|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

Africa: Migration Reports Show Complex Realities

AfricaFocus Bulletin

August 27, 2018 (180827)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

"In the case of Africa, the very idea that the situation to be faced is a rapidly

increasing “migration crisis” driven by a growing number of young men and women

desperately trying to enter Europe denies the basic facts [such as that]

the vast majority of Africans move within the continent; most Africans move for

reasons of work, study and family; and most Africans living abroad are not from the

poorest sections of their societies of origin." - UN Economic Commission for Africa,

Situation Analysis

The images of African migrants drowning in the Mediterranean or trying to cross the

barbed-wire fences between Morocco and the Spanish enclave of Ceuta, while anti-immigrant

politicians in the European Union rant against migrant "invaders," are

real. But their prominence in the news is misleading, as made clear by reports by

international agencies and scholars as well as news coverage by journalists willing

to take the time to explore in greater depth.

In fact, notes the report cited above and excerpted in this AfricaFocus Bulletin,

"African migration is not necessarily essentially different from migration in and

from other world regions. In fact, Africans are underrepresented in the world migrant

population and Africa has the lowest intercontinental outmigration rates of all world

regions."

Moreover, as stressed in the latest report from the UN Conference on Trade and

Development, cited below, migration and development as normal phenomena should be

mutually reinforcing. Instead of trying to curb migration, both source and

destination countries should be trying to maximize the benefits for both sides, while

at the same time protecting both voluntary and forced migrants from human rights

abuses.

Increasing restrictions with walls and stepped-up policing of borders, argues a

recent analytical book, are themselves fueling violence, in contrast to an approach

that would regulate but not close off borders. [See Violent Borders, by Reece Jones,

Verso Books, 2016. https://amzn.to/2PDu3fP]

This AfricaFocus Bulletin contains excerpts from the two reports cited above, as well

as suggestions for sources to follow for regular in-depth coverage of migration

issues. Journalists face a difficult task in calling attention to crises while not

reinforcing stereotypes. But readers also have the obligation to put the stories in

context of deeper analysis.

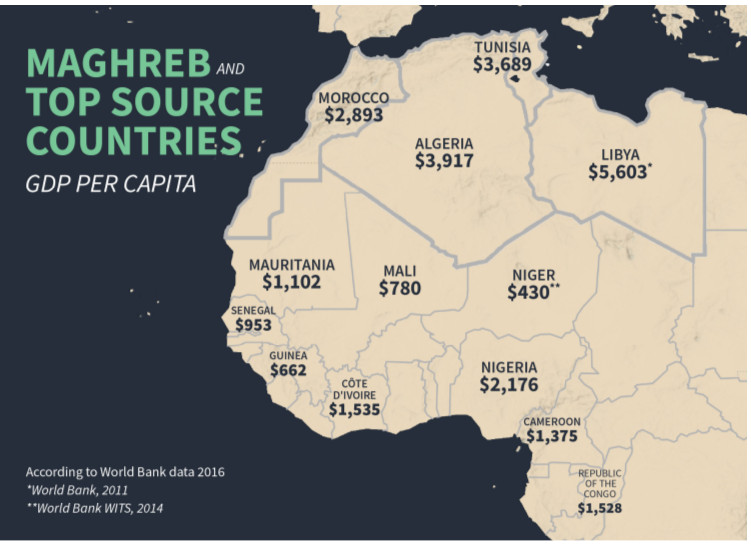

One example, of internal migration within Africa, illustrated below with a graphic

and links to relevant sources, is the migration from West Africa to North West Africa

(the Maghreb), not only as a route to Europe but also for education and employment

within the Magheb. That migration, as with migration out of Africa, features both

"normal" migration and the violence which comes from the attempts to curb migration

by destination-country states.

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on migration, visit

http://www.africafocus.org/migrexp.php

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

Sources for In-Depth News Reporting on Migration

For articles that give background as well as first-hand reporting on migration, two

regular sources to follow are IRIN News (http://www.irinnews.org/migration) and

Refugees Deeply (http://www.newsdeeply.com/refugees). You can bookmark these sites

and subscribe to regular email updates from either site.

A selection of recent articles from the two sites shows the range of topics:

Refugees Deeply, Aug. 16, 2018

Fear Dampens Hope Among Eritrean Refugees in Ethiopia

http://tinyurl.com/y987ymxs

Refugees Deeply, Aug. 16, 2018

School Started by Refugees Becomes One of Uganda’s Best

http://tinyurl.com/y83pd5lx

IRIN News, Aug. 16, 2018

Returning from Libyan detention, young Gambians try to change the migration exodus

mindset

http://tinyurl.com/y85ktsvz

IRIN News, Aug. 7, 2018

Meet “Baba IDP”: the local hero making sure Boko Haram victims get healthcare

http://tinyurl.com/y8npyu2z

Refugees Deeply, Aug. 2, 2108

Unlike Salvini, Italians Still Believe in Welcoming Strangers

http://tinyurl.com/ya74nuo9

IRIN News, July 19, 2018

From the hopeful refugee to the frustrated detainee, meet the real people stuck in

Libya

http://tinyurl.com/y9r839h2

Refugees Deeply, July 10, 2018

Why Algeria Is Emptying Itself of African Migrant Workers

http://tinyurl.com/y7l3hn8s

IRIN News, July 5, 2018

Thousands of Sudanese fled Libya for Niger, seeking safety. Not all were welcome

http://tinyurl.com/y96wewa4

African Regional Consultative Meeting on the Global Compact on Safe, Orderly and

Regular Migration

Addis Ababa, 26 and 27 October 2017

Draft report 1

Situation analysis

Patterns, levels and trends of African migration

United Nations Economic Commission for Africa

http://www.uneca.org – Direct URL: http://tinyurl.com/y9vgjake

[Excerpts only – see full 33-page report for footnotes, graphs, and references.]

This document has been drafted by Hein de Haas, and incorporates insights from the

subregional reports prepared by Papa Demba Fall, Pierre Kamdem, Caroline Wanjiku

Kihato, David Gakere Ndegwa and Ayman Zohry.

Introduction

1. More than migration in other world regions, African migration is commonly

portrayed as a phenomenon driven by poverty, violence and other forms of human

misery. Media images and political narratives routinely portray African migrants as

victims, who easily fall prey to “unscrupulous” smugglers and human traffickers who

“ruthlessly” exploit their desperation to reach the European “Eldorado”. Images of

rickety boats packed with African migrants and refugees arriving on European shores

and the increasing death toll this involves add to the image of an increasing

“migration crisis”. In the media, in policy and in some academic circles, a dominant

narrative is that fast population growth and persistent poverty and conflict in

Africa combined with environmental degradation and climate change threaten to lead to

a possibly uncontrollable increase in the number of young Africans desiring to cross

towards Europe and other overseas destinations (see Collier 2013). Such ideas of an

African exodus tap into deep- rooted fears of an impending “migration invasion” that

may well spiral out of control and that therefore needs to be dealt with as a matter

of urgency.

2. The most common “solutions” for the perceived migration crisis proposed by

Governments and international organizations typically consist of a blend of:

(a) Preventing unauthorized migration by [sic] “fighting” and “combating” smuggling

and trafficking (through intensified border patrolling and policing in transit

countries);

(b) Deportation or pressuring unauthorized migrants and rejected asylum seekers into

“voluntary return” or “soft deportation” (Boersema, Leerkes and van Os 2014; Pian

2010) (through readmission agreements with origin and transit countries such as

Libya, Morocco, Senegal and Turkey);

(c) Addressing the root causes of migration by reducing poverty and increasing

employment in African countries (particularly through aid (Böhning and SchloeterParedes

1994), which has increasingly become conditional on collaboration with

readmission of unauthorized migrants);

(d) Informing and sensitizing prospective migrants about the dangers of

(unauthorized) migration and the arduous circumstances in Europe (through media

campaigns, artistic events, and other activities (see Pelican 2012));

3. Such narratives tend, however, to be based on a number of questionable assumptions

about the nature and drivers of African migration, in particular, and migration from

and towards developing countries more generally. In the case of Africa, the very idea

that the situation to be faced is a rapidly increasing “migration crisis” driven by a

growing number of young men and women desperately trying to enter Europe denies the

basic facts that:

- The vast majority of Africans move within the continent.

- Africa is the least migratory region in the world.

- Most Africans move for reasons of work, study and family.

- Most Africans living abroad are not from the poorest sections of their societies of

origin.

- Unauthorized overland and maritime journeys represent a minority of all moves.

- Only a very small fraction of unauthorized migration can be characterized as

“trafficking” (see Kihato 2017).

4. Such basic facts also make it clear that African migration is not necessarily

different in its essence from migration in and from other world regions. The whole

idea that African migration is somehow “exceptional” seems – largely unconsciously –

to tap into European stereotypes and colonial ideologies about Africa as a continent

of general disorder, violence and poverty, which partly served to justify colonial

occupation, with Europeans intervening to impose order, peace and prosperity (see

Davidson 1992). Such stereotypes perpetuate the idea that African countries somehow

need to be “helped” to foster development and manage migration – which in practice

often amounts to “externalizing” European political agendas aimed at an increased

policing of African borders and the overall criminalization of migration and

smuggling (Brachet 2005; Kihato 2017). That, in turn, often clashes with the desire

of African Governments to liberalize internal movement and to proceed to the full

implementation of the various treaties signed on the protection of migrants and

refugees.

5. Furthermore, the idea that African prospective migrants need to be informed about

the dangers of the journey, that they need to be “rescued” from the hands of

smugglers and traffickers and that they would be better off if they had stayed at

home, is based on the paternalistic assumption that most African migrants do not know

what is in their own best interest. Many African (and other) migrants must deal with

exploitative recruiters and employers and although many migrants’ expectations of

life at their destination will remain unfulfilled, and notwithstanding the fact that

thousands of migrants have died while crossing borders in recent decades (see Crawley

and others 2016b; Perkowski 2016), the idea is, nevertheless, deeply problematic that

African migration is a largely desperate and generally irrational response to

poverty, violence and human misery at home. First, it reduces (poor, African)

migrants to victims and denies their capability (their “agency”) to make reasoned and

rational decisions for themselves. Second, it taps into stereotypes about Africa as a

region of poverty, violence and general disorder in which a deepening humanitarian

crisis is causing an increasing exodus of desperate young people from the continent.

Such stereotypes about African “misery migration” continue to be fuelled by media

images about the phenomenon of trans-Mediterranean “boat migration’ and political

narratives about an impending migration invasion.

6. Third, it misinterprets the nature and causes of African migration as essentially

different and exceptional compared to migration elsewhere. This does not of course

mean that poverty and violence are irrelevant for understanding African migration,

but that there is a risk of “pathologizing” African migration as a largely desperate

“flight from misery” and a response to destitution and population pressures.

7. Fourth, and most crucially, such representations of migration as the antithesis of

development are based on flawed assumptions of the fundamental causes of this

migration. In particular, they ignore increasingly robust scientific evidence that,

particularly in low-income countries, processes of economic and human development

tend to increase internal and international “outmigration” (Clemens 2014; de Haas

2010b; Skeldon 1997; Zelinsky 1971),

8. Such evidence upsets popular but misleading push-pull models, which predict that

most migration should occur from the poorest communities and societies. This

illustrates the need for a fundamental rethinking of the nature and causes of human

migration. That is particularly relevant in the context of African migration, which

is still predominantly cast in essentialist portrayals driven by sensationalist media

images and political crisis narratives. To contribute to such an effort, this

situation analysis aims to achieve an evidence-based understanding of the nature and

drivers of African migration over the post-Second World War period.

9. The present report will start by reviewing the main patterns and trends of African

migration over the past decades. While focusing on international migration, the

analysis will not artificially ignore internal migration, based on the understanding

that movement within and across borders are intrinsically interlinked (King and

Skeldon 2010) and that they stem from the same processes of social transformation and

development (de Haas 2010b).

10. The analysis will draw mainly on, first: our own analysis of available migrant

population (“stock”) and migrant flow data, such as that obtained from the United

Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs and the Determinants of

International Migration project; second: it will draw on available empirical studies

from African countries and also on the subregional reports that have been prepared

for the Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) in concordance with this regional report

(Fall 2017; Kamdem 2017; Kihato 2017; Ndegwa 2017; Zohry 2017). Where appropriate,

however, this analysis will occasionally draw on evidence gathered in other

developing regions or global analyses in order to assess the extent to which African

experiences resemble – or differ from – more general evidence on the characteristics,

patterns and drivers of human migration as well as the role that policies play in

affecting these.

...

Conclusion

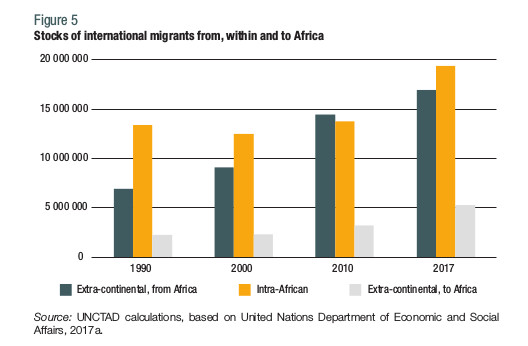

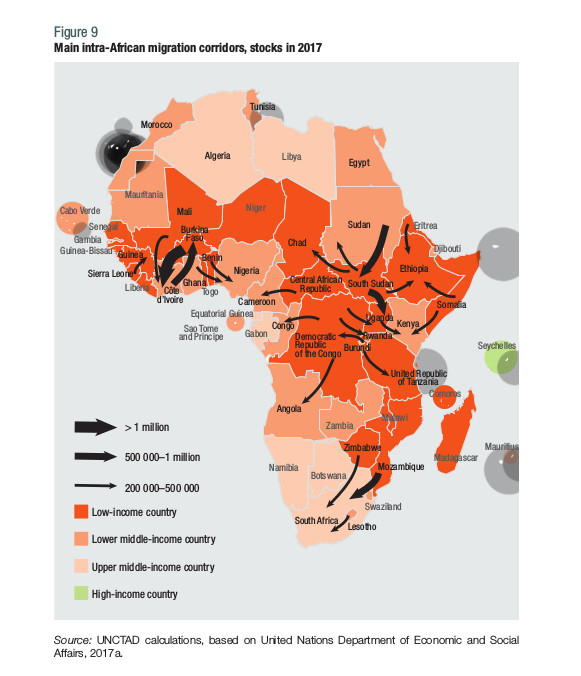

56. The preceding analysis highlights interesting figures and trends on African

migration. Although political narratives and media images focus on the purported

“exodus” of Africans to Europe, the bulk of African migrants move within the

continent. However, the overall intensity of intra-African international migration

has remained stable in recent years. This stagnation of migration intensities seems

to be related to the imposition of migration barriers which reduce unrestricted

migration. Given the dominance of intra-African migration, it is appropriate that the

migration discourse, policy responses and research interests should focus more on

this form of migration.

57. The idea that African migration is somehow “exceptional” seems to tap into

stereotypes. African migration is not necessarily essentially different from

migration in and from other world regions. In fact, Africans are underrepresented in

the world migrant population and Africa has the lowest intercontinental outmigration

rates of all world regions. Africa has also re-emerged as a migration destination,

particularly for Chinese workers and merchants as well as European skilled workers,

retirees and other “expats”. The absolute number of international migrants living on

African soil has grown from an estimated 20.3 million in 1990 to an estimated 32.5

million in 2015.

58. The share of African-born people living outside of the continent has shown a

slight increase – from 1.1 per cent in 1990 to 1.4 in 2015. This increase is high and

rising in absolute terms – although still relatively small in terms of the proportion

of Africans in the global migrant population. This increase has, however, been

largely due to legal, registered and thus “orderly” migration rather than to a

rising, disorderly and potentially uncontrollable tide of

59. Although more research is needed to corroborate this hypothesis, the increasing

policy focus on selection of skilled migrants by OECD countries has facilitated the

emigration of educated and relatively well-off Africans, but visa requirements and

border controls have decreased access of relatively poor Africans to legal migration

opportunities, particularly to Europe. On the one hand, this seems to have increased

their reliance on smuggling and unauthorized border crossings – the unauthorized

status of migrants increases the risks of labour exploitation, discrimination,

violence and other forms of abuse, which can sometimes evolve in situations of

trafficking.

60. On the other hand, the limited opportunities for legal migration to OECD

countries for lower-skilled workers seem to have partly stimulated the partial

geographical reorientation and diversification of African migration to countries in

the Gulf, China and elsewhere. Other explanatory factors behind this geographical

diversification of African emigration may include the waning influence of (post-)

colonial ties to Europe and the growing politico-economic and cultural influence of

China and the Gulf countries in Africa as well as the more liberal entry regimes in

the new destination countries.

Destination Maghreb

For a report on recent expulsions from Algeria, see

"Inside Algeria’s Mass Expulsions of Sub-Saharan Migrants

Aug. 7, 2018 - http://tinyurl.com/ydxao9or

For a report analyzing the nuances of "Changing Migration Patterns in North Africa,"

May 2, 2018, see https://www.csis.org/analysis/destination-maghreb

Economic Development in Africa Report 2018: Migration for Structural Transformation.

UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), May 2018

http://unctad.org / Direct URL: http://tinyurl.com/ybj28u8l

Foreword

Images of thousands of African youth drowning in the Mediterranean, propelled by

poverty or conflict at home and lured by the hope of jobs abroad, have fed a

misleading narrative that migration from Africa harms rather than helps the

continent. The latest edition of the UNCTAD flagship Economic Development in Africa

Report takes aim at this preconceived notion and assesses the evidence to identify

policy pathways that harness the benefits of African migration and mitigate its

negative effects.

This year, 2018, offers the international community a historic opportunity to realize

the first global compact for migration, an intergovernmentally negotiated agreement

in preparation under the auspices of the United Nations. Our contribution to this

historic process is the Economic Development in Africa Report 2018: Migration for

Structural Transformation.

Migration benefits both origin and destination countries across Africa. The report

argues that African migration can play a key role in the structural transformation

of the continent’s economies. Well-managed migration also provides an important

means for helping to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, both in Africa and

beyond.

The report adopts an innovative, human-centred narrative that explores how migrants

contribute to structural transformation and identifies opportunities for absorption

of extra labour in different sectors across the continent. African migrants include

from highly skilled to low-skilled persons, who migrate through legal channels and

otherwise.These migrants not only fill skills gaps in destination countries, but also

contribute to development in their origin countries. Children remaining in the origin

country of a migrant parent are also often more educated than their peers, thanks to

their parent’s migration. The connections that migrants create between their origin

and their destination countries have led to thriving diaspora communities. They have

also opened up new trade and investment opportunities that can help both destination

countries and origin countries to diversify their economies and move into productive

activities of greater added value.

Contrary to some perceptions, most migration in Africa today is taking place within

the continent. This report argues that this intra-African migration is an essential

ingredient for deeper regional and continental integration. At the same time, the

broad patterns of extra-continental migration out of Africa confirm the positive

contribution of migrants to the structural transformation of origin countries.

We believe this report offers new and innovative analytical perspectives, relevant

for both long-term policymaking and for the design of demand-driven technical

cooperation

projects, with a shorter time frame and will help Governments and other stakeholders

in reaching informed decisions on appropriate migration policies in the context of

Africa’s regional integration process.

It is our hope that these findings will improve policy approaches to migration for

African Governments, as well as for migration stakeholders outside the continent.

Mukhisa Kituyi

Secretary-General of UNCTAD

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication providing reposted

commentary and analysis on African issues, with a particular focus on U.S. and

international policies. AfricaFocus Bulletin is edited by William Minter.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please write to this

address to suggest material for inclusion. For more information about reposted

material, please contact directly the original source mentioned. For a full archive

and other resources, see http://www.africafocus.org

|