|

Algeria

Angola

Benin

Botswana

Burkina Faso

Burundi

Cameroon

Cape Verde

Central Afr. Rep.

Chad

Comoros

Congo (Brazzaville)

Congo (Kinshasa)

Côte d'Ivoire

Djibouti

Egypt

Equatorial Guinea

Eritrea

Ethiopia

Gabon

Gambia

Ghana

Guinea

Guinea-Bissau

Kenya

Lesotho

Liberia

Libya

Madagascar

Malawi

Mali

Mauritania

Mauritius

Morocco

Mozambique

Namibia

Niger

Nigeria

Rwanda

São Tomé

Senegal

Seychelles

Sierra Leone

Somalia

South Africa

South Sudan

Sudan

Swaziland

Tanzania

Togo

Tunisia

Uganda

Western Sahara

Zambia

Zimbabwe

|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

Africa/Global: World Trends in Inequality

AfricaFocus Bulletin

January 15, 2018 (180115)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

|

Editor's Note

"The divergence in inequality levels has been particularly extreme between Western

Europe and the United States, which had similar levels of inequality in 1980 but

today are in radically different situations. While the top 1% income share was close

to 10% in both regions in 1980, it rose only slightly to 12% in 2016 in Western

Europe while it shot up to 20% in the United States. Meanwhile, in the United States,

the bottom 50% income share decreased from more than 20% in 1980 to 13% in 2016." -

World Inequality Report, 2018

The first World Inequality Report, just released, represents sustained work by over

100 researchers to collect the best data available from multiple sources on income

and wealth inequality both within and between countries. The project is ongoing, and

the availability of data for different countries is very uneven. But for the first

time there is a common basis for comparison, and both data and analysis are available

to the public.

Notably, the project is also stressing the implications of the research for policy,

and exploring ways of presenting the data in user-friendly graphic formats. The

measures most often used are the percentage of national income (or wealth) held by

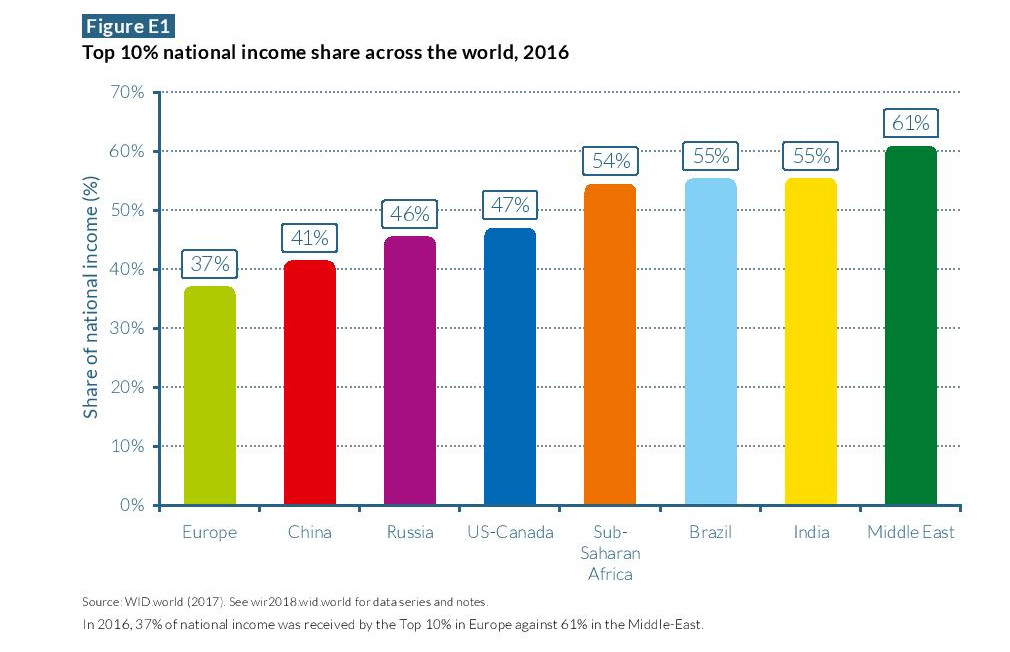

different percentile groups of the population. A striking regional comparison (see

graph below) highlights the percentage of national income received by the top 10% in 2016, from 37% in Europe to 61% in the Middle East. The percentage

held by the top 10% is 47% in North America, and around 55% in Brazil, India, and

sub-Saharan Africa. Not shown in this graph, but noted in a separate chapter and

available in the on-line database (http://wid.world/country/south-africa/),

the top 10% in South Africa received 65% of national income in 2012.

The report stresses that the levels of inequality are highly dependent on the

progressivity of tax policy, with the obvious implication that the Trump/Republican

tax bill will undoubtedly make inequality in the United States even more extreme.

The full database is available to access on-line or to download

at http://wid.world/data.

This AfricaFocus Bulletin contains excerpts from the executive summary of the report.

Another AfricaFocus Bulletin sent out today, and available at

http://www.africafocus.org/docs18/sa-us1801.php) contains excerpts from the

chapters on South Africa and the United States.

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on inequality, tax evasion, and related issues,

visit http://www.africafocus.org/intro-iff.php

Recent articles on closely related topics include:

Amanda Erickson, "The world’s 500 wealthiest people got $1 trillion richer in 2017,"

Washington Post, December 27, 2017

http://tinyurl.com/y7splebt, and

Gabriel Zucman, "Nearly 10% of the world’s wealth is held offshore by a few

individuals. The rest of us pay the price for this theft." Guardian, 8 Nov. 2017

http://tinyurl.com/y8apyp3v

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

World Inequality Report

Executive Summary

Full report and abundant additional information available at

http://wir2018.wid.world/

II. #What are our new findings on global income inequality?

We show that income inequality has increased in nearly all world regions in recent

decades, but at different speeds. The fact that inequality levels are so different

among countries, even when countries share similar levels of development, highlights

the important roles that national policies and institutions play in shaping

inequality.

Income inequality varies greatly across world regions. It is lowest in Europe and

highest in the Middle East.

Inequality within world regions varies greatly. In 2016, the share of total

national income accounted for by just that nation's top 10% earners (top 10% income

share) was 37% in Europe, 41% in China, 46% in Russia, 47% in US-Canada, and around

55% in sub-Saharan Africa, Brazil, and India. In the Middle East, the world's most

unequal region according to our estimates, the top 10% capture 61% of national income

(Figure E1).

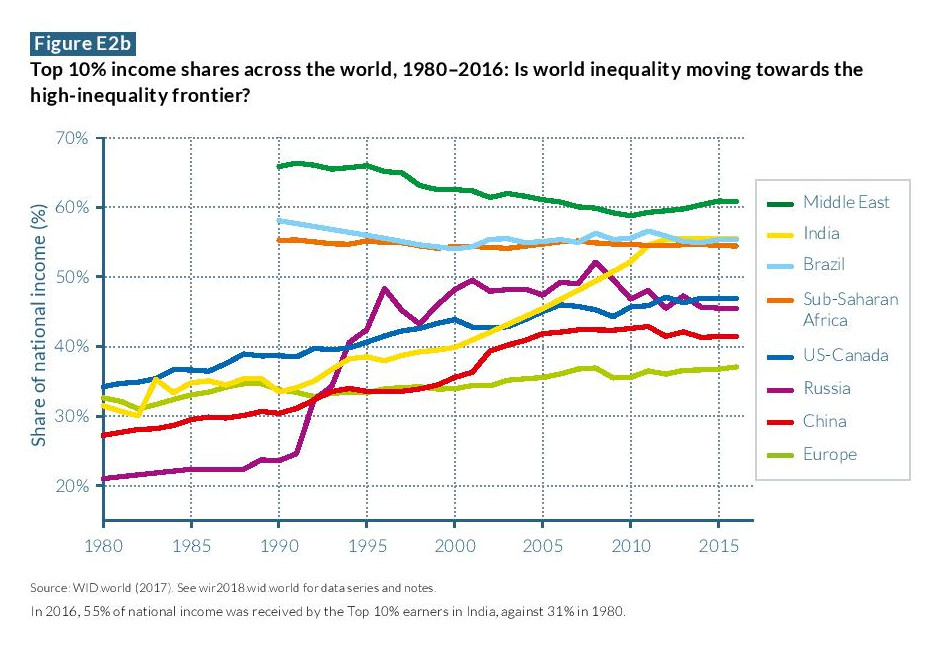

In recent decades, income inequality has increased in nearly all countries, but

at different speeds, suggesting that institutions and policies matter in shaping

inequality.

Since 1980, income inequality has increased rapidly in North America, China, India,

and Russia. Inequality has grown moderately in Europe (Figure E2a). From a broad

historical perspective, this increase in inequality marks the end of a postwar

egalitarian regime which took different forms in these regions.

- There are exceptions to the general pattern. In the Middle East, sub-Saharan

Africa, and Brazil, income inequality has remained relatively stable, at extremely

high levels (Figure E2b). Having never gone through the postwar egalitarian regime,

these regions set the world "inequality frontier."

- The diversity of trends observed across countries since 1980 shows that income

inequality dynamics are shaped by a variety of national, institutional and political

contexts.

- This is illustrated by the different trajectories followed by the former communist

or highly regulated countries, China, India, and Russia. The rise in inequality was

particularly abrupt in Russia, moderate in China, and relatively gradual in India,

reflecting different types of deregulation and opening-up policies pursued over the

past decades in these countries.

- The divergence in inequality levels has been particularly extreme between Western

Europe and the United States, which had similar levels of inequality in 1980 but

today are in radically different situations. While the top 1% income share was close

to 10% in both regions in 1980, it rose only slightly to 12% in 2016 in Western

Europe while it shot up to 20% in the United States. Meanwhile, in the United States,

the bottom 50% income share decreased from more than 20% in 1980 to 13% in 2016

(Figure E3).

- The income-inequality trajectory observed in the United States is largely due to

massive educational inequalities, combined with a tax system that grew less

progressive despite a surge in top labor compensation since the 1980s, and in top

capital incomes in the 2000s. Continental Europe meanwhile saw a lesser decline in

its tax progressivity, while wage inequality was also moderated by educational and

wage-setting policies that were relatively more favorable to low- and middle-income

groups. In both regions, income inequality between men and women has declined but

remains particularly strong at the top of the distribution.

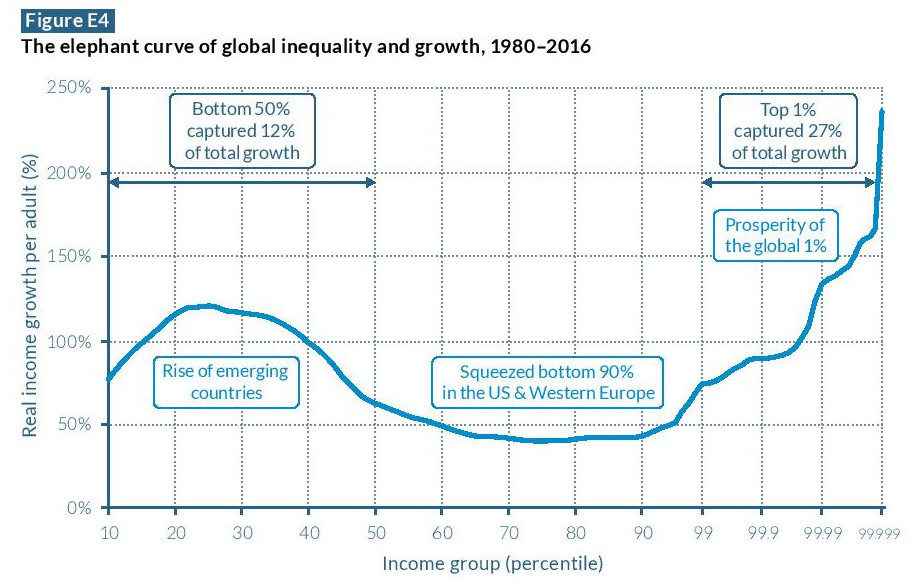

How has inequality evolved in recent decades among global citizens? We provide the

first estimates of how the growth in global income since 1980 has been distributed

across the totality of the world population. The global top 1% earners has captured

twice as much of that growth as the 50% poorest individuals. The bottom 50% has

nevertheless enjoyed important growth rates. The global middle class (which contains

all of the poorest 90% income groups in the EU and the United States) has been

squeezed.

At the global level, inequality has risen sharply since 1980, despite strong

growth in China.

- The poorest half of the global population has seen its income grow significantly

thanks to high growth in Asia (particularly in China and India). However, because of

high and rising inequality within countries, the top 1% richest individuals in the

world captured twice as much growth as the bottom 50% individuals since 1980 (Figure

E4). Income growth has been sluggish or even zero for individuals with incomes

between the global bottom 50% and top 1% groups. This includes all North American and

European lower- and middle-income groups.

- The rise of global inequality has not been steady. While the global top 1% income

share increased from 16% in 1980 to 22% in 2000, it declined slightly thereafter to

20%. The income share of the global bottom 50% has oscillated around 9% since 1980

(Figure E5). The trend break after 2000 is due to a reduction in between-country

average income inequality, as within-country inequality has continued to increase.

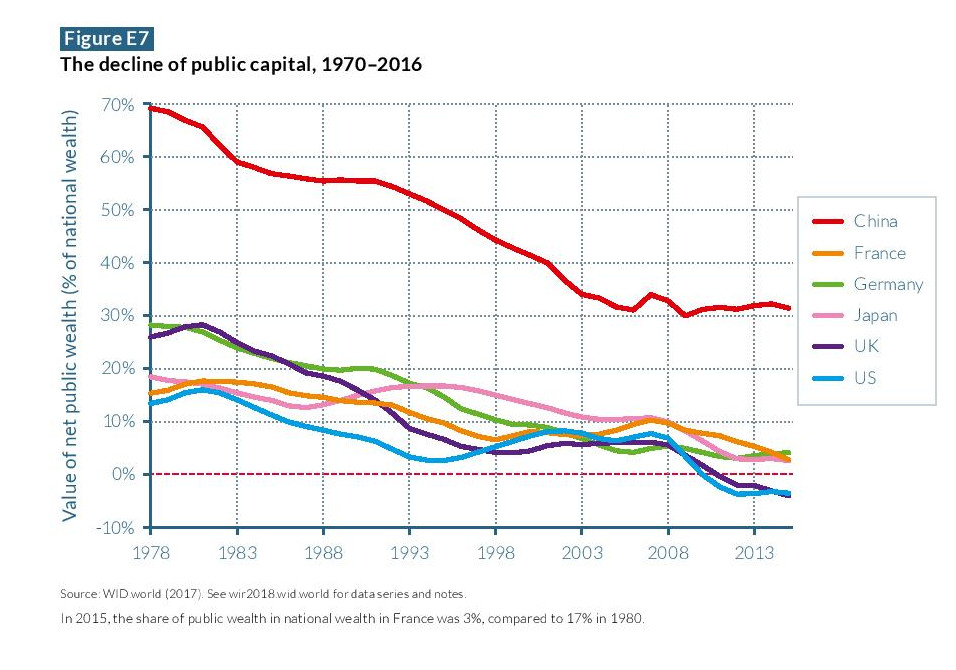

III. Why does the evolution of private and public capital ownership matter for

inequality?

Economic inequality is largely driven by the unequal ownership of capital, which can

be either privately or public owned. We show that since 1980, very large transfers of

public to private wealth occurred in nearly all countries, whether rich or emerging.

While national wealth has substantially increased, public wealth is now negative or

close to zero in rich countries. Arguably this limits the ability of governments to

tackle inequality; certainly, it has important implications for wealth inequality

among individuals.

Over the past decades, countries have become richer but governments have become

poor.

- The ratio of net private wealth to net national income gives insight into the total

value of wealth commanded by individuals in a country, as compared to the public

wealth held by governments. The sum of private and public wealth is equal to national

wealth. The balance between private and public wealth is a crucial determinant of the

level of inequality.

- There has been a general rise in net private wealth in recent decades, from

200–350% of national income in most rich countries in 1970 to 400–700% today. This

was largely unaffected by the 2008 financial crisis, or by the asset price bubbles

seen in some countries such as Japan and Spain. In China and Russia there have been

unusually large increases in private wealth; following their transitions from

communist- to capitalist-oriented economies, they saw it quadruple and triple,

respectively. Private wealth–income ratios in these countries are approaching levels

observed in France, the UK, and the United States.

- Conversely, net public wealth (that is, public assets minus public debts) has

declined in nearly all countries since the 1980s. In China and Russia, public wealth

declined from 60–70% of national wealth to 20–30%. Net public wealth has even become

negative in recent years in the United States and the UK, and is only slightly

positive in Japan, Germany, and France. This arguably limits government ability to

regulate the economy, redistribute income, and mitigate rising inequality. The only

exceptions to the general decline in public property are oil-rich countries with

large sovereign wealth funds, such as Norway.

V. What is the future of global inequality and how should it be tackled?

We project income and wealth inequality up to 2050 under different scenarios. In a

future in which "business as usual" continues, global inequality will further

increase.

Alternatively, if in the coming decades all countries follow the moderate inequality

trajectory of Europe over the past decades, global income inequality can be reduced--

in which case there can also be substantial progress in eradicating global poverty.

The global wealth middle class will be squeezed under "business as usual."

- Rising wealth inequality within countries has helped to spur increases in global

wealth inequality. If we assume the world trend to be captured by the combined

experience of China, Europe and the United States, the wealth share of the world's

top 1% wealthiest people increased from 28% to 33%, while the share commanded by the

bottom 75% oscillated around 10% between 1980 and 2016.

- The continuation of past wealth-inequality trends will see the wealth share of the

top 0.1% global wealth owners (in a world represented by China, the EU, and the

United States) catch up with the share of the global wealth middle class by 2050.

Tax progressivity is a proven tool to combat rising income and wealth inequality

at the top.

Research has demonstrated that tax progressivity is an effective tool to combat

inequality. Progressive tax rates do not only reduce post-tax inequality, they also

diminish pre-tax inequality by giving top earners less incentive to capture higher

shares of growth via aggressive bargaining for pay rises and wealth accumulation. Tax

progressivity was sharply reduced in rich and some emerging countries from the 1970s

to the mid-2000s. Since the global financial crisis of 2008, the downward trend has

leveled off and even reversed in certain countries, but future evolutions remain

uncertain and will depend on democratic deliberations. It is also worth noting that

inheritance taxes are nonexistent or near zero in high-inequality emerging countries,

leaving space for important tax reforms in these countries.

A global financial register recording the ownership of financial assets would

deal severe blows to tax evasion, money laundering, and rising inequality.

Although the tax system is a crucial tool for tackling inequality, it also faces

potential obstacles. Tax evasion ranks high among these, as recently illustrated by

the Paradise Papers revelations. The wealth held in tax havens has increased

considerably since the 1970s and currently represents more than 10% of global GDP.

The rise of tax havens makes it difficult to properly measure and tax wealth and

capital income in a globalized world. While land and real-estate registries have

existed for centuries, they miss a large fraction of the wealth held by households

today, as wealth increasingly takes the form of financial securities. Several

technical options exist for creating a global financial register, which could be used

by national tax authorities to effectively combat fraud.

More equal access to education and well-paying jobs is key to addressing the

stagnating or sluggish income growth rates of the poorest half of the

population.

- Recent research shows that there can be an enormous gap between the public

discourse about equal opportunity and the reality of unequal access to education. In

the United States, for instance, out of a hundred children whose parents are among

the bottom 10% of income earners, only twenty to thirty go to college. However, that

figure reaches ninety when parents are within the top 10% earners. On the positive

side, research shows that elite colleges who improve openness to students from poor

backgrounds need not compromise their outcomes to do so. In both rich and emerging

countries, it might be necessary to set trans- parent and verifiable objectives--

while also changing financing and admission systems-- to enable equal access to

education.

- Democratic access to education can achieve much, but without mechanisms to ensure

that people at the bottom of the distribution have access to well-paying jobs,

education will not prove sufficient to tackle inequality. Better representation of

workers in corporate governance bodies, and healthy minimum-wage rates, are important

tools to achieve this.

Governments need to invest in the future to address current income and wealth

inequality levels, and to prevent further increases in them.

Public investments are needed in education, health, and environmental protection

both to tackle existing inequality and to prevent further increases. This is

particularly difficult, however, given that governments in rich countries have become

poor and largely indebted. Reducing public debt is by no means an easy task, but

several options to accomplish it exist--including wealth taxation, debt relief, and

inflation--and have been used throughout history when governments were highly

indebted, to empower younger generations.

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication providing reposted

commentary and analysis on African issues, with a particular focus on U.S. and

international policies. AfricaFocus Bulletin is edited by William Minter.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please write to this

address to suggest material for inclusion. For more information about reposted

material, please contact directly the original source mentioned. For a full archive

and other resources, see http://www.africafocus.org

|