|

Algeria

Angola

Benin

Botswana

Burkina Faso

Burundi

Cameroon

Cape Verde

Central Afr. Rep.

Chad

Comoros

Congo (Brazzaville)

Congo (Kinshasa)

Côte d'Ivoire

Djibouti

Egypt

Equatorial Guinea

Eritrea

Ethiopia

Gabon

Gambia

Ghana

Guinea

Guinea-Bissau

Kenya

Lesotho

Liberia

Libya

Madagascar

Malawi

Mali

Mauritania

Mauritius

Morocco

Mozambique

Namibia

Niger

Nigeria

Rwanda

São Tomé

Senegal

Seychelles

Sierra Leone

Somalia

South Africa

South Sudan

Sudan

Swaziland

Tanzania

Togo

Tunisia

Uganda

Western Sahara

Zambia

Zimbabwe

|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

Africa/Global: Drug Company Profits vs. Public Health

AfricaFocus Bulletin

October 16, 2018 (181016)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

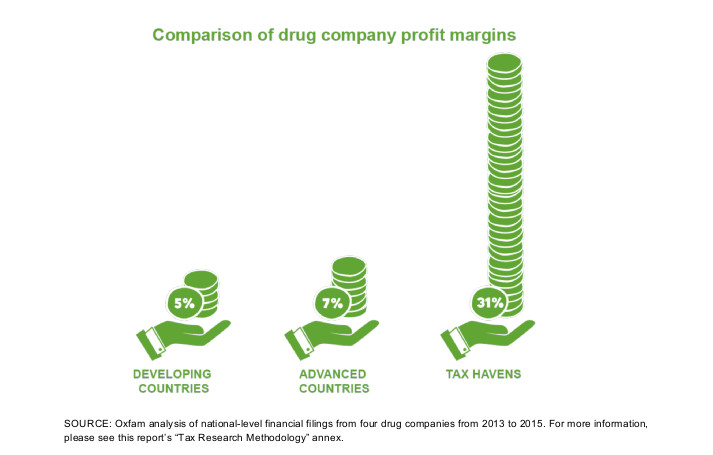

"Oxfam examined publicly available data on subsidiaries of four of the largest US

drug companies and found a striking pattern. In the countries analyzed that have

standard corporate tax rates, rich or poor, the corporations’ pretax profits were

low. In eight advanced economies, drug company profits averaged 7 percent, while in

seven developing countries they averaged 5 percent. Yet globally, these corporations

reported annual global profits of up to 30 percent. So where were the high profits?

Tax havens. In four countries that charge low or no corporate tax rates, these

companies posted skyrocketing 31 percent profit margins." - Oxfam, September 2018

Giant pharmaceutical companies are hardly unique in finding ways to maximize

profits by avoiding taxes. But even compared to giant corporations in other

industries, they are strikingly successful in such efforts. They are also exceptional

in the extravagance of their claims to benefit the public by innovative medical

research, while resisting efforts to make those medical advances available to all who

need them.

Oxfam's report analyzing this contrast is not comprehensive. But it includes four

of the ten largest pharaceutical companies with worldwide scope: Pfizer (largest

pharmaceutical company worldwide), Johnson & Johnson (#4), Merck (#5), and Abbott

(#7), according to http://www.pharmexec.com/pharm-execs-top-50-companies-2018.

The separate subsidiaries of the four companies examined by the Oxfam research

team were limited to those for which public information on revenue and profits was

available, including 844 subsidiaries in four tax havens (Belgium, Ireland,

Netherlands, and Singapore), 53 subsidiaries in 7 different developing countries

(Chile, Columbia, Ecuador, India, Pakistan, Peru, and Thailand), and 222 subsidiaries

in 8 advanced industrial countries (Australia, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, New

Zealand, Spain, and UK).

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on health, visit

http://www.africafocus.org/intro-health.php For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on

tax dodging and related issues, visit http://www.africafocus.org/intro-iff.php

For more background information on campaign to lower the price of new drugs,

highly successful to date in cases such as basic HIV/AIDS treatment and ongoing for

new drugs for drug-resistant TB, cancer, and other diseases, see the Doctors without

Borders Access Campaign website

(https://msfaccess.org/)

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

AfricaFocus Publication Break

AfricaFocus Bulletin will be taking a break from publication until after the

November 6 U.S. midterm elections. Like many other U.S. citizens, I am planning to

put as much time and energy as possible into helping elect progressive candidates at

all levels. This will include passing on relevant action opportunities for others

making the same commitment through my personal networks and through my public-facing

Facebook pages for

AfricaFocus and other issues (Intersections).

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

Prescription for Poverty : Drug companies as tax dodgers, price gougers, and

influence peddlers

September 2018

Oxfam

https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/prescription-poverty

Executive summary

The world’s biggest drug companies are putting poor people’s health at risk by

depriving governments of billions of dollars in taxes that could be used to invest in

health care, and by using their power and influence to torpedo attempts to bring down

drug costs and police their behavior.

New Oxfam research shows that four major pharmaceutical firms—Abbott, Johnson

& Johnson, Merck, and Pfizer—systematically stash their profits in overseas tax

havens. As a result, these four corporate giants appear to deprive the United States

of $2.3 billion annually and deny other advanced economies of $1.4 billion. And they

appear to deprive the cash-strapped governments of developing countries of an

estimated $112 million every year—money that could be spent on vaccines, midwives, or

rural clinics.

Such tax dodging corrodes the ability of governments everywhere to provide the

public services that are essential to reducing poverty and that are particularly

important for women. And it weakens governments’ ability to invest in health

research, which has proven to be fundamental to medical breakthroughs.

As if this weren’t enough, the corporations mount massive lobbying operations to

give price gouging and tax dodging a veneer of legitimacy. Their influence peddling

is most blatant in the United States, where the pharmaceutical industry outspends all

others on lobbying. But it is equally pernicious in developing countries, where the

companies have won sweetheart deals that lower their taxes and divert scarce public

health dollars to pay for their high-priced products—and where they deploy the clout

of the US government to protect their profits.

Tax dodging by pharmaceutical companies is enriching wealthy shareholders and

company executives at the expense of us all—with the highest price paid by poor women

and girls. Oxfam is not accusing the drug companies of doing anything illegal.

Rather, this report exposes how corporations can use sophisticated tax planning to

take advantage of a broken system that allows multinational corporations from many

different industries to get away with avoiding taxes.

When funding is cut, families lose medical care or are driven further into poverty

by health care debts. When health systems crumble, women and girls step into the

breach to provide unpaid care for their loved ones—compromising their own health and

their prospects for education and employment. When governments are deprived of

corporate tax revenues, they often seek to balance the budget by raising consumption

taxes, which tend to take a larger bite out of poor women’s incomes.

Corporations should be more transparent about where they earn their money, they

should pay tax in alignment with actual economic activity, rather than abusing tax

havens, and they should use their political influence responsibly, rather than

undermining governments’ efforts to provide medicines, schools, and roads for us all.

Tax dodging

Oxfam examined publicly available data on subsidiaries of four of the largest US

drug companies and found a striking pattern. In the countries analyzed that have

standard corporate tax rates, rich or poor, the corporations’ pretax profits were

low. In eight advanced economies, drug company profits averaged 7 percent, while in

seven developing countries they averaged 5 percent. Yet globally, these corporations

reported annual global profits of up to 30 percent. So where were the high profits?

Tax havens. In four countries that charge low or no corporate tax rates, these

companies posted skyrocketing 31 percent profit margins.

While the information is far from complete, the pattern is consistent: this is

either an astounding coincidence or the result of using accounting tricks to

deliberately shift profits from where they are actually earned to tax havens. Pfizer,

Merck, and Abbott are among the 20 US corporations with the greatest number of

subsidiaries in tax havens; Johnson & Johnson is not far behind. All four were

among the US corporations with the most money stashed overseas: at the end of 2016,

these four companies alone held an astounding $352 billion offshore.

Profits can vary from country to country for any number of reasons, aside from the

deliberate shifting of profits to avoid tax. Corporations may have higher

transportation costs in some markets, for example, or employ more people. But it is

highly unlikely that these explanations can fully account for the consistent pattern

of much higher profits being posted in countries with very low tax rates where these

corporations do not sell the majority of their medicines.

Pharma corporations’ “profit-shifting” may take the form of “domiciling” a patent

or rights to its brand not where the drug was actually developed or where the firm is

headquartered, but in a tax haven, where a company’s presence may be as little as a

mailbox. That tax haven subsidiary then charges hefty licensing fees to subsidiaries

in other countries. The fees are a tax-deductible expense in the jurisdictions where

taxes are standard, while the fee income accrues to the subsidiary in the tax haven,

where it is taxed lightly or not at all. Loans from tax-haven subsidiaries and fees

for their “services” are other common strategies to avoid taxes.

Recent research by tax economist Gabriel Zucman estimates that nearly 40 percent

of all corporate profits were artificially shifted to tax havens in 2015—one of the

major drivers of declining corporate tax payments worldwide.

Drug companies are masters at taking advantage of the global “race to the bottom”

on tax. Both corporations and governments are to blame. A dysfunctional international

tax system allows multinational companies to artificially shift their profits away

from where they sell and produce their products to low-tax jurisdictions. Companies

are only too glad to take advantage of the broken system—and to invest millions in

lobbying to further tilt the playing field in their favor.

..........

More transparency would shed light on how unjust the current system is. None of

the four drug companies publish country-by-country reporting (CBCR)—basic financial

information for every country in which they operate, including revenue, profits,

taxes paid, number of employees, and assets.

Nonetheless, it is possible to use the data that is publicly available to estimate

how much tax these companies may be avoiding due to an unequal distribution of

profits. In seven developing countries alone—and just from the small sampling of

subsidiaries Oxfam was able to access—the four companies may have underpaid $112

million in taxes annually between 2013 and 2015, which is more than half of what they

actually paid. Johnson & Johnson may have underpaid $55 million in taxes every

year; Pfizer, $22 million; Abbott, $30 million; and Merck, $5 million.

........

These amounts are pocket change to these corporate behemoths. But they represent

significant losses to low-income and middle-income countries. Developing countries

could use the money to address the yawning gaps in public health services that keep

many of the poorest people in the world from lifting themselves out of poverty.

The HPV vaccine is one example. Human papilloma virus (HPV) is a sexually

transmitted infection that can cause cervical cancer, the fourth-most-common cancer

among women worldwide and the second-most-common cancer in women living in less

developed regions. HPV kills 300,000 people every year; every two minutes a life is

lost to this disease, and nine out of 10 of these deaths are women in low- and

middle-income countries. For example, in India, 67,477 women died of cervical cancer

in 2012. The HPV vaccine drastically reduces the incidences of HPV and cervical

cancer.

The amount of money we estimate these companies may have avoided in tax is enough

to buy vaccines for more than 10 million girls, about two-thirds of the girls born in

2016 in the seven developing countries Oxfam examined. India could buy HPV vaccines

for 8.1 million girls, which is 65 percent of the girls born in 2016. In Thailand,

where 4,500 women die each year from cervical cancer, the $18.65 million in taxes we

estimate these companies underpaid per year would be enough to pay for HPV vaccines

for more than 775,000 girls, more than double the number born in 2016.

One might think that pharmaceutical profits really are lower in poorer countries,

where purchasing power is small and drugs are sold at a discount. But the data

indicates a different story. In advanced economies with larger markets and ample

purchasing power, the drug companies’ profit margins are just as slim as in

developing countries. The corporations may have avoided even more in taxes in these

larger markets, a total of nearly $3.7 billion annually—equivalent to two-thirds of

the $5 billion they actually paid. Johnson & Johnson led the pack with an

estimated $1.7 billion underpaid annually. Pfizer may have underpaid by $1.1 billion,

Merck $739 million, and Abbott $169 million.

Profits and innovation

Tax dodging, high prices, and influence peddling help explain the extreme

profitability of these companies—and the extreme benefits they offer their wealthy

shareholders and senior executives. The 25 largest US drug companies had global

annual average profit margins of between 15 and 20 percent in the period 2006–2015;

the figure for comparable nondrug companies was 4 to 9 percent. 27 These high

profits, in turn, increase the incentive that these corporations have to shift

profits and avoid tax.

The current system for biomedical research and development (R&D), a

cornerstone of these corporations’ business model, is based on monopoly protection

secured by intellectual property rules as pharmaceutical companies invest in

development of products that can produce the highest profit. The IP-based system of

R&D has failed to produce many medicines needed for public health. For example,

there has been no new class of antibiotics developed since 1987 despite the rising

problem of antimicrobial resistance. 28

The companies claim they need superprofits so they can invest in discovering new

medicines to treat the world’s ailments, but this simply isn’t true. Big drug

companies spend more on whopping payouts to shareholders and executives than on

research and development. In the decade from 2006 to 2015, they spent $341.4 billion

of their $1.8 trillion in revenue on stock buybacks and dividends—equivalent to 19

percent. They spent $259.4 billion on R&D, or only 14 percent. What’s more,

R&D expenses are tax deductible.

The cost of medicines, many of which were originally set at exorbitant prices, has

continued to rise dramatically, with seven of the nine best-selling drugs sold by

Pfizer, Merck, and Johnson & Johnson seeing double-digit price increases in

2017.0 For example, Pfizer raised the price of Lyrica—which treats diabetic nerve

pain, has no generic competition, and generated $4.5 billion for the company in sales

last year—by more than 29 percent in 2017.

In July the South African government negotiated a reduction in price to $400 for a

six-month course for bedaquiline (see

http://tinyurl.com/y8d3cxqt).

But that is still far greater than the estimated

potential price for a generic equivalent.

New medicines are also set at sky-high prices from the start. Take, for example,

Ibrance, a drug for metastatic breast cancer, which Pfizer put on the market for

nearly $10,000 per month. These high prices are unaffordable in the US, where medical

costs are the primary reason for individual bankruptcy. In low- and middle-income

countries, such outrageous prices break public health budgets and place the burden of

paying on sick people and their families, who cannot afford it. As another example, a

new medicine to treat multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, bedaquiline, was priced by

Janssen—a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson in South Africa—at $820 for the six-

month course, which makes it unaffordable for most who need it, especially galling

when researchers estimate a generic equivalent of the medicine could be made

available for only $48.

In recognition of the global nature of this crisis in access to medicines, the UN

Secretary-General set up a High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines that produced a

report containing important recommendations to ensure innovation and access to

medicines. Oxfam has called on governments and international health organizations to

fully implement the recommendations of the High-Level Panel.

Even while Pfizer hiked the price of dozens of drugs, the total compensation of

Pfizer’s CEO leaped up by 61 percent in 2017, to $26.2 million. That year Johnson

& Johnson’s CEO earned $22.8 million, Merck’s earned $17.1 million, and Abbott’s

earned $15.6 million. The average compensation for a drug company CEO in 2015 was

$18.5 million, 71 percent greater than the median earned by executives in all

industries.

The companies’ R&D spending is also smaller than the billions they spend on

marketing. In 2013, Johnson & Johnson spent more than twice as much on sales and

marketing than on R&D ($17.5 billion vs. $8.2 billion). Pfizer nearly did as well

($11.4 billion vs. $6.6 billion), and Merck spent 20 percent more ($9.5 billion vs.

$7.5 billion). These marketing costs are also tax deductible.

The reality is that the taxpayer-funded National Institutes of Health in the

United States is by far the largest investor in health research, with European

governments providing substantial funding, as well. All 210 drugs approved in the

United States between 2010 and 2016 benefited from publicly funded research, either

directly or indirectly. The source for these public investments, of course, is taxes.

Patients thus often pay twice for medicines: through their tax dollars and at the

pharmacy—or three times if we count the extra tax dollars we pay because the

companies don’t.

Corporate social responsibility

Pharmaceutical corporations paint themselves as noble scientists leading the

charge against disease. Pfizer’s code of conduct says: “Integrity is more than just

complying with the law. It is one of our core values.” Johnson & Johnson’s

corporate credo states: “We must be good citizens—support good works and charities

and bear our fair share of taxes.”

Unfortunately, the reality of these corporations’ business practices bears little

resemblance to this rhetoric.

These companies should choose the high road. Rather than engage in elaborate

schemes to hide their profits, they must pay their taxes in an open and transparent

way. After all, the companies’ very profitability depends on publicly funded

research, public drug certification, public procurement, and public protection of

intellectual property.

Governments must do more to reverse their race to the bottom on taxation. They

must mandate basic transparency measures that would prevent abuse by multinationals.

They must also open up budget and spending processes to citizens to ensure that

public spending meets citizen priorities. Oxfam’s Fiscal Accountability for

Inequality Reduction (FAIR) program supports citizen engagement in government

decisions on taxes, budgets, and expenditures, including on health, in dozens of

countries around the world.

Governments must allocate sufficient available public resources to important

social services, and citizens must engage governments to ensure that budget decisions

reflect citizen priorities, including access to affordable health care. Serious

coordinated action is essential if we are to unravel the global web of secrecy that

encourages rich corporations to avoid paying their fair share. Women and men around

the world are standing up and calling for better and fairer tax and health systems,

and we stand shoulder to shoulder with them.

The way forward

Tax dodging, high prices, and influence peddling clearly victimize the most

vulnerable. Abbott, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, and Pfizer funnel superprofits from

people living in poverty to wealthy shareholders and corporate executives, driving

ever wider the gap between the richest and the rest.

As with most drivers of inequality, exorbitant drug prices, aggressive tax

avoidance, and excessive lobbying are not accidental. They result from deliberate

choices made by companies and by the politicians under their sway. It is our hope

that this report will encourage the four companies and others to reform their

policies and practices, and that it will spur governments to enact rules that promote

responsibility and benefit all society. We believe such a change is in the companies’

long-term interest. Just as extreme inequality is toxic for society, undermining

public institutions is no recipe for a stable, profitable industry.

Oxfam’s recommendations

We call on companies to:

Be more transparent by publishing all information necessary for citizens to

understand and assess the company’s tax practices.

- Publish full country-by-country reporting (CBCR) of key financial information.

- Publish a full list of all company subsidiaries in every country where

they operate.

Pay their fair share by aligning tax payments with actual economic activity.

- Publicly commit to pay tax on profits where value is created and economic

activity takes place, and to stop artificially shifting profits to low-tax

jurisdictions.

- Take concrete steps to progressively align economic

activities and tax liabilities, including shutting down subsidiaries in tax havens

when a primary purpose of those subsidiaries is to avoid taxation.

Use their influence responsibly to shape a more equitable tax system for

sustainable and inclusive growth.

- Publicly commit to advocate for greater transparency, for an end to abusive tax

practices, and for stronger international cooperation to stop the dangerous “race

to the bottom” on corporate tax.

- Publicly disclose all contributions

made to political candidates, policymakers, trade associations, think tanks,

coalitions, and other political entities to influence policy in the US and abroad.

- Publicly commit to align the corporations’ financial contributions and

private advocacy with their credos and codes of conduct on tax policy issues.

- Monitor the impact of their policies, pricing, and other practices on

women and girls living in poverty.

Enable access to affordable medicines for all by:

- Publicly declaring actual spending on R&D, production, and marketing of

medicines and committing to full transparency on medicine prices, results of

clinical trials, and patent information.

- Publicly declaring support for

the UN High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines and its recommendations, including

governments’ right to use mechanisms in the World Trade Organization (WTO)

Agreement on Trade- Related Intellectual Property (known as the TRIPS agreement) to

reduce medicine prices, affirming that intellectual property protection must not

take precedence over public health needs.

We call on governments to:

Require companies to adhere to full transparency and pay their fair share of

taxes.

- Mandate and implement public country-by-country financial reporting for all

large multinational corporations.

- Require large multinational

corporations to pay a fair, effective tax rate on their profits, strengthen rules

to discourage profit-shifting, and take action against tax havens.

Ensure access to medicines for their citizens.

- Require corporations to disclose the cost of R&D, production, and marketing

of medicines before approving product registration.

- Implement the

recommendations of the UN High-Level Panel report at the national level and call

for implementation by international institutions including the World Health

Organization (WHO), the WTO, and the UN.

- Invest in public health

services that are free for patients at the point of use.

We call on citizens to:

Join Oxfam to demand that drug companies stop cheating women and girls out of the

chance to beat poverty.

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication providing reposted

commentary and analysis on African issues, with a particular focus on U.S. and

international policies. AfricaFocus Bulletin is edited by William Minter.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at

africafocus@igc.org. Please write to this address to suggest material for

inclusion. For more information about reposted material, please contact directly the

original source mentioned. For a full archive and other resources, see http://www.africafocus.org

|