|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

Africa/Global: Professionals Enabling Corruption

AfricaFocus Bulletin

October 1, 2018 (181001)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

"Lifting the veil of corporate secrecy reveals a simple principle: Offshore is

actually a set of professional services that specialize in enabling businesses and

individuals to effectively retreat from legal, regulatory, and public scrutiny,

empowering them vis-a-vis those who have remained 'onshore' without access to such

services." - Hudson Institute

The image of "tax havens" and the term "offshore" may evoke islands such as Jersey in

the channel between Great Britain and France, the Cayman Islands in the Caribbean, or

Cyprus, which served as a intermediary between the Ukraine and Paul Manafort's

extravagant purchases in the United States. But, as this new report from the Hudson

Institute explains clearly, the system is in fact "without borders," with money from

the global rich, including authoritarian leaders, parked in many places, including

the City of London, Delaware, and New York.

This AfricaFocus contains excerpts from the report on "The Enablers," which is also

available on the Hudson Institute website. Highlighting particularly the flow of

money from authoritarian states to the United States, it spells out the role played

by legal services, incorporation services, financial services, real estate services,

lobbying and public relations services, fintech and cryptocurrency.

There are abundant other sources documenting this system, which is a fundamental

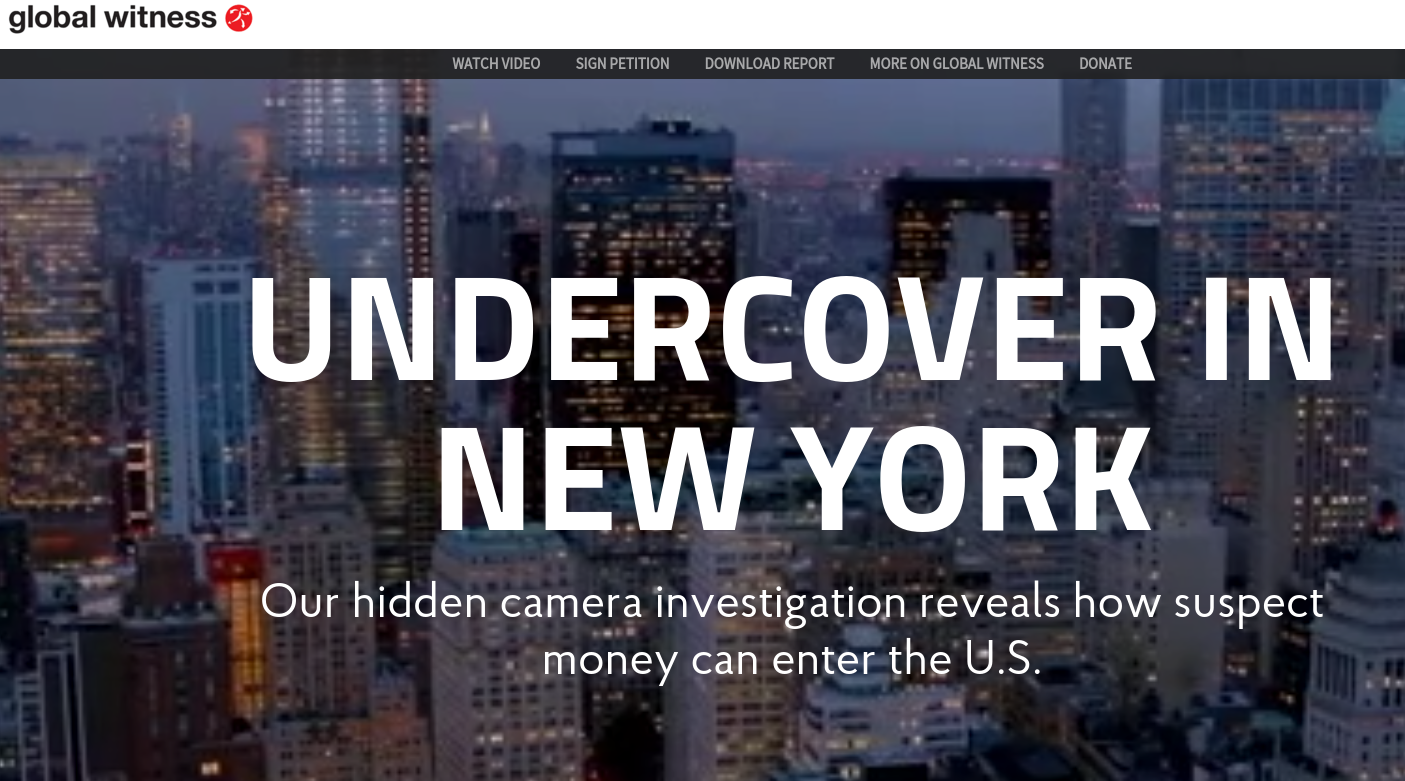

component of today's globalized economy. On legal services, particularly of interest

is the 2016 investigation by Global Witness, in which investigators went under cover

to ask New York lawyers had to hide funds, posing as representatives of an anonymous

African government official (Global Witness, Lowering the Bar;

https://www.globalwitness.org/shadyinc/)

For background on groups campaigning to change this system in the United States, see

The Financial Accountability and Corporate Transparency (FACT) Coalition

(https://thefactcoalition.org/).

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on corruption and illicit financial flows, visit

http://www.africafocus.org/intro-iff.php

Other background resources include:

Top 10 books on illicit financial flows, tax justice, and africa

http://www.africafocus.org/iff-books.php

Resources on the Stop the Bleeding Africa campaign

https://usafricanetwork.org/home/issues/stop-the-bleeding-africa/

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

The Enablers: How Western Professionals Import Corruption and Strengthen

Authoritarianism

Ben Judah, Research Fellow & Nate Sibley, Program Manager, Kleptocracy Initiative

September 2018

http://www.hudson.org

Excerpts only: An audio file of a discussion on this report, and a link to the full

report, is available at http://tinyurl.com/y8re74a5

Introduction

Globalization is playing out unexpectedly as governments, businesses, and individuals

around the world are connected to one another at an unprecedented rate. These new

connections were at first widely hailed as enhancing the influence of the United

States, but their true political consequences are only just beginning to become

clear.

One of the most important but overlooked dynamics, given its national security

implications, has been the pervasive networking of American professional services

providers with power brokers and their acolytes from corrupt authoritarian states.

Certain elements within the legal, financial, and influence communities, seeking new

markets, clients, and profits among an emerging global class of super wealthy actors

with fortunes of dubious provenance, have in the past fifteen years begun offering

their services to transnational kleptocrats linked to authoritarian regimes. From

Washington lobbyists with Kremlin-linked accounts to New York law firms with Chinese

Communist apparatchik clients, these tie-ups have a detrimental effect on the

political and the financial workings of American democracy—one that is only growing.

This report argues that these professionals have become enablers of authoritarian

influence within democracies in a twofold manner. First, they are facilitating the

concealment, insertion, and deployment of kleptocrats’ illicit funds within Western

economies. Second, they are using their skills and expertise to help kleptocrats

establish networks of influence inside democratic societies. This relationship

between Western professionals and authoritarian elites has not only fueled a boom in

money laundering; it has transformed significant elements of the most distinguished,

influential professions into wholesale importers of transnational corruption.

The Emergence of Offshore and the Rise of the Enablers

Before we try to understand the enablers, we need to understand the system in which

they thrive. For Western professionals, facilitating the finances of hostile powers

is nothing new. They have always overseen the offshore financial dealings of hostile

powers, particularly since the rise of the Eurodollar and the Eurobond in the 1960s,

to a significant extent on the back of Soviet funds and as a result of the

disintegration of the Bretton Woods system.

Since the end of the Cold War, however, the tempo has shifted. The dismantling of

totalitarian regimes across Eurasia allowed their elites to become individual

financial actors for the first time. This dovetailed with an aggressive expansion of

American professional services into these territories. Whereas in the 1960s it was

the Soviet state seeking Eurodollars, by the late 1990s, any Eurasian power brokers

worth their salt were personally seeking access to Western professional services.

The consequences of this access to the globalized economy have arguably been vastly

more empowering to political actors hostile to the United States than any other

development of the late 20th century.

But why? Since the Bretton Woods system collapsed, one financial trend has been

constant: the aggressive expansion of a shadow financial system referred to

collectively as “offshore.” On the surface, this is a fiendishly complex interlocking

web of anonymously owned companies and accounts, legally located in secretive

jurisdictions that allow them to circumvent the regulatory and taxation systems of

conventional jurisdictions. Yet lifting the veil of corporate secrecy reveals a

simple principle: Offshore is actually a set of professional services that specialize

in enabling businesses and individuals to effectively retreat from legal, regulatory,

and public scrutiny, empowering them vis-a-vis those who have remained “onshore”

without access to such services. This system is how a business run, staffed,

operating, and earning its profits in the United States can claim that it is in fact

located in another country altogether, despite having no physical presence there.

“Globalization and financial deregulation have led to the ballooning of offshore

finance,” said Gabriel Zucman, assistant professor of economics at UC Berkeley.

“Changes in cultural norms have also played a role: before the 1980s, for instance,

not all corporate executives thought that it was their fiduciary duty to avoid

corporate income taxes by all possible means (e.g., by shifting profits to places

like Bermuda). Today they almost all do.”

Profit margins provide ample explanation for the motivation to escape taxation but

tell us little about the shape and scale of the system itself. This has been driven

by targeted innovation in the legal and financial communities, empowered in the

commanding heights of both the state and the private sector itself, which equated the

dismantling of regulatory frameworks with automatically encouraging growth. This

process was powered by new technologies that permit instantaneous transactions and

emerging forms of secrecy, encryption, and concealment.

The offshore system has turned Western professional services providers into partners

for non-Western authoritarian elites and brought the latter into the Western

financial system. “There are both ethical problems in the finance industry,” says

Zucman, “and a collective intellectual failure at regulating tax havens and

globalization.” Instead, perks set up to profit Western corporations have become

sources of unprecedented power for kleptocrats.

These powers—the power to generate, store, and deploy wealth in different countries,

and the power of anonymity, which enables personal connections to that same wealth to

vanish without a trace—are the common threads stitching together various global

political trends. The increasing capacity of Russia, China, and even the Gulf States

to interfere in Western political systems, and the eruption of protest movements in

countries as varied as Malaysia, Ukraine, Libya, Egypt, and Pakistan, are all fueled

by the power that the offshore system has bestowed upon authoritarian elites—and how

they have played, abused, or mismanaged their hand. Money may not explain

everything—but it does explain rather a lot.

Given the vast figures involved, it is often tempting to discuss global financial

flows from a systemic point of view. However, zooming in, we realize that no

individual transactions—and especially no illicit ones—happen without a helping human

hand. Taking this view enables us to better understand the role played by

professionals within Western legal, financial, incorporation, and real estate

communities who have become systemic enablers of transnational kleptocracy. The boom

in global money laundering that continues to empower authoritarian kleptocrats and

fuel their growing influence would not be possible without them. Studying the

intersection of Western professionals with these kleptocrats is essential to

understanding this trend in modern power.

The Enablers' System

Thanks to a surge in investigative reporting and academic studies, the pattern by

which kleptocrats typically operate in the United States and other democracies has

been clearly established in recent years.

First, a kleptocrat will engage legal and incorporation service providers to place

illicit funds into the legal economy and conceal their origins. Second, financial and

real estate professionals are used to integrate the funds into the mainstream U.S.

economy. Third, lobbying and public relations specialists can suppress scrutiny of

the kleptocrats, whitewash their criminal past, and extend their political reach.

This well-trodden path has emerged from two systemic failings: an outdated and

inadequate anti-money laundering (AML) system, and the failure of ethical standards

and self-regulation within the professions themselves.

Regulators are also paying increased attention to this pattern and the critical role

played by Western professionals within it. The Financial Action Task Force, the

global anti-money laundering watchdog, published a report with the Egmont Group in

July 2018 concerning the role of “professional intermediaries” in concealing

beneficial ownership of legal entities. In 100 case studies from 34 jurisdictions,

“approximately half of all intermediaries involved were assessed as having been

complicit in their involvement,” rather than simply “unwitting or negligent.” In June

2018, the U.S. Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN)

published extensive guidance on the use of “financial facilitators” by corrupt

foreign officials, exploring how these facilitators enable the officials to “access

the U.S. and international financial system to move or hide illicit proceeds, evade

U.S. and global sanctions, or otherwise engage in illegal activity, including related

human rights abuses.”

Legal Services

The first port of call for any kleptocrat seeking to benefit from this system is

contact with the legal community. A lawyer is utterly essential, both to enter the

offshore world and then to exploit its complex landscape, which cannot be navigated

by anyone legally blind. From there, lawyers typically engage incorporation agents

(if they cannot provide the service of company formation themselves) before managing

the kleptocrats’ offshore affairs. This includes providing introductions to the

financial community, specific investment opportunities such as real estate, and even

political opportunities such as contacts with lobbying or public affairs

professionals.

Anti-corruption groups allege that the practice has become widespread within the

American legal community. This was brought sharply to light in 2016, when twelve out

of thirteen law firms approached by an undercover investigator for Global Witness

were willing to discuss ways for an African kleptocrat to move money into the United

States. ...

Unscrupulous lawyers have become the primary accomplices of transnational

kleptocrats. This is abundantly clear from the trickle of kleptocrats who have been

brought to justice in the United States. In recent cases prosecuted by the

Kleptocracy Asset Recovery Initiative of the Department of Justice, in which members

of the American legal community played a key enabling role, the defendants included

Pavlo Lazarenko, former Ukrainian prime minister; Chen Shui-bian, former president of

Taiwan; and Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue, current vice president of Equatorial

Guinea. Legal services were their primary guides.

The legal community’s services to kleptocrats sometimes extend far beyond advising

them on their rights or conducting litigation. They often include business and

investment advice; handling illicit funds in their clients’ trust accounts; setting

up corporate entities or handling interactions with incorporation agents on their

behalf; and introducing them to other professionals in the financial, lobbying, and

public relations communities.

The prevalence of such activities stems from lawyers’ longstanding omission from the

extensive—if often ineffective—AML requirements, which are based on affirmative

reporting. This means that lawyers are not required to screen their clients or file

suspicious activity reports in the same way, for example, as financial institutions—

though they often handle substantial client funds. In fact, attorney-client privilege

can be asserted to protect information about the sources of customer funds pooled in

Interest on Lawyers Trust Accounts (IOLTAs). Up to $400 billion runs through IOLTAs

each year, almost all of it for entirely legitimate and productive reasons—but the

anonymity they afford has also made them ripe for abuse by all manner of financial

criminals, including kleptocrats.3

The role of the legal community in facilitating transnational kleptocracy needs to be

reassessed. Cases in which kleptocrats have been caught and prosecuted in the United

States show that American legal professionals operate not merely as enablers, but

also as force multipliers for kleptocrats’ economic and political influence within

democratic societies. A dangerous minority of legal professionals has been abusing

important legal protections—such as attorney-client privilege—in order to use them as

cover for illicit activity.

These practices have made the legal community an importer of weaponized corruption

into the United States. Once illicit funds have been laundered into the U.S. economy,

they are not just stashed in luxury real estate. They also have the potential to be

deployed in the service of bad actors—including to further the geopolitical ambitions

of adversarial states like Russia.

This has brought the legal profession in for intense criticism from activists

campaigning against authoritarian kleptocracy across the world. “When you look at

Russian government–connected crime,” said Bill Browder, the leading anti-Putin

campaigner, “even more insidious than the actual Russian criminals are the Western

lawyers who are letting them cover up their crimes. These people weren’t brought up

in the live-or-die criminal underworld of Russia but went to the same schools as us

and should know better.” What is strange is that, on the face of it, none of this

should be happening. On paper, the legal community in the United States holds itself

to the highest ethical standards. The American Bar Association’s Model Code for

Professional Responsibility goes as far as to say in its preamble: “Lawyers, as

guardians of the law, play a vital role in the preservation of society. The

fulfilment of this role requires an understanding by lawyers of their relationship

with and function in our legal system. A consequent obligation of lawyers is to

maintain the highest standards of ethical conduct.”

However, even the most casual look at the networking between the legal community and

authoritarians shows that the profession is falling short of these standards and

neglecting its role. “For years now the ABA has been downplaying the role of lawyers

in money-laundering misconduct, claiming that voluntary anti-money laundering efforts

are sufficient when it’s clear lawyers, like banks, should operate under mandatory

AML requirements,” said Elise Bean, a former staff director of the U.S. Senate

Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, who conducted multiple money-laundering

investigations.

...

Policy Recommendations

- Congress should pass legislation requiring legal services providers to perform

reasonable due diligence on prospective foreign clients.

- Given the potential for abuse of attorney-client privilege, Congress should

consider whether legal firms should continue to be able to combine business,

lobbying, legal, and other functions.

- Congress should also consider whether IOLTA accounts should be subject to the same

anti-money laundering regulations as other financial products.

Incorporation Services

Though authoritarian kleptocracies differ from each other in their nature and in the

quantity of funds they bring into the Western financial system, investigators from

U.S. law enforcement are quick to point out that almost without exception, when they

enter this system, they make use of anonymous shell companies. “We consistently see

bad actors using these entities to disguise the ownership of the dirty money derived

from criminal conduct,” Kendall Day, then acting deputy assistant attorney general of

the Justice Department’s Criminal Division, told a Congressional hearing in January

2018.

Anonymous shell companies differ from other money-laundering vehicles such as “front”

companies in that they are legal entities that grant the rights and privileges of a

company to the owner without obligating the owner to perform any of the activities

typically associated with a company. Usually they are deployed within a vast, complex

network of other such companies that are legally located across multiple

jurisdictions. This renders the true identity of the beneficiaries almost impossible

to determine without heavy mobilization of resources, and it is why anonymous shell

companies have been dubbed “weapons of mass corruption” by anti-corruption

campaigners.

The United States is currently the leading mass-producer of anonymous shell

companies, generating 10 times more than 41 other jurisdictions identified as

financial secrecy havens combined. Though some states require more information than

others when a company is incorporated, none require full disclosure of the beneficial

owners who ultimately control it. With a few exceptions—most notably Delaware, which

now supports the collection of beneficial ownership information by the U.S.

Treasury—a race to the bottom between some U.S. states is underway, as they become

increasingly dependent on revenue generated by registration fees. The result is that

it currently takes more information to obtain a library card in the U.S. than to

create an anonymous shell company, a situation unmatched anywhere in the world except

Kenya. “The rest of the world is starting to crack down on secret and illicit finance

while the United States continues to play banker to the world’s authoritarian

kleptocrats,” said Gary Kalman, executive director of the Financial Accountability

and Corporate Transparency Coalition.

Researcher Anat Admati calls this “a crisis of the corporate form.” The American

company, historically intensely guarded, has become in her eyes bastardized,

transformed into a tool that permits those with the resources to exploit it to evade

financial liability and act with criminal impunity. This interpretation was largely

validated by the 2014 Global Shell Games study, in which researchers approached

incorporation agents for assistance in setting up anonymous shell companies while

posing as money launderers, corrupt officials, and terrorist financiers. Despite the

suspicious nature of their inquiries, it was incorporation agents based in the United

States who proved the most willing to help and least anxious to ask questions—putting

the U.S. behind traditional financial secrecy havens like the Cayman Islands, St.

Kitts and Nevis, or the British Virgin Islands.

This state of affairs has led to widescale abuse of U.S. company incorporation, not

only by kleptocrats from countries as diverse as Ukraine, Malaysia, and Equatorial

Guinea, but also by terrorist groups such as Hezbollah and hostile regimes such as

Venezuela and Iran. In fact, Iran somehow managed to purchase and lease out an

entire skyscraper on New York’s Fifth Avenue for 20 years without detection. The

confluence of two factors has permitted this transformation in the use of American

companies. One is the incorporation sector’s omission from affirmative AML reporting

requirements. The other is a powerful coalition of state and professional lobbies

that resist the imposition of even a non-public beneficial ownership register

available only to law enforcement—though this opposition is dwindling as the national

security arguments in favor of such a register become more widely accepted.

Policy Recommendations

- Congress should mandate the creation of a federally overseen register of beneficial

ownership for companies and trusts.

- Incorporation agents should be legally required to perform reasonable due diligence

on prospective clients.

- Penalties should be introduced for failure to carry out reasonable due diligence

and/or for intentionally submitting misleading information to the beneficial

ownership register.

Financial Services

Law enforcement breaks down money laundering into three stages: placement (moving

illicit funds into the financial system), layering (concealing their origin), and

integration (using the successfully laundered funds for purchases and investments).

Whereas the legal community is essential for the placement and layering of

kleptocrats’ illicit funds, financial services providers can be engaged to assist

with integration. This is the point at which funds are set to work—accumulating value

if securely stored in luxury real estate, generating profits if invested in Western

business interests, acquiring influence if used for political or philanthropic

donations—all the while multiplying the kleptocrat’s wealth into new sources of

power.

Unlike the legal community, however, most financial institutions are governed by the

Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) of 1970, which requires them to proactively report suspicious

financial activity to the U.S. Treasury. ... Not all financial services providers are

covered by this AML [Anti-Money-Laundering] framework, however: hedge funds, asset

managers, and the directors of family offices, for example, are not subject to any

affirmative reporting requirements. ...

Kleptocrats, or their agents, will solicit financial services providers operating

outside the U.S. AML regime not only to open bank accounts, provide financial advice,

or transfer funds, but also to present them with investment platforms or

opportunities or undertake deals on their behalf.

[Full report continues with more details and recommendations on financial services,

as well as on real estate services, lobbying and public relations services, and

fintech and cryptocurrency services.]

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication providing reposted

commentary and analysis on African issues, with a particular focus on U.S. and

international policies. AfricaFocus Bulletin is edited by William Minter.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please write to this

address to suggest material for inclusion. For more information about reposted

material, please contact directly the original source mentioned. For a full archive

and other resources, see http://www.africafocus.org

|