|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

West Africa/Global: Tax Evasion without Borders

AfricaFocus Bulletin

June 4, 2018 (180604)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

"On paper, the company that engineered and built the [$50 million mineral sands]

processing plant [in Senegal] was SNC Lavalin-Mauritius Ltd, a local division of SNC

Lavalin [Canada]. In reality, SNC Lavalin-Mauritius wasn’t involved. It was a shell,

created for the specific purpose of helping the engineering giant avoid tax payments.

The company had no construction equipment and no office of its own. It operated from

inside the Mauritius office of the offshoring law firm Appleby, which helped SNCLavalin

create the shell company." - West Africa Leaks

This case, in which a Canadian company evaded an estimated $8.9 million in taxes that

would have been due to the Senegalese government, through a shell company based in

Mauritius, is only one example from the West Africa Leaks series from the

International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) just released in late

May. ICIJ worked with 13 local journalists in 11 West African countries for the six-month

secret investigation, combining on-the-spot investigative journalism with ICIJ's

vast database of leaks previously reported in the Panama Papers and Paradise Papers

investigation.

These and other similar cases resulting in losses to tax revenues of both developing

and developed countries are often defined and defended by multinational companies and

their defenders as simply "tax avoidance" (that is, making clever use of existing

laws) rather than "tax evasion" (clearly illegal actions). But this ignores the often

significant ambiguity in what is "legal" as well as the role of special interests in

both writing and interpreting the laws and regulations.

In fact, there is a vast system of interlocked law firms, accounting firms, complicit

governments, corrupt individuals, and large companies that works systematically to

facilitate transactions that are at least morally and ethically questionable and

unfair, even when the legal case against them may be difficult to prove. For a

excellent recent update on why tax avoidance by multinational companies as well as

tax invasion should be considered "illicit financial flows," see the May 12, 2018

article by Sol Picciotto (http://tinyurl.com/ycvsqbda). A more extensive blog post by

the same author is available at http://tinyurl.com/y96xuldk

This AfricaFocus Bulletin contains excerpts from two articles in the ICIJ West Africa

Leaks series, one an overview of the 11-country investigation and the other a case

study of the construction project in Senegal cited above. The full series is

available on-line at https://www.icij.org/investigations/west-africa-leaks/

For a map of West Africa with a full list of stories on each country included, many

in French, go to http://tinyurl.com/y9nuhhel

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on tax evasion and related issues, visit

http://www.africafocus.org/intro-iff.php For previous Bulletins on West Africa, visit

http://www.africafocus.org/west.php

General Data Protection Regulation

AfricaFocus is in compliance with the new European Union General Data Protection

Regulation, and has updated its privacy notice on-line to provide a more detailed

explanation.

Data collected by AfricaFocus are used exclusively to manage and to improve its

information services to its readers.

See http://www.africafocus.org/privacy.php for more detail.

At the end of this Bulletin, as has always been the case for AfricaFocus, there is a

link you can use to unsubscribe from receiving these Bulletins. In addition to

unsubscribing, you also have the right to request any data kept by AfricaFocus and/or

to request permanent deletion of that data.

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

How Officials, Businesses And Traffickers Hide Billions From Cash-Starved Governments

Offshore

International Consortium of Investigative Journalists

May 22, 2018

https://www.icij.org/investigations/west-africa-leaks/

Reporting by Will Fitzgibbon

Contributors to this story: Moussa Aksar and Alloycious David

[Note: excerpts only. The full text of this overview article, with embedded links and

links to other specific country cases, is available at http://tinyurl.com/yb42huob

Government officials, arms merchants and corporations have spirited away millions of

dollars from destitute West African nations through offshore tax havens, an

investigation by journalists from the region and the International Consortium of

Investigative Journalists has found.

Offshore companies were set up for a global engineering firm that avoided paying

millions in taxes to Senegal, one of the world’s poorest countries; for a littleknown

entrepreneur who won a contract to build West Africa’s largest slaughterhouse

and for a well-connected arms trafficker from Chad. In several cases, the companies,

as well as the companies’ transactions and offshore bank accounts, were not declared

or are only now being revealed in more detail.

The findings were drawn from a collection of almost 30 million documents,

representing several leaked financial records obtained by and shared with ICIJ since

2012.

From Cape Verde’s islands of white-sand beaches and rocky volcanoes to Niger’s vast

deserts, West African countries are plundered by companies and individuals, while

governments do little to stem the flow.

West Africa accounts for more than one-third of an estimated $50 billion that leaves

the continent untraced or untaxed each year, according to the United Nations.

Overall, a combination of corruption, drug, human and weapons trafficking and other

furtive import and export activities strip Africa of three to 10 times as much as it

receives in foreign aid.

“For poor regions of the world like West Africa, the use of shell companies, tax

evasion, aggressive tax planning, tax havens and offshore bank accounts can be

dramatic” in the deprivation and suffering it creates, said Brigitte Alepin,

professor of taxation at the Université du Québec. “These countries are in need of

public finances, and these losses of tax revenues affect the basic services they can

offer to their citizens.”

The money reappears in safe deposit boxes in European banks, as equity in high-rise

New York condos and smooth limestone Parisian apartment buildings, far from the

collapsing hospitals and other buildings of West Africa. It also fills wealthy

investors’ pockets.

ICIJ partnered with 13 journalists on West Africa Leaks to investigate high-profile

individuals and powerful corporations in the region. The investigation included

journalists from six countries where reporters hadn’t before examined files

pertaining to the individuals and businesses.

The source material is millions of files that make up ICIJ’s four offshore databases:

Offshore Leaks, Swiss Leaks, Panama Papers and Paradise Papers.

Grande Côte mineral sands refinery on the coast of Senegal. Canadian construction

company evaded an estimated $8.9 million in taxes by using a shell company in Mauritius

for its conttract.

The leaked records include the secretive Persian Gulf real estate plans of a

candidate in this year’s Mali presidential election; the Swiss bank account of an

intimate friend of Togo’s hereditary dictatorship who manages the country’s overseas

real estate; and a Seychelles foundation directed by the childhood friend of

Liberia’s Nobel Peace Prize-winning former president, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf.

Often the offshore documents paint only a partial picture of the secretive financial

affairs of prominent and wealthy West African individuals and businesses. In several

cases, emails, spreadsheets and contracts don’t explain why a shell company was

created or how much money was held in a far-flung offshore bank account.

Yet the files provide rare insights about untouchable potentates who have long

benefited from weak tax enforcement and supine courts in countries that struggle to

hold them to account.

While several European nations have recovered small fortunes hidden offshore by

citizens and companies exposed by previous ICIJ leaks, no African country has

confirmed recovering a cent after previous revelations from these offshore troves.

Ousmane Sonko, a former Senegalese tax inspector who is now a member of parliament,

said many West African tax authorities are doubly plagued: They don’t have the means

to investigate complex foreign transactions, and, when investigators do make headway,

politicians find ways to torpedo their small successes.

Sonko said the situation is made worse by general ignorance of the importance of

corporate tax – or any tax – to society.

“When people don’t even understand what taxes are, acting on something like the

Paradise Papers is challenging,” Sonko said.

“If you talk about ‘tax havens’ in some countries in Africa, people will look at you

and think you’re insane.”

In the Central African country of Chad, David Abtour, who married the sister of an

ex-wife of President Idriss Déby, set up two companies after becoming involved in a

helicopter deal with Chad’s armed forces.

Abtour teamed up with the air force chief of staff to help Chad buy Russian

helicopters in 2006, French journalist Jacques-Marie Bougret reported. It was the

beginning of a lucrative association between Chad’s leaders and Abtour.

Chad, which has been identified as one of the world’s 10 least developed countries,

was at the time fighting Sudanese-backed rebel groups. In April 2006, rebels and

government forces clashed close to Chad’s National Assembly palace in fighting that

killed hundreds.

Chad’s army crushed the rebels, who had launched the attack from Sudan’s Darfur

region, with tanks and attack helicopters – weaponry that proved critical in the

scrappy, small-scale conflict.

At the time, Chad was declared the most “highly corrupt” country in Transparency

International’s global corruption rankings. Deby’s government starved schools, roads

and hospitals while lavishing millions of dollars on the military.

Politicians and rebels quarreled over a billion-dollar tax windfall from Chad’s oil

boom, exacerbating instability. “Chadians are watching to see who will try to take

the money, and how,” a New York Times guest columnist wrote in 2007.

From operating bases in Chad, Dubai and Paris, Abtour and his contacts provided Chad

with ammunition in 2007, according to Bougret. Abtour fell out of favor in 2008,

Bougret reported, after Chad’s prime minister replaced the head of defense.

The next year, Abtour set up two shell companies in Panama, according to the Panama

Papers. One company, Bickwall Holdings Inc., had a bank account in Switzerland with

HSBC Private Bank. The other, Tarita Management Corp., used UBS. In both cases, the

companies were set up to issue shares to Abtour in a way that kept his identity

concealed. Panamanian lawyers at Mossack Fonseca held no information on the

activities of the two companies, which were closed in 2013.

Abtour did not reply to requests for comment.

Countries involved in West Africa Leaks

Summary list (not complete) compiled by AfricaFocus Bulletin.

| In West Africa

| Outside West Africa

|

| Senegal |

Mauritius, Canada, UK, France, and Australia |

| Senegal |

Switzerland, France, USA, and Zimbabwe |

| Togo |

Switzerland |

| Niger |

British Virgin Islands, Australia, Saudi Arabia |

| Liberia |

Russia, Seychelles, Belgium |

| Mali |

Seychelles, Panama, Dubai |

| Ghana |

USA, UK, Cayman Islands, Cyprus, Luxembourg |

| Burkina Faso |

Luxembourg, Seychelles, Panama |

| Cape Verde |

Switzerland, Italy |

| Benin |

France, Panama, Monaco |

Côte d'Ivoire |

Bahamas and Panama |

| Côte d'Ivoire |

Panama, Bahamas, and UK |

| Nigeria |

USA (Chevron), Bermuda, Panama |

|

In Niger, emails and contracts from ICIJ’s Offshore Leaks investigation show, a

little-known New Zealand operator signed a $31.8 million contract with officials to

build West Africa’s most modern refrigerated slaughterhouse. Livestock is central to

Niger’s culture and accounts for 14 percent of all goods and services produced.

The slaughterhouse was started but not completed. Nine years, three court cases and

one coup d’etat later, it is unclear how much Niger paid for the nonexistent

slaughterhouse, why an obscure offshore company won the region’s most lucrative

livestock-related deal and whether any of the earnings were ever taxed.

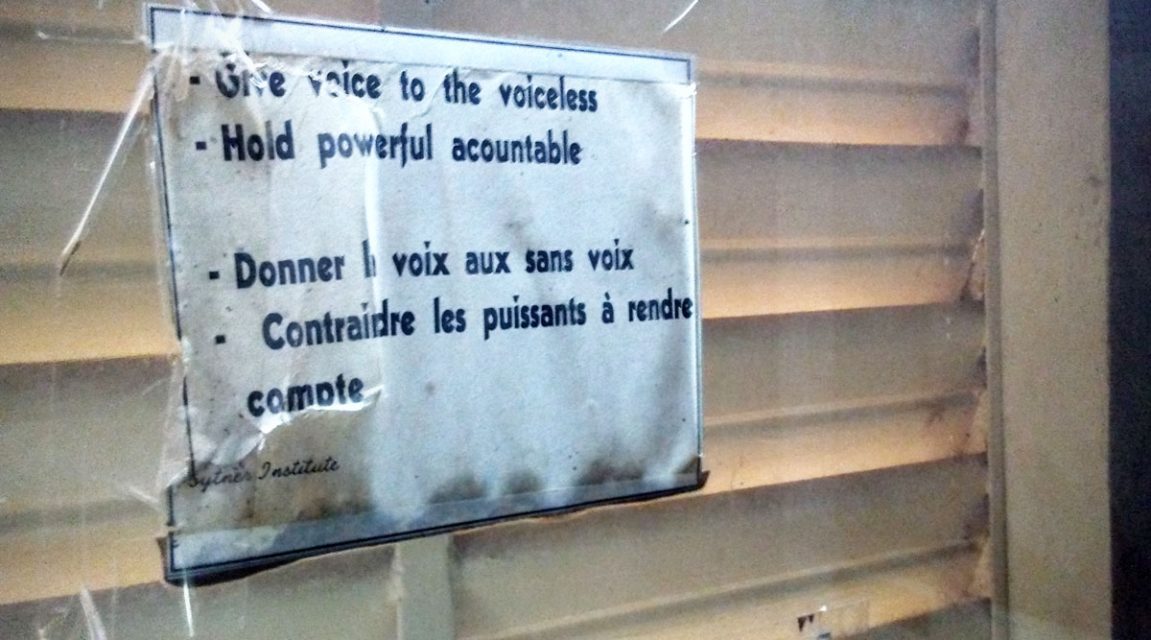

Sign inside the office of L'Evenement, where ICIJ member Moussa Aksar is editor in

chief.

According to Niger’s prime minister at the time, Seyni Oumarou, the company,

Agriculture Africa, and the operator, Bryan Rowe, were chosen for their “expertise

and know-how” and “global reputation.”

“Never heard of them,” said professor David Love, a slaughterhouse management and

construction expert who works with international organizations and national

governments, including in Africa.

Rowe set up seven companies in the British Virgin Islands, including Agriculture

Africa Ltd., according to the documents, leaked from the British Virgin Islands.

Agriculture Africa Ltd. was created in February 2009, and he signed the contract two

months later.

Rowe, whose background is primarily in emerging market telecommunications, told ICIJ

that only Agriculture Africa and Global Development Holdings International Ltd.

became operational.

Rowe said that progress on the slaughterhouse was on schedule until a military junta

overthrew the government in February 2010. Construction stopped. The new leaders

refused to pay Agriculture Africa’s bills for work completed since 2009, Rowe said.

He declined to say how much the company had been paid, citing confidentiality. Nor

did he explain why he chose to create the companies offshore.

Rowe said that he had won three court cases in Niger seeking payment for work

completed to date but that the judgments had not been enforced.

The Niger government did not respond to questions about the slaughterhouse.

Lack of responsiveness was one of myriad challenges faced by reporters during the

five-month West Africa Leaks project.

Recurrent, lengthy and erratic power and internet outages hobble reporting in many

countries in West Africa. Nigeria averages nearly 33 blackouts a month, many lasting

eight hours or more. Another problem is the limited access to even the most benign

documents or communications, and government agencies and politicians – even

presidential candidates – regularly refuse to comment.

Several ICIJ partners felt pressure to halt publication of their findings from

business leaders who threatened to withdraw newspaper advertising. Reporters also

struggled with unreliable, essential equipment to do their jobs. Two reporters worked

on computers whose malfunctions blacked out at least one-third of their screens.

ICIJ partnered with the Norbert Zongo Cell for Investigative Journalism in West

Africa (CENOZO), a West African nonprofit that supports regional collaborations and

receives funding from philanthropist billionaire George Soros’ Open Society

Initiative for West Africa.

Despite the difficulties, reporters connected many West African power players to

offshore accounts and companies. For instance, Liberia’s first female pharmacist,

Clavenda Bright-Parker, was the sole shareholder and director of a Seychelles

company, Greater Putu Foundation Ltd., according to Panama Papers documents.

Bright-Parker went to elementary school with former Liberian president Ellen Johnson

Sirleaf. As teenagers, at the cinema one evening, Bright-Parker introduced the future

president to her future husband and later took part in Johnson Sirleaf’s wedding as

maid of honor. Bright-Parker was also a personal envoy of the president and was

appointed chairwoman of Liberia’s medical regulatory agency.

The Panama Papers do not describe the specific purpose of Greater Putu Foundation

Ltd. or disclose whether the company had a bank account.

Bright-Parker’s offshore role in Greater Putu Foundation coincided with disagreements

between a Canada-based company in charge of the Putu iron ore mine and Liberia’s

government.

Canada’s Mano River Resources signed a deal to develop the mine in 2005 and later

sold its interest to the Russian global steel and mining company Severstal. Residents

and members of parliament have long complained that the owners of the mine did not

deliver on promises for development.

Mano River Resources’ co-founder, Guy Pas, did not describe Bright-Parker’s work in

detail but told ICIJ in an email that Bright-Parker “came recommended to take up this

role” with the Putu mine to “defend its interest at the highest level” against

ministerial pressure to have a larger mining company take over the project.

“Dealing with the Ministry was sometimes ‘complicated’,” Pas wrote, adding that

government officials never asked for money.

Reached by telephone, Bright-Parker said she had no knowledge of the Seychelles

company and asked reporters to call back for more details. She did not respond to

further calls or to emailed questions. Johnson Sirleaf said she was not aware of

Greater Putu Foundation Ltd. and never discussed the Putu mine with her friend.

Other West African findings from the offshore files examined by reporters highlight

techniques that profitable foreign companies use to reduce tax payments that could

otherwise be owed.

Canada’s SNC-Lavalin, one of the world’s largest construction firms, benefited from a

controversial treaty to avoid paying up to $8.9 million in taxes to Senegal.

...

[see separate article below]

One Company’s Tax ‘Heaven’ Is Senegal’s Tax ‘Hell’

A lopsided tax treaty between Mauritius and Senegal means, with the right paper work,

companies working in Senegal can avoid paying millions in taxes.

International Consortium of Investigative Journalists

May 22, 2018

https://www.icij.org/investigations/west-africa-leaks/

Reporting by Will Fitzgibbon

Contributors to this story: Momar Niang

[Note: excerpts only. Full text of this story, with additional embedded links,

available at http://tinyurl.com/y7dg7jbq

When one of the world’s largest engineering companies scored a $50 million deal to

build a processing plant in Senegal, one of the world’s poorest countries, it looked

to a tiny Indian Ocean island for help.

That island, Mauritius, has an established banking system, a level of political

stability unusual across Africa and a well-trained workforce.

It is also a renowned tax haven.

And Mauritius offered engineering company SNC-Lavalin a significant benefit: a

lopsided treaty signed with Senegal that, with the right paperwork, made it easy for

the Canadian firm to avoid up to $8.9 million in taxes.

That lost revenue is no small matter in Senegal, a country where nearly half of the

population lives in poverty, where 5 percent of newborns die and where one in six

children are stunted by years of poor nutrition. The forgone tax would have covered

half the cost of running Senegal’s largest public hospital for a year.

The Senegal-Mauritius treaty, concluded in 2004, is one among scores of agreements

that keep billions of dollars in tax revenue every year from reaching poor African

and Asian countries.

That was never the intention. Countries usually sign treaties to avoid taxing a

company’s income twice, once in each country. Developing countries, in particular,

have signed agreements in the hope that clarifying taxes paid by multinationals would

encourage investment and jobs in countries that multibillion dollar operations might

otherwise deem too risky.

Although originally hailed as deals that would benefit both sides of the agreements,

a chorus of critics increasingly denounces treaties between wealthier and developing

countries, particularly in Africa, as harmful to nations like Senegal.

Senegal is in West Africa, a poor region in one of the world’s most impoverished

continents. While parts of the capital, Dakar, teem with creperies and upscale

seaside fish restaurants, most of the countryside remains trapped in poverty. In

remote thatched-roof villages on Senegal’s lush coast, just 2 percent of the

residents receive piped water provided by public infrastructure.

In 2011, century-old Montreal company SNC-Lavalin signed a deal to design and build

the $50 million processing plant for the Grande Cote mineral sands mine. At the time,

the project appeared to represent great opportunity for Senegal.

The mine is now the largest operation of its kind in the world. It extracts mineralladen

sands from 60 miles of beach along Senegal’s coastline.

The sand yields, among other minerals, finely grained zircon, which is used in the

United States, Norway and beyond as a glaze that brightens ceramic kitchen tiles,

toilets and sinks. It also yields an ingredient in titanium dioxide, a whitener used

in toothpaste.

But the mine wasn’t universally welcomed. Local tensions began to flare in 2012

during construction of the processing plant. At least seven villages were forced to

make way for the project. Vegetable farmers and other residents complained of footdragging

resettlement schemes that displaced them from more-fertile to less-fertile

land.

In June 2017, members of Senegal’s parliament issued a report – obtained by

International Consortium of Investigative Journalists – that faulted Grande Cote on

several fronts. In particular, the report criticized the lack of diverse compensation

options for those who were resettled.

On paper, the company that engineered and built the processing plant was SNC LavalinMauritius

Ltd, a local division of SNC Lavalin.

In reality, SNC Lavalin-Mauritius wasn’t involved. It was a shell, created for the

specific purpose of helping the engineering giant avoid tax payments. The company had

no construction equipment and no office of its own. It operated from inside the

Mauritius office of the offshoring law firm Appleby, which helped SNC-Lavalin create

the shell company.

The company’s true nature as a conduit rather than as a contractor is revealed in

emails, invoices, financial statements and bank statements from the Paradise Papers,

a trove of 13.4 million documents, most from Appleby, which specializes in

administering tax-shelter companies.

SNC-Lavalin’s involvement with the mine ended when it finished building the

processing plant. A French-Australian consortium owns most of the operation, and the

government of Senegal holds a 10 percent stake.

By 2012, when almost all the work on the Senegalese plant was done, Grande Cote had

paid $44.7 million in fees to SNC-Lavalin Mauritius, according to the company’s 2012

financial statements and 24 invoices.

Senegal’s taxes disappear

Experts estimate that Senegal could have missed out on $8.9 million in taxes as a

result of the 2002 tax treaty between Senegal and Mauritius. Under the treaty,

companies like SNC-Lavalin with a subsidiary company in Mauritius can avoid Senegal’s

usual 20 percent tax on the kind of technical service fees paid to SNC-Lavalin. The

final tax rate in some cases can be reduced to zero. Senegal is one of only two

continental African countries with a Mauritius treaty with a zero percent tax rate.

SNC-Lavalin insists that it did not use the Mauritius company, SNC Lavalin Mauritius

Ltd., with the main goal of reducing its taxes. Its reasons for choosing the tax

haven, it said, instead included low political risk, a bilingual workforce, good

banks and “facility for doing business in Africa.”

It could have reduced its taxes in the same way by billing for services from Canada

under a treaty signed with Senegal, the company told ICIJ.

Experts consulted by ICIJ said it was unclear if the Canada treaty could have

delivered the same tax benefits to the company.

Senegal potentially could tax fees under the treaty with Canada, said Prof. Vern

Krishna from the University of Ottawa who is the managing editor of the legal

publication Canada’s Tax Treaties. He added that Senegal’s ability to tax would be

consistent with the United Nations’ philosophy of encouraging developing countries to

tax income “as soon as possible.”

A spokesman for Senegal’s tax office said it signed the treaty in the hope of a winwin

situation but now feels it is “unbalanced in Mauritius’ favor” and allows

companies to set up in Mauritius for treaty benefits only.

It is renegotiating Mauritius and waiting for the island’s response. “Failing that,”

the spokesman said, “Senegal may withdraw from the treaty – pure and simple.”

SNC-Lavalin said it was “entitled to rely on the Mauritius-Senegal Tax Treaty similar

to any other company based in Mauritius.”

But experts say that tax treaties of the kind that SNC-Lavalin used to avoid paying

millions to Senegal should be a thing of the past.

“You are legalizing the earning stripping-out of the country,” said Alexander

Ezenagu, a tax researcher at McGill University.

“It’s a redesign of neocolonialism,” Ezenagu said, who is Nigerian. “In the 1800s, in

the 1900s, they came with violence. Now, they come with sophisticated accounting

systems and the lure of investment. But no country needs investment if it’s not going

to be rewarded.”

Around the world, civil society, academics and members of parliament have criticized

many of the estimated 500-plus tax treaties signed between developed and developing

countries.

While the overall value of losses is not known, the International Monetary Fund

estimated that U.S. tax treaties cut the revenue of less developed countries by $1.6

billion in 2010. Dutch nonprofit SOMO estimated that developing countries lost more

than $1 billion in 2011 alone through tax treaties signed with the Netherlands. In

response to fears of inequitable deals, countries such as Rwanda, South Africa,

Zambia and Mongolia have cancelled or renegotiated some of their tax treaties.

Senegal and Mauritius present a sharp contrast. While a third of Senegal’s population

lives in poverty, Mauritius is considered Africa’s second-most-developed country and

one of its richest. When the two nations signed the agreement, officials said it

would spur development in both by encouraging investment in Senegal by Mauritius.

Increasingly, however, critics say the agreement has allowed foreign companies to

bypass Senegal’s tax laws with shell companies in Mauritius or elsewhere. The

companies created in Mauritius generally don’t invest in Senegal, but they do provide

huge tax savings to their parent companies, outside Africa, and deprive Senegal of

badly needed tax revenue.

Tax heaven or hell?

“A tax haven might be heaven for multinational companies to avoid taxes, but, for the

country, it’s hell,” said Ousmane Sonko, a former tax inspector who became a member

of Senegal’s parliament in 2017 after running on a platform on tax fairness.

Sonko is currently lobbying other members of parliament to reject a proposed treaty

with another tax haven, Luxembourg. “At the time when we should be talking about

ending the tax treaty with Mauritius,” Sonko said, “they are instead talking about

signing a new one with Luxembourg.” Luxembourg is also well known for its creation of

shell companies.

...

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication providing reposted

commentary and analysis on African issues, with a particular focus on U.S. and

international policies. AfricaFocus Bulletin is edited by William Minter.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please write to this

address to suggest material for inclusion. For more information about reposted

material, please contact directly the original source mentioned. For a full archive

and other resources, see http://www.africafocus.org

|