoa

industry.

The current inequity and income disparity is why farmers are leaving cocoa in favor

of other crops and small-scale mining. “Farmers bear the risks of a volatile price,”

the 2018 Cocoa Barometer report from the VOICE Network (released to coincide with the

conference) states, “and there is no concerted effort by industry or governments to

alleviate even a part of the burden of this income shock.”

Doing so will require a number of steps. First and foremost, as Annemarie Matthess,

agricultural economist and program director for the German sustainable development

organization, GIZ, stressed, it must include an increase in the farmgate prices paid

to cocoa farmers (and an increase in payments made to those who work on cocoa farms),

as well as a focus on sustained, living incomes as a priority and key performance

indicator across the sector. But changes also have to come from the governments of

producing countries. Ivory Coast, Ghana, Indonesia, and Ecuador produce 75 percent of

the world’s cocoa. They should be able to work together, Dr. Anga explained, to

support the “people without whom we would not have chocolate.”

The Cocoa Barometer states that in countries where cocoa is grown, “there is a gap

between the claims and actual delivered services. For example, the Ghana [Cocoa

Board] has been shaken by corruption scandals in the last years, where millions of

dollars of public funds have been diverted. Transparency and accountability are

needed around public spending and support … for cocoa farmers.”

This transparency and accountability, of course, has to also extend to consuming

countries, manufacturers, and other members of the industry. This includes taking a

hard look at the mechanisms already in place. For example, anti-trust laws that are

supposed to keep companies from engaging in price collusion have become the fallback

reason manufacturers aren’t paying higher prices. But this can change; chocolate

companies and others in the supply chain can devise a plan to pay premiums—especially

when the cost of cocoa input plummets, as it did in 2016. (It’s important to note the

prices for our chocolates and candy bars remained steady.) Speculation on the futures

market (that contributes to price volatility) also has to be addressed. And

certifications have to be strengthened; they have not succeeded in measurably

improving the lives of farmers.

These are just a few of the issues covered at the World Cocoa Conference—and it is a

lot of information to take in. But a key takeaway for all chocolate lovers is that we

have a critical role to play in ensuring that the joy and deliciousness that comes

from chocolate is not borne out of environmental degradation and human suffering.

Every major chocolate manufacturer has committed to some degree of sustainability in

how they source cocoa. But this term means different things to different entities. As

Antonie Fountain reminds us, “Cocoa farming will not be sustainable until it can

provide a living income to farmers.”

“2018 Cocoa Barometer” Report Paints Dark Chocolate Picture: As Prices Fall, Woes

Rise for Farmers, Children, Forests

Not Sustainable: With Environmentally Damaging Overproduction and Insensitive

Approach by Producers, Cocoa Sector Efforts Fall Far Short of Addressing Poverty,

Deforestation, and Child Labour.

Berlin, April 19th, 2018

http://www.cocoabarometer.org/Cocoa_Barometer/Home.html

Cocoa growing communities, particularly in West Africa, are facing poverty, child

labour and deforestation that have been made worse by a rapid fall in prices for

cocoa. Widely touted efforts in the cocoa industry to improve the lives of farmers,

communities and the environment made in the past decade are having little impact. In

fact, the modest scope of the proposed solutions does not even come close to

addressing the scale of the problem. These are core conclusions of the 2018 Cocoa

Barometer, a biennial review of the state of sustainability in the cocoa sector.

Smallholder cocoa farmers in Cote d’Ivoire – the world’s biggest cocoa producer, who

are already struggling with poverty, have seen their income from cocoa decline by as

much as 36% over one year. That fact reflects the world market price for cocoa, which

saw a steep decline between September 2016 and February 2017. Farmers bear the risks

of a volatile price; and there is no concerted effort by industry or governments to

alleviate even a part of the burden of this income shock.

This price collapse was caused by overproduction of cocoa in the past years, at the

direct expense of native forests. This can be equally attributed to corporate

disinterest in the human and environmental effects of the supply of cheap cocoa, and

to an almost completely absent government enforcement of environmentally protected

areas.

In addition to often wrenching poverty for cocoa farmers, there is a host of other

problems:

- An average cocoa farmer in Côte d’Ivoire earns only a third of what he or she

should to earn a living income.

- More than ninety per cent of West Africa’s original forests are gone.

- Child labour remains at very high levels in the cocoa sector, with an estimated 2.1

million children working in cocoa fields in the Ivory Coast and Ghana alone. Child

labour is due to a combination of root causes, including structural poverty,

increased cocoa production, and a lack of schools and other infrastructure. Not a

single company or government is anywhere near reaching their commitments of a 70%

reduction of child labour by 2020.

- A “broken” market in which farmers have no real influence. While many of the

current programs in cocoa focus on technical solutions around improving farming

practices, the underlying problems at the root of the issues deal with power and

political economy, such as how the market defines price, the lack of bargaining power

farmers, market concentration of multinationals, and a lack of transparency and

accountability of both governments and companies.

“As long as poverty, child labour and deforestation are rife in the cocoa sector,

chocolate remains a guilty pleasure,” said Antonie Fountain, co-author of the

Barometer. “Current approaches will not solve the problem at scale. Companies and

governments need to acknowledge the urgency, and make a change. Efforts that cover

less than 50% cannot be called ‘solutions’.”

Recommendations for action in the report include the following:

- Make net income the key metric for all sustainability projects.

- Commit to a sector-wide goal of achieving a living income.

- Commit to a global moratorium on deforestation; focus on agroforestry and

reforestation as environmental solutions.

- Move from voluntary to mandatory requirements, on human rights as well as on

transparency and accountability.

- Develop sector-wide approaches at scale that address root causes to child labour.

- Increase urgency and ambition to reflect the scale of the problems, and implement

changes that also address issues around power and political economy, not just at

technical levels.

EU legislation must end child labour and deforestation in the cocoa supply chain

NGO coalition calls on EU policy-makers to protect tropical forests and the 2.1

million children working in cocoa

http://tinyurl.com/yd2f2pf3

Brussels, 10 July 2018 – A group of civil society organisations are calling on the EU

to pass legislation to end severe human rights violations and environmental

destruction in cocoa supply chains. The NGOs have joined forces ahead of the European

Parliamentary session “Cocoa and Coffee - devastating rainforests and driving child

labour: the role of EU consumption and how the EU could help”, to be held on July

11th.

The chocolate industry’s current approaches to eliminate child labour and to end

deforestation will not be sufficient without lawmakers creating a level playing

field. Voluntary schemes have played a key role in encouraging companies to introduce

more sustainable sourcing practices, but a lot more needs to be done. Urgent action

by lawmakers is required, including in the EU.

“Cocoa has been driving 30% of overall deforestation in Ivory Coast and Ghana, and

destroying other forests from Asia to the Amazon,” declared Etelle Higonnet of Mighty

Earth. Sergi Corbalán of the Fair Trade Advocacy Office added that cocoa must be good

for people as well as planet: “Child labour is a consequence of poverty. Better

prices must be paid to cocoa farmers to enable them to secure a living income.” Core

challenges will require legislation in both producing and consuming countries. “The

EU must rise to the challenge, as Europe is the number one importer, manufacturer,

and consumer of chocolate worldwide – and home to the biggest chocolate companies,”

explained Julia Christian of Fern.

The NGO coalition calls on the EU to make mandatory compliance with Human Rights Due

Diligence (HRDD) standards. HRDD would require chocolate companies to analyse,

prevent, mitigate, remediate and report on risks in their supply chain, not only for

their own operations, but also for those of their suppliers. It would require

mandatory reporting on key measures, such as responsible risk management (on child

labour, this would mean reporting on cases and on measures taken to address them).

Future reporting should be based on standard, common definitions, which requires

harmonisation of legislation across different jurisdictions and markets to avoid a

regulatory fragmentation.

“To end deforestation for cocoa, we also call on EU to urgently develop import

regulations that require companies and importers of cocoa to undertake responsible

sourcing and proper due diligence to ensure that the cocoa they are importing is not

coming from illegally cleared forests,” added Obed Owusu-Addai of EcoCare Ghana.

Just two months ago in the final declaration of the fourth World Cocoa Conference

held in Berlin, the cocoa sector itself recognised that ‘voluntary compliance has not

led to sufficient impact’, and that ‘all stakeholders are called upon to strengthen

human rights due diligence across the supply chain, including through potential

regulatory measures by governments.'

As such, the NGO coalition calls upon the EU Parliament and Commission to pass

legislation protecting against human rights violations and deforestation in the cocoa

sector.

Signed by: EcoCare Ghana, Fair Trade Advocacy Office, Fern, Mighty Earth, Oxfam,

VOICE Network. For further information, please contact Julia Christian of FERN at

julia@fern.org / Mob: (+32) 487 8585 29 or Antonie Fountain at

antonie@voicenetwork.eu / Mob: (+31) 06 242 765 17

Why Europe dominates the global chocolate market while Africa produces all the cocoa

By Yinka Adegoke

Quartz Africa, July 4, 2018

http://tinyurl.com/yac2f8az

Europe has an insatiable appetite for chocolate. Not only is it the world’s biggest

consumer of the sweet treat, it’s also the largest producer and exporter, thanks to a

global market share of 70%.

But while the continent dominates the finished-chocolate goods market, African

countries are collectively the beating heart of that success, by producing and

exporting over two-thirds of global cocoa, chocolate’s raw material. Côte d’Ivoire

alone accounts for third of all cocoa produced in the world.

A white paper by agribusiness data company Gro Intelligence (

http://tinyurl.com/y9t7s47n) delves into the numbers and history of the chocolate

trade and it makes for sober reading from an African perspective. In many ways,

Europe’s grip on the sector is unsurprising given that European companies’

innovations transformed the cocoa trade into the chocolate industry in the first

place.

But what is surprising is how little involvement Africa has had in over 200

years—it’s been a major source of the raw material for most of the second half of

the 20th century. From 1961, when data has been available, to 2016, Africa’s share

of total chocolate exports inched up by a miserly 0.9%.

Africa’s attempts to meaningfully break into the export market is so small that

Europe doesn’t even consider it as “competition.” Europe’s biggest rival comes in the

form of Asia, where Indonesia, in particular, has been growing cocoa and building an

industry which taps into the fast-growing middle class of China. Despite Chinese

taste for chocolate growing slowly, the country is already the world’s 11th largest

chocolate market.

Despite this all, Africa is still where the biggest untapped opportunity remains for

production, export, and consumption.

Indonesia can’t expand its cocoa production much more than it has, what with cocoa

being a labor intensive crop (at least it is today). In tandem, labor costs in Asia

are rising. More importantly, as we’ve written here, local entrepreneurs and the

governments of Africa’s largest producers Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana, are getting

serious about the opportunity to move higher up the cocoa-to-chocolate value supply

chain. Indeed, if African countries like Ghana,Côte d’Ivoire, Cameroon, and Nigeria

were to move further up the value chain, they’d reduce a bit of their exposure to the

vagaries of commodity prices.

And as chocolate has traditionally been a fixture of middle class tastes around the

world, it’s unlikely Africa’s still small, but fast-growing, middle classes will be

that different. They might just enjoy their own locally-produced products.

As Gro Intelligence analysts note: “If African governments are serious about

diversifying their economies and providing higher-paying manufacturing jobs to their

people, chocolate production is an obvious industry to pursue. The perfect conditions

exist for chocolate producers to take root.”

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication providing reposted

commentary and analysis on African issues, with a particular focus on U.S. and

international policies. AfricaFocus Bulletin is edited by William Minter.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please write to this

address to suggest material for inclusion. For more information about reposted

material, please contact directly the original source mentioned. For a full archive

and other resources, see http://www.africafocus.org

|