|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

Africa/Global: Charting Where They Hide the Money, 1

AfricaFocus Bulletin

March 12, 2018 (180312)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

"Switzerland, the United States and the Cayman Islands are the world’s biggest

contributors to financial secrecy, according to the latest edition of the Tax Justice

Network’s Financial Secrecy Index (FSI). ... Kenya, which this year set up its own

tax haven in the form of the Nairobi International Financial Centre, is an example of

how interests of western financial service lobbyists have successfully lured

governments into a race to the bottom. Kenya, which has been assessed for the first

time in the 2018 FSI, has an extremely high secrecy score of 80/100." - Tax Justice

Network

The FSI for 2018, released by the Tax Justice Network on January 31, is far more than

a simple index. It is an in-depth survey as well as ranking of the countries most

deeply involved in concealing wealth through offshore financial services. Based on a

quantitative measure of the share of such cross-border financial services based in

each country, and an in-depth qualitative evaluation of national laws and regulations

affecting transparency and secrecy, the FSI provides the indispensable context for

investigative journalism exposes of specific cases and advocacy by civil society

groups at both national and international levels.

In striking contrast to Transparency International "Corruption Perceptions Index

(CPI) (https://www.transparency.org/), which rates countries on the basis of

observers' perceptions of the extent of corruption, the FSI focuses on the mechanisms

which permit the fruits of corruption and other hidden assets to be concealed.

Ironically, Switzerland, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands are ranked as among the

least corrupt on the CPI, but they also lead on the FSI as the best places to hide

the fruits of corruption, tax evasion, and other crimes.

The system that allows this to happen is in fact global, and its distribution by

country, by intention, is hard to track. This two-part AfricaFocus contains

substantive excerpts from the Financial Secrecy Index reports. This first part (sent

out by email and available on-line at http://www.africafocus.org/docs18/fsi1803a.php)

excerpts overview analyses from the authors covering the global picture and the

African continent. The second part, not sent out by email but available at

http://www.africafocus.org/docs18/fsi1803b.php) , provides excerpts from country

reports on the United Kingdom, the United States, Kenya, Liberia, South Africa, and

Mauritius.

Much more extensive data in narrative, database, and graphic formats, is available at

http://www.financialsecrecyindex.com

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on illicit financial flows, tax evasion, and

related topics, visit

http://www.africafocus.org/intro-iff.php

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

Financial Secrecy Index 2018

Introduction

https://www.financialsecrecyindex.com/

The Financial Secrecy Index ranks jurisdictions according to their secrecy and the

scale of their offshore financial activities. A politically neutral ranking, it is a

tool for understanding global financial secrecy, tax havens or secrecy jurisdictions,

and illicit financial flows or capital flight.

An estimated $21 to $32 trillion of private financial wealth is located, untaxed or

lightly taxed, in secrecy jurisdictions around the world. Secrecy jurisdictions - a

term we often use as an alternative to the more widely used term tax havens - use

secrecy to attract illicit and illegitimate or abusive financial flows.

Illicit cross-border financial flows have been estimated at $1-1.6 trillion per year:

dwarfing the US$135 billion or so in global foreign aid. Since the 1970s African

countries alone have lost over $1 trillion in capital flight, while combined external

debts are less than $200 billion. So Africa is a major net creditor to the world -

but its assets are in the hands of a wealthy élite, protected by offshore secrecy;

while the debts are shouldered by broad African populations.

Yet all rich countries suffer too. For example, European countries like Greece, Italy

and Portugal have been brought to their knees partly by decades of tax evasion and

state looting via offshore secrecy.

A global industry has developed involving the world's biggest banks, law practices,

accounting firms and specialist providers who design and market secretive offshore

structures for their tax- and law-dodging clients. 'Competition' between

jurisdictions to provide secrecy facilities has, particularly since the era of

financial globalisation really took off in the 1980s, become a central feature of

global financial markets.

The problems go far beyond tax. In providing secrecy, the offshore world corrupts and

distorts markets and investments, shaping them in ways that have nothing to do with

efficiency. The secrecy world creates a criminogenic hothouse for multiple evils

including fraud, tax cheating, escape from financial regulations, embezzlement,

insider dealing, bribery, money laundering, and plenty more. It provides multiple

ways for insiders to extract wealth at the expense of societies, creating political

impunity and undermining the healthy 'no taxation without representation' bargain

that has underpinned the growth of accountable modern nation states. Many poorer

countries, deprived of tax and haemorrhaging capital into secrecy jurisdictions, rely

on foreign aid handouts.

This hurts citizens of rich and poor countries alike.

Switzerland, USA and Cayman top the 2018 Financial Secrecy Index

by George Turner

Tax Justice Network, January 30, 2018

https://www.taxjustice.net/2018/01/30/2018fsi/

Switzerland, the United States and the Cayman Islands are the world’s biggest

contributors to financial secrecy, according to the latest edition of the Tax Justice

Network’s Financial Secrecy Index (FSI).

The full financial secrecy index can be found online at

http://www.financialsecrecyindex.com. There you can find interactive tables and maps

of the FSI, as well as download reports on specific countries. A direct link to the

table of rankings by country is at http://tinyurl.com/yblxx27e.

Financial secrecy is a key facilitator of financial crime, and illicit financial

flows including money laundering, corruption and tax evasion. Jurisdictions who fail

to contain it deny citizens elsewhere their human rights and exacerbate global

inequality.

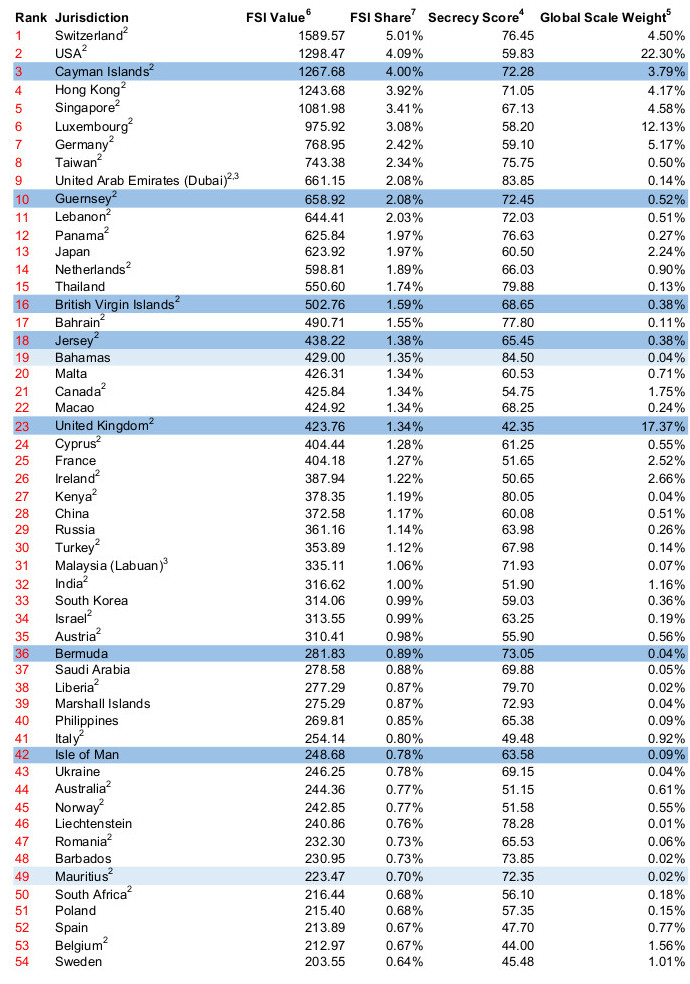

The table below shows the top-ranked 54 countries on the FSI.

The full interactive table is available

here.

Switzerland, the global capital of bank secrecy, retains the worst ranking, and the

US has moved up to second. With Bahrain and Lebanon dropping out of the top ten,

Guernsey and a new entry in Taiwan has replaced them.

The US’ rise in the FSI 2018 rankings is part of a worrying trend. This is the second

time in succession that the USA has risen up the Financial Secrecy Index. In 2013 the

States was in 6th place, and in 2015 it took 3rd. In 2015 the country was one of the

few to increase its secrecy score. This time the increase in ranking is driven by a

huge rise in their share of the market in offshore financial services that wasn’t

neutralised by a significant reduction in their secrecy. In total, the share of

global offshore financial services taken by the United States rose by 14% between the

2015 and 2018 index from 19.6% to 22.3%.

The United States remains a secrecy jurisdiction as it refuses to take part in

international initiatives to share tax information with other countries, and has

failed to end anonymous companies and trusts aggressively marketed by some US states.

There is now real concern about the damage this promotion of illicit financial flows

is doing to the global economy.

Slow progress in the global fight against financial secrecy

The 2015 Index noted several improvements towards global financial transparency

following the 2008 financial crisis and the huge budget deficits that it created,

where governments around the world sought to reign in tax abuse by its citizens, and

by multinational corporations.

Some of those efforts are now starting to bear fruit. Most importantly, countries

have now started to exchange information on bank accounts held by foreign citizens in

their jurisdictions on an automatic basis.

But this Financial Secrecy Index demonstrates how ten years on from the financial

crisis all countries still have a long road ahead of them to improve their

performance on financial secrecy. The most transparent country – Slovenia – has a

secrecy score of 41.8, out of a total possible score of 100. A score of 0 would

represent ideal, competition and market friendly transparency. In other words, if the

Financial Secrecy Index were a school exam, Slovenia (the best student) would have

barely passed, with less than 60% of the correct “transparency” answers. The worst

countries only got close to 10% of the “transparency” questions right (a secrecy

score close to 90). Following this analogy, practically all countries would have to

repeat the school year.

The top two countries in this year’s FSI are the two that have been most resistant to

the key policy of automatic information exchange between tax authorities. The US

refuses to take part altogether. Instead, it has set up its own parallel system

(FATCA) which seeks information on US citizens abroad, but provides little, if any,

data to foreign countries.

The global capital of banking secrecy, Switzerland has delayed the implementation of

automatic information exchange, and in 2017 lawmakers attempted to stop it altogether

with countries they deemed ‘corrupt’. As the FSI demonstrates, countries like

Switzerland are fundamental to the flow of illicit financial funds, such as the

proceeds of corruption. Switzerland’s attempts to stop transparency for funds they

receive from countries with perceived high levels of corruption will simply make

tackling corruption in those countries harder.

After the financial crash further scandals have led to a greater push for more

transparency, such as the demand for public registers of company owners. Yet this

progress has been difficult, as powerful vested interests working with friendly

governments seek to frustrate change. The UK government for example continues to

insist on the right of its satellite tax havens to maintain the secrecy of company

ownership, and the German government, with others, have sought to impede attempts to

make progress on the beneficial ownership issue within the European Union.

Financial secrecy’s impact on human rights

Six out of the Top 10 FSI 2018 countries are either members of the OECD or their

dependencies. Another three are Asian tax havens, demonstrating how major economies

are driving the market for financial secrecy.

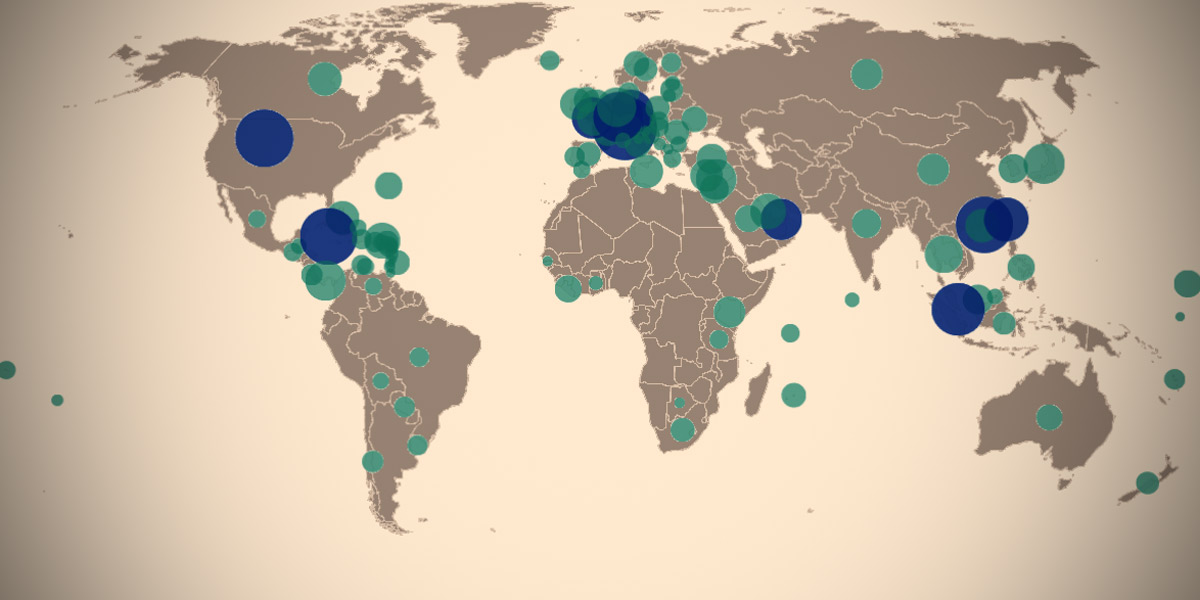

Secrecy jurisdictions are found all over the world.

On this map the top ten are shown in blue. An interactive version

of the map is available here.

Kenya, which this year set up its own tax haven in the form of the Nairobi

International Financial Centre, is an example of how interests of western financial

service lobbyists have successfully lured governments into a race to the bottom.

Kenya, which has been assessed for the first time in the 2018 FSI, has an extremely

high secrecy score of 80/100.

By harboring the ill-gotten gains of kleptocrats and tax evaders, secrecy

jurisdictions deprive governments of the resources needed to provide basic social

protection, and encourage the looting of natural resources.

This impact of financial secrecy on the abuse of human rights is increasingly

recognised globally. Switzerland has been sharply criticised by the United Nations

for the damage that its financial secrecy causes to human rights around the world,

while a recent statement by the UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human

Rights, highlighted the poverty and inequality suffered by citizens of the United

States, in part driven by their government’s desire to become a tax haven. This

statement comes at a time when our index shows the country undermining rights

elsewhere through its promotion of financial secrecy.

How we created the world’s leading study of financial secrecy

The Financial Secrecy Index is the world’s most comprehensive assessment of the

secrecy of financial centres and the impact of that secrecy on global financial

flows. The European Commission’s Joint Research Centre provided methodological

support for the construction of the index. The study is published every two years and

is founded on published, independently verifiable data. In contrast to some so called

‘blacklists’ of tax havens, inclusion in the FSI is not based on political decision

making.

Countries are assessed against criteria which include whether companies, trusts and

foundations are required to reveal their true owners, whether annual accounts are

made available online in open data format, or the extent to which jurisdictions’

rules comply with anti-money laundering standards (FATF’s 40 recommendations).

This year several new indicators have been added to the FSI and existing indicators

have been substantially revised to drill deeper into questions around ownership

registration and disclosure. A total of 20 Key Financial Secrecy Indicators (KFSI) is

used for the measurement of the secrecy score.

In order to create the index, a secrecy score is combined with a figure representing

the size of the offshore financial services industry in each country. This is

expressed as a percentage of global exports of financial services. The bigger player

you are, the more responsibility you have to be transparent.

Beyond of what has been achieved so far by academic or regulatory institutions, the

new FSI is the most comprehensive and rigorous assessment of financial secrecy

worldwide.

New criteria include checking if a jurisdiction provides for

A public register of ownership and annual accounts of limited partnerships (KFSI 5);

A public register of ownership of real estate and a central register of users of

freeports for the storage of high value assets (KFSI 4);

Banking secrecy rules protected by criminal law (risk of prison terms for banking

whistleblowers; KFSI 1);

Public access to tax court verdicts and proceedings, both in criminal and civil tax

matters (KFSI 14);

Mandatory Legal Entity Identifiers for companies created in its territory (KFSI 10);

Harmful tax residency and citizenship rules (KFSI 12);

Public access to unilateral tax rulings and robust local filing requirements for

Country-By-Country Reports (KFSI 9);

Unregistered bearer shares for companies & large banknotes (KFSI 15);

Public statistics on its cross-border financial and economic activities (KFSI 16);

Mandatory reporting obligations of tax avoidance schemes (KFSI 11).

Africa’s battle against financial secrecy: Financial Secrecy Index

by Rachel Etter-Phoya

Tax Justice Network, February 14, 2018

https://www.taxjustice.net/ - direct URL: http://tinyurl.com/yb7s2txa

How are Switzerland, the United States, and the Caymans working against African

efforts to stem the tide of illicit financial flows? They’re among the worst

offenders in the Tax Justice Network’s 2018 Financial Secrecy Index.

The index was launched at the end of January 2018 and weights a country’s secrecy

score against its global share of financial services. This means that countries that

top the rankings have a far higher risk for illicit financial flows running through

their systems than countries that may have a higher level of secrecy, but have much

smaller-scale financial services. 20 key indicators are used to assess secrecy

levels, including banking and tax court secrecy, country-by-country reporting

compliance, ownership disclosure rules, and tax administration capacity.

The problem for Africa

Africa remains a net creditor to the world because of illicit financial flows. These

flows include money from criminal activity and corruption, tax evasion, avoidance and

planning, as well as hidden wealth. So-called foreign aid is dwarfed by the amounts

that are leaving the continent. Sub-Saharan African countries lost over USD 1

trillion in capital flight between the 1970s and 2010; external debt was less than

one-fifth of this. Financial secrecy is the enabler.

The Paradise Papers was a disturbing reminder of the scale of the problem. 13.4

million documents were leaked from Appleby, a leading British offshore law firm, and

Asiaciti, a family-owned trust company, which were investigated by over 90 media

partners with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

We learned that Namibians lost potential tax revenues from its fishery resources

through a complex corporate arrangement that exploited a double tax treaty signed

with Mauritius. Angolans’ sovereign wealth fund was tapped into by a financier who

incorporated companies in secrecy jurisdictions for investment projects in which he

had a stake. And mining giant Glencore’s nefarious practices in the Democratic

Republic of the Congo and in Burkina Faso have also likely reduced the revenue these

governments have to spend on vital public services.

South Africa has also had its fair share of challenges with secrecy jurisdictions.

The notorious Gupta family along with their politically-exposed associates have been

able to hide behind opaque companies to gain questionable access to government

contracts. For example, the family is reported to have used shell companies in the

United Arab Emirates to move ‘the dubious proceeds of state tenders in South Africa

to their collection of shell companies in and around Dubai’. The United Arab Emirates

is ranked number nine in the Financial Secrecy Index 2018, with an ‘”ask-noquestions,

see-no-evil” approach to commercial transactions, financial regulation and

crimes’.

African secrecy jurisdictions on the rise

Financial secrecy has also reared its ugly head on the continent itself. Nine African

countries are included in this year’s Financial Secrecy Index:

Kenya found itself in the top 30 countries worldwide with a very high secrecy score

(80 out of 100). This may not come as a surprise. The country’s Vision 2030 includes

the establishment of the Nairobi International Financial Centre as one of its

commitments. Legislation entered into force in September last year to encourage

foreign direct investment to be channelled through the East African nation to other

countries in the region. Kenya has adopted a model similar to the City of London (the

UK having experienced the Finance Curse phenomenon as a result) and continues to

increase its network of double tax agreements.

Double tax agreements aim to prevent income being taxed twice. Yet a number of

associated risks undermine the collection of tax. The treaties restrict the rights of

states to tax foreign investors and owned companies and often do not include adequate

automatic exchange of information provisions. Multinationals and sometimes domestic

companies may set up an entity in an intermediary country, even when they have no

substantive economic activities, to exploit tax treaties in place. This ‘treaty

shopping’ enables companies and individuals to pay lower taxes in conduit countries

and avoid taxes all together in the countries where activities are taking place.

However, with just 15 tax treaties in force, Kenya has some way to go if it is to

compete with one of Africa’s oldest secrecy jurisdictions, Mauritius. In a bid to

reduce its reliance on sugar back in the 1970s, this island nation started offering

preferential tax terms and exemptions to foreign investors, and similar ones exist

today. The country has entered double tax agreements with 43 nations, 16 of which are

with African states. Zero-percent capital gains tax has lured many companies to set

up shop – with no genuine economic activity – on the island, significantly reducing

their tax burden at the expense of other countries, often not paying capital gains

tax anywhere. South Africa and India have successfully renegotiated their agreements

with Mauritius to be able to collect capital gains and withholding tax. Other African

nations, including Lesotho and Zambia, are following suit and renegotiating treaties.

Ghana toyed with setting up an International Financial Services Centre (IFSC) and

went as far as granting Barclays Bank Ghana Limited an offshore banking licence in

the early 2000s although President John Atta Mills revoked the licence in 2011 to

avoid OECD blacklisting. Worringly, it appears the country has plans to revive the

IFSC.

Much more can be said about secrecy on the continent. We have prepared narrative

reports for eight of the nine African countries included in the Index. Take a look

here. Our partner Tax Justice Network Africa also has a blog series on financial

secrecy. Part 1 is available here.

Global solutions

Some changes have been made to the global infrastructure to tackle secrecy since TJN

launched the first Index in 2009. For example, the OECD is mandated by the G20 to

roll out the automatic exchange of information on taxation, but coverage is patchy

and some countries, particularly African ones, are missing from the arrangement.

Reform is needed now. Besides individual countries addressing laws and regulations to

improve transparency, TJN has identified three major policy responses considering the

latest Financial Secrecy Index:

- Take counter-measures against tax haven USA: the USA ranks second in the Index

this year because it has not improved transparency while other countries have acted.

The global scale of its financial services has also increased. The USA needs to make

it illegal to establish anonymous companies within its borders and it must comply

with the standard for automatic exchange of tax information. We have a policy

proposal for how to incentive the USA, here.

- Adopt the Tax Justice Network’s ABCs of tax transparency: all countries must be

included in the Automatic exchange of information and aggregate statistics published,

all entities must disclose their Beneficial owners and data should be online, free

and in open data format for companies, trusts and foundations, and all multinational

companies must comply with public Country-by-country reporting.

- Introduce a UN global convention on tax transparency: ambitious standards should

be set, with the ABCs of tax transparency at a minimum, through a global, inclusive

process that outlines meaningful sanctions for non-cooperation.

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication providing reposted

commentary and analysis on African issues, with a particular focus on U.S. and

international policies. AfricaFocus Bulletin is edited by William Minter.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please write to this

address to suggest material for inclusion. For more information about reposted

material, please contact directly the original source mentioned. For a full archive

and other resources, see http://www.africafocus.org

|