|

Algeria

Angola

Benin

Botswana

Burkina Faso

Burundi

Cameroon

Cape Verde

Central Afr. Rep.

Chad

Comoros

Congo (Brazzaville)

Congo (Kinshasa)

Côte d'Ivoire

Djibouti

Egypt

Equatorial Guinea

Eritrea

Ethiopia

Gabon

Gambia

Ghana

Guinea

Guinea-Bissau

Kenya

Lesotho

Liberia

Libya

Madagascar

Malawi

Mali

Mauritania

Mauritius

Morocco

Mozambique

Namibia

Niger

Nigeria

Rwanda

São Tomé

Senegal

Seychelles

Sierra Leone

Somalia

South Africa

South Sudan

Sudan

Swaziland

Tanzania

Togo

Tunisia

Uganda

Western Sahara

Zambia

Zimbabwe

|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

Horn of Africa: Interview with Kassahun Checole

AfricaFocus Bulletin

September 18, 2019 (2019-09-18)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

For over 36 years, Kassahun Checole has shepherded hundreds of

manuscripts into publication through his twin publishing houses

Africa World Press and Red Sea Press. He is widely respected among

scholars and activists in Africa and around the world as one of the

giants of African and African American publishing. Yet his own keen

insights on Africa´s past and present, particularly on Eritrea and

Ethiopia, are hardly to be found in print or on-line.

It is with great pleasure, therefore, that AfricaFocus presents

this transcript from a recent detailed interview with Kassahun

Checole by Walter Turner, on KPFA´s Africa Today program for July

22, 2019.

While the interview sketches in Checole´s personal history and

touches on the issues of the diaspora from the region, the emphasis

is on Ethiopia and Eritrea. It provides an exceptionally clear

exposition of the history of recent decades, leading up to the new

hopes for the region after the inauguration of Abiy Ahmed as prime

minister of Ethiopia in April 2018. As those who know him would

expect, the interview provides nuanced judgments based on wide-

ranging contacts in the Horn of Africa region and with the

diaspora.

For a catalog of books published and distributed by Africa World

Press and Red Sea Press, visit

http://africaworldpressbooks.com/.

In September 1994, Checole´s early career was featured in the New York Times,

under the title, “A Boy's Dream of Great Things Leads to a

Publishing House.”

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on Ethiopia and Eritrea, visit

http://www.africafocus.org/country/ethiopia.php and

http://www.africafocus.org/country/eritrea.php

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

Interview with Kassahun Checole by Walter Turner

July 22, 2019

Full audio available at

https://kpfa.org/episode/africa-today-july-22-2019/.

[Transcript by

Fantastic Transcripts. Slightly edited for clarity and length

by AfricaFocus.]

Walter Turner: You’re tuned into radio stations KPFA 94.1, KPFB

89.3, coming from the city Berkeley, KFCF 88.1 from the city of

Fresno, and K248BR coming from the city of Santa Cruz, online all

the time at http://www.kpfa.org.

In the background, sounds of music from Ethiopia, jazz between the

years 1969 and 1974, Ethiopiques.

Today, we’re going to speak with Kassahun Checole, publisher

extraordinaire of Red Sea Press, Africa World Press. He’s going to

be talking to us about developments in the Horn of Africa.

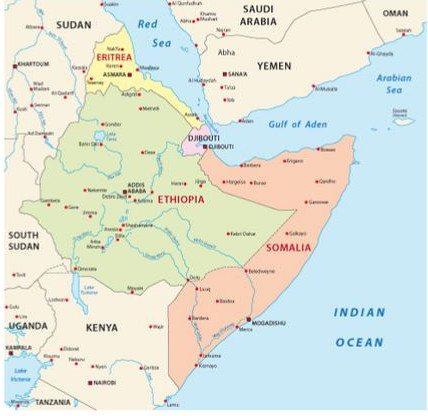

The country of Ethiopia is located in northeast Africa, has a

population of more than 100 million, bordered by the countries of

Eritrea, Djibouti, Somalia, Kenya, South Sudan, and Sudan. The

settled history of Ethiopia dates back beyond the ancient empire of

Aksum. Within the borders of Ethiopia, there are probably about

80-plus different linguistic groups. The contemporary history of

Ethiopia has been marked by invasions by Italy in the late 19th,

early 20th century, the leadership of Haile Selassie, the competing

interests of major powers for the strategic Horn of Africa, the

rule of the Derg throughout the 1980s, and the attempt at what many

characterize as ethno-federalism through the EPRDF, the Ethiopian

People's Revolutionary Democratic Front.

In 2018, after ongoing protests in the Oromo region, prime minister

Hailemariam Desalegn stepped down from office. This led to the

ascension of Dr. Abiy Ahmed as the prime minister. The political

agenda of Abiy Ahmed has led to forward steps to repair tattered

relations with Eritrea, releasing of political prisoners, and

reconfiguring longstanding roles in power based on ethnicity.

We are joined today on the phone by Kassahun Checole to discuss

Ethiopia, Eritrea, and the Horn of Africa. He is the president and

publisher of Africa World Press and the Red Sea Press. He hails

from the country of Eritrea in East Africa. He founded these

publishing houses in the mid-1980s. He began with a title by the

great Kenyan author, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, which was entitled The

Barrel of a Pen. He has taught at SUNY Binghamton. He has also

taught at El Colegio de Mexico in Mexico City. He has been

exclusively over the last decade or so working with Africa World

Press and Red Sea Press, putting out an impressive catalog of more

than a hundred titles per year, covering just about everything you

want to cover, some emphasis certainly on the African continent,

but certainly throughout the African diaspora, and working with

luminary presses such as Black Classic Press and Third World Press.

Kassahun, thanks for joining Africa Today.

Kassahun Checole: It’s my pleasure, Walter.

Turner: Good. Why did you enter into the field of publishing and

distribution?

Checole: Well, coming out of an academic background, I saw the

dearth of material on African and African American history. The

books that I used to use in my classes were going out of print as

fast as I can use them. So I decided that what we need is a

publishing house, and I didn’t see significantly a strong academic

publishing house. That’s where my interest was. Therefore, I

launched into publishing. That is after having come off five

years’ experience in Mexico and having seen the validity of their

own publishing and writing history – in other words, they were

writing and publishing their own history on their own. That makes

a difference. And I thought we needed – Africans and African

Americans need press publishing houses.

Turner: The publishing house we, to some degree, know about,

certainly. But there’s also a big part of your work which is

distribution. How crucial is the control or the narrative around

distribution toward your ultimate goals in terms of informing

African communities worldwide?

Checole: OK. Well, Walter, I came into distribution from a

necessity that was driven by the fact that when I started

publishing in 1983, I couldn’t find anyone who would carry my

books. The traditional distributors in the United States were

sympathetic, but they were not willing to carry black books in a

significant way or promote them in a significant way. I was being

told again and again that it’s good to publish black books, but

there’s no buyers. So I had to disprove that notion. And in 1985,

I began distributing not only my own books, but the books by other

black publishers in the United States and around the world.

Turner: How many books are you putting out per year at this point,

Kassahun, on average over your last – well, now it’s been more than

– you’re 25-plus years into this, right?

Checole: Not 25 – it’s been exactly 36 years now.

Turner: 36 years, OK.

Checole: Yes. And we are putting out – it fluctuates from

anything from 60 to a hundred books a year, depending upon how our

pocketbook looks like, which is not always in a positive sign. So

we’re doing quite a large number of books, but trying to slow down

and do more specialized books as well.

Turner: You’ve got some fantastic titles there. You’re doing the

thing from Black Classic Press, and when you look through your

pages, you see the titles by John Henrik Clarke and Asa Hilliard.

Is the interest increasing in what you’re doing and the type of

books that you’re putting out focusing on Africa?

Checole: Well, the numbers have actually decreased, but the

quality of readers has gone up. More and more readers are

interested in specific areas, particularly on the question of

politics, religion, history. This has been the strong point. We

are lucky we are working with sister companies, like Black Classic

Press and Third World Press, and other Black publishers who are

doing fantastic work in this area. So we bring them together along

with our own titles, and we see that we still, by and large, have

strong interest in reading. But the buying power has shifted a bit

because of the digital intervention. It’s a digital era, and

people have access to websites and they have access to the

internet, and some people do not want to go deeper, as they should.

The items that they find on Wikipedia and others like that think

they know enough. But as I said, the quality of readership is

increasing.

Turner: You’re originally from the country of Eritrea in the Horn

of Africa. People look at a map there – that piece that you see of

Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia there that borders the Red Sea. Is

there something about your experiences growing up, your family,

your experience during the political changes and evolution of

Eritrea that has motivated you in the directions that you work in,

Kassahun?

Checole: Well, I’m fortunate that I came from a family and from a

country that is literate, that has been in the industry of writing

and publishing for ages, before even the Western world entered the

writing and literary figures. So I was influenced as I grew up by

my access to church literature and other historical materials

written in my language and that of Ethiopia’s Amharic language.

Eventually, I also began to read materials in Italian and English

and a little bit of Arabic. So that background helped. When I

came to the United States in 1971, my interest in reading and

learning history increased significantly. I specialized in African

American history in undergraduate studies. That also really

increased the emphasis on my reading and love of literature.

Turner: In regards to the history of the region, do a couple of

things here for us, Kassahun. One, just give us a sketch so that

listeners know the depth of the historical background, the region

that we’re talking about. And secondly, the importance and how it

plays out – the fact that Ethiopia was a country that was never

colonized by Europeans. Talk about that region, Ethiopia, Eritrea,

as well as the roots of history, the roots of early human

development.

Checole: OK, let’s do three things. One is to say that the region

as a whole is the center of civilizations, from Meroë to Nubia to

Aksum to Egypt, and that is a significant part of the human

civilization that started and developed in the region. That is

one. And that historical fact most people don’t know.

The second is the area is the origin of both of the major Abrahamic

religions – the three major Abrahamic religions – Judaism,

Christianity, and Islam. Most people don’t even know this, but

that region played a significant role in advancing our modern

Abrahamic religions as we know them. We still practice those three

religions in the area. That is a significant one.

The third part is that this civilizational development in that area

has grown up with a historical parallel, which is the people of the

area were tenacious. They fought against all sorts of invaders.

In the Sudan, for example, we see the incredible struggle against

the Anglo-Egyptian empire, against the Turks, against, later on,

British imperialism, what have you. You can see the same thing

happening in Ethiopia and in Eritrea and Somalia.

So Ethiopia emerged as an independent nation throughout these years

except for five years of occupation. This was the fact that it was

protected from the interior by the existence of Eritrea as a sea

border society. So all outside interventions, actually, came

through Eritrea. The Turks, Egyptians, the Italians, the English

were able to penetrate east African region, as we know it, and into

Ethiopia through Eritrea. So Eritrea was both a victim of this

geographical existence, but also a very tenacious fighter against

all these invaders. Until 1935, Ethiopia was not penetrated. When

it does at Battle of Adwa in the late 19th century, it fought back

heroically and defeated the Italians in the Adwa battle. That is a

pan-African struggle that should be memorable for everyone to know.

Turner: How do we distinguish for listeners here as we go forward

and work our way towards contemporary developments – a couple of

other things to put out there. One, the legacy of Haile Selassie,

Emperor Haile Selassie. Secondly, for listeners, distinguish

between in some role of ethnicity or peculiarities the countries of

Ethiopia and Eritrea.

Source:

https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/where-is-the-horn-of-

africa.html. For a map also showing the independent but internationally not recognized Somaliland (to the east of Djibouti), click here.

Checole: OK. Well, both Ethiopia and Eritrea, you could say, are

a mosaic of peoples. We have in Ethiopia in particular hundreds of

ethnic compositions from all sorts of parts of Africa. It’s a very

difficult to now explain in a short manner the various migrations

inward and outward towards east Africa from as far away as southern

Africa, west Africa, and through the Sudanic belt movements to the

Bantu movements. There is huge amount of intervention of peoples

and cultures and languages to that area. So we call both Ethiopia

and Eritrea the mosaic of peoples. Any color, any language, any

culture that you can think of in Africa, you can find in this area.

So it is particularly important.

The second item is the external interventions, as I said, from the

Turks, the Anglo-Egyptian empire, the Italians, and recent times,

the American empire has played a significant role in the present

politics of both conflict and the struggle to resolve them.

Turner: And the leadership of Haile Selassie – the legacy of it

all the way up, I guess, to 1974.

Checole: Yeah. Well, Haile Selassie was, to start with, part of

what is called the Solomonic dynasty in Ethiopia. He ruled because

he led a group of monarchical elements in the society that wanted

to advance their interests. He was a feudal ruler, by and large.

He really lived and existed as such. And people were highly

oppressed, particularly the peasant society of Ethiopia.

But if you look at him for what he’s worth, he was a progressive

element for his time. He played a significant role in bringing

about modern education, modern technology, some form of legal

reformations in the society. But still, he remained a very

oppressive ruler. So there was a coup d’état – a revolution

against him led by movements from the north, mainly from Eritrea,

which wanted to get rid of the occupation of the Ethiopian

government, and Tigray, which was one of the most oppressed

societies in Ethiopia. Those groups of people led a very strong

revolution that lasted from 13 to 17 years in the Tigray case and

won the final success in 1991. So it is very, very critical to

think about Haile Selassie in both positive ways and also in his

character as a feudal ruler.

Turner: As we talk – we’re speaking with Kassahun Checole. He is

the CEO of Africa World Press and Red Sea Press. We’re talking

about the Horn of Africa, working our way to a discussion about the

most contemporary developments. There’s a couple phases that we’re

walking through, and one, of course, is the phase of the Derg. The

other is the phase, of course, of the most recent period, where

we’ve had the leadership of Meles Zenawi, during the phase, of

course, of the independence of Eritrea in 1991 and the declaration

of Eritrea as a state, and then the most contemporary development.

You can walk back on any of those, if you’d like to, Kassahun.

This notion of what we see in the EPRDF, how do you characterize

that? I see the word ethno-federalism. How do you characterize

that, why did it come together, and what were some of the

challenges inherent in that degree of union?

Checole: Yeah, if I can go back one more step –

Turner: Please do.

Checole: – and say that the coming of the Derg in 1974 is an

important milestone. The revolutionary action taken by the

military in 1971 came about for two main factors, but many other

factors as well. One is that the military could not win the battle

against the Eritrean freedom fighters. They were angry with the

government of Ethiopia. They were losing the war and losing so

many of their soldiers. As a result, they didn’t see a way out

except a political resolution. That’s one.

Second, the country was going through a tremendous amount of famine

and suffering, and the Haile Selassie government had neglected

dealing with those issues in a proper manner, to a point that

students in the university and other places who had been active for

social reformation in the society became the leading ideological

leaders of the military rulers.

So in 1974 to 1991, we had military rule in Ethiopia which still

did not resolve the troubles in the country, which are, in my

opinion, three. One, the war with Eritrea. Two, the suffering of

the people – the poverty, the hunger, what have you. And three,

the question of how to deal in a just manner with the various

ethnic and linguistic differences within the country. So

socioeconomic factors took over, and we come to 1991 with the

EPRDF, which was made up of four regional ethnic groups put

together by the Liberation Front – led by Tigray People’s

Liberation Front from the north, and has been ruling since then,

and still is in power, actually, at least in name, if not in fact.

Turner: Walk us through that, as a person from that region who has

followed that, this attempt to unite Amharic-speaking people,

Oromo-speaking people, Tigrayan-speaking people, the southern

provinces, and the other what – I guess it would be the other five

provinces of Ethiopia. What were the challenges?

Checole: Well, as I said, the troubles of the country are

internally socioeconomic factors. Societally, the country, as I

said, was divided into different regions, into different ethnic

groups. Bringing all of this diversity into a singular united

front is not easy. There were people who actually lived

comfortably, relatively speaking. Then there were others who were

oppressed because of their language, their ethnicity, and for other

historical factors.

For example, a good example is the Oromo people, by and large, one

of the largest ethnic groups in Ethiopia. But the Oromos have

always complained that their history was misinterpreted and that

their personality as a people have been distorted. They have been

insulted as a rival ethnic cultural group, and they have been

repressed and marginalized by the state of Haile Selassie, the

Derg, and others.

So the Oromos really have very serious complaint to make on the

state structure. And they showed that, as you saw, in the last

four years in particular, leading up to the breakup of the EPRDF

internally and the coming of Dr. Abiy Ahmed. So those are the

major factors.

The other, of course, we talked about – Eritrea, which gained its

independence in 1993. That nation and that people have been

fighting for their freedom for over 30 years, which at that time

was one of the largest armed struggles for liberation in Africa.

They created a society that was supposed to be a democratic,

socially progressive, and economically advanced society. But in

1993, definitely, they declared independence.

But the problems of Ethiopia are further than that. It’s the

economic structure – the land issue, which was partially resolved

by the Derg, who nationalized the land and made it available to the

landless and gives the peasants in Ethiopia a little bit of

relative freedom to do what they can do with the small piece of

land they had. So as an agriculture-based society that really have

had no positive input from the state until the coming of the EPRDF,

which if it has done anything positive, it is providing the peasant

society a leeway to a modern agricultural system, a leeway to a

modern marketing system, and getting rid of the middle classes that

used to exploit the peasantry was one of the biggest achievements.

Today, in my opinion, the Ethiopian peasantry is probably one of

the best-growing and the best-advanced parts of the society,

because they are able to till their land and market their grains

properly.

Turner: As we move towards the events in 2017, 2018, how do you

evaluate the role of Meles Zenawi, who when he came to power was

hailed as someone who was one of the renaissance leaders of Africa,

I think along with – perhaps it was Thabo Mbeki, I believe, and

maybe it was the other leader who was the country of Nigeria – was

hailed a renaissance leader. How was he seen inside the country?

Because he’s in power until the early 2000 period, I believe.

Checole: You’re right. In fact, in the 1990s, Museveni in Uganda,

Thabo Mbeki in South Africa, Paul Kagame in Rwanda, Isaias Afwerki

in Eritrea, and Meles Zenawi in Ethiopia were seen as the

renaissance force that are going to change the way Africa operates.

There was much hope put on them. (laughter) But that is more

idealism than realism. Meles did, in my opinion – I have a lot of

respect for him. He did a lot of good for the country. But he was

encumbered by the fact that he comes from a single party, the TPLF,

that was – like it or not, became a ruling party, and the leader of

the EPRDF, the group of parties that came together.

And he had several problems. One, he got into a war, once again,

with Eritrea in 1997, and that became disastrous. It became almost

genocidal. Hundreds of people, young people, died in that war. He

was not able to manage or to get himself out of that problem, and

it created quite a resentment among especially Ethiopians of

Eritrean origin who were expelled from the country, from Ethiopia.

The second, he created a federal constitution that relied heavily

on ethnic formation, that divided the country on the base of

ethnicity and gave certain amount of autonomy to those ethnic

states. That comes with its own problem, and it is so huge I can’t

even talk about it in a detailed manner. The Oromo people, who

always complained about oppression – rightly so – who always

complained about marginalization, woke up, rose up, and said things

have to change. The EPRDF had to respond, and within it, it had

fractures. And the party – this coalition party is still alive,

but it’s still being challenged by what has happened since.

Turner: It appears to be fairly clear, and you can update us on

that, Kassahun, that Hailemariam Desalegn, when he stepped down in

2018, that he stepped down because of the developments in the Oromo

region. Is that the whole story from your analysis? That appears

to be what he said, and that appears to be what many analysts say.

Checole: Well, from what I can read, I think Desalegn was a decent

person. He had a positive idea about how to work out the problems

that exist in Ethiopia. But he didn’t have much power within the

party. In other words, he really was almost like a symbolic

element, not having a genuine power or power base to change things.

So when the rise of the Oromo people, especially the young people

in Oromo – the rise of young people among the Amhara came up, he

saw that there’s not much he could do. He saw the writing on the

wall, and he stepped down. And I think he did it in a very

gracious and very humble way, which led again to Abiy Ahmed.

Turner: Now, Abiy Ahmed, he’s of Oromo origin, but he fought in

wars [for the previous government]. He worked in intelligence. He

holds a doctorate. The analysis is that there was some

contestation about him becoming the prime minister. How do you

evaluate that process from Desalegn to Abiy Ahmed?

Checole: Well, I know as much as you do about the evolution of

Abiy Ahmed. Yes, he was part of the ruling party. He was in the

intelligence, and he fought in the Eritrean War. So he comes from

a military background, from an intelligence background, and that

may help him a little bit in understanding what war means and the

negative role wars place in society. His origin, his ethnic

origin, is of mixed background. He’s Amhara partially. He’s Oromo

partially. But I’m hoping that he has gone beyond that to say that

he’s more of an Ethiopian than an ethnic this or ethnic that.

So far, he has done the best he can. He has shown idealism. He

has shown hope and aspirations for progress in the country. But

the challenges are incredible, Walter. The challenges are huge,

and how he manages this challenge, how he survives this challenge

is going to be the one that defines him properly. So his ethnicity

aside, I think he has his heart in the right place, but the reality

of Ethiopia is quite complex and quite difficult. I don’t envy

him.

Turner: How is he being received in Ethiopia? How has Abiy Ahmed

– because he’s come and he’s made some changes very quickly. He’s

moved on issues of political prisoners. He’s talked about

restructuring the state. Maybe the most important piece, I would

say, is the reconciliation, if that’s the word –

Checole: Yeah, absolutely, with Eritrea.

Turner: – with Eritrea. How has that been received?

Checole: I think the people of Ethiopia and Eritrea received this

reconciliation idea very well. They were tired of war. They were

tired of the standing still situation in both societies. So it was

a great joy to see the potential of peace – the ability of the two

people to live together in peace and progress jointly economically

and otherwise, and to visit societies that were divided between the

two borders. It was an emotional and very encouraging period.

As you said, he also made a very good move in terms of freeing

prisoners. Rightly or wrongly, thousands and thousands of people

were in prison for their political views and for other petty

crimes, and he made a really sweeping action to release prisoners.

The third most important role he played was to free the press, to

be able to say that people can speak freely their opinion, and

write about it and publish and speak on radio and TV, and that is a

major move. That really was quite encouraging for people as a

whole. I hope it holds. He seems to have backed out a little bit.

As of now, we have a few journalists in prison, and that is a sad

experience to see happen.

The fourth most important is his move on the economy. I think his

move to privatize state businesses, his move to allow businesses to

grow and prosper independently without the heavy intervention of

the state, is looked at very positively. And the list goes on and

on. There are several other good moves that he has made. Now the

challenge is how to keep it going.

Turner: The notion that you mentioned there of privatization –

looking at the debt that exists, I think, currently with the

country of China – I don’t remember, $26 billion debt to China –

and the increasing interest, not just in Ethiopia and Eritrea, in

the Horn of Africa and Africa altogether, the Saudis, the UAE, etc.

– are there some perils there in terms of being able to continue to

manage the economy to the best interest of the Ethiopian

population? Your thoughts?

Checole: Well, to be honest with you, I’m not an expert in

economics, but my view is the following. China is helping Ethiopia

to grow economically, particularly in the area of infrastructure,

which is much needed. The roads need to be built up. The

railroads, the airports, the ports of the country, both in

Ethiopia, Djibouti, Eritrea, and it’s very, very important role it

is playing.

One has to be responsible on how one takes aid, support, loan from

the Chinese. If you don’t receive this support carefully, then you

will be in trouble, as other African countries like Zambia are.

The Chinese are like any other capitalist society. They are

looking for their own interests, their own benefits. So balance

has to be found between your interests and that of the Chinese

economy and society.

So I don’t see it negatively. The loan doesn’t scare me as much.

As long as the economy is growing, as long as it’s managed properly

and corruption is kept under control, then I think the loan can be

adjusted, as they already have done with Abiy and the Chinese

government and dealt with properly.

Turner: How has this period of reconciliation, if we want to refer

to that – I’ll use that word, Kassahun – how has it impacted – what

have we seen in Eritrea under Isaias Afwerki? Obviously, it’s been

positive with people being able to be in touch with relatives and

being able to cross borders and reconciliation about land. There

certainly have been questions about the way in which the

relationship between Ethiopia and Eritrea has led Eritrea perhaps

to be involved in events in Somalia, perhaps to be used as a base

for some of the conflicts in Yemen. Give us your thoughts on how

Eritrea has moved through this last 18 months, year-plus.

Checole: Yeah, the Eritrean situation is a very difficult and

complex situation, mainly because of the revolutionary party in

power. It has not yet devolved into more civic government. We

still have the same revolutionaries who fought the war for

independence ruling the country. So their attitude and approach is

that of revolutionaries, and that is simply to say we have a goal,

we have a direction, we’re going to follow it at any cost, and

civil rights necessarily are not their priority. You see what I’m

saying? So what is their priority is that there’s discipline,

there is a clarity of direction, and that they are not imposed upon

by external forces, and that they keep the country independent.

So the reconciliation brought about hope, but it didn’t bring about

fundamental changes within Eritrea. So nothing in Eritrea has

really changed that we can talk about. It remains the same way it

has in the last 28 years of independence. And there are legal

issues that need to be resolved between Eritrea and Ethiopia. For

example, the Ethiopian Army is still occupying Eritrean land. They

need to withdraw. The argument that was reached between the two

countries in 2000, 2001 has not been implemented. That needs to be

done. The borders that were quickly opened when Abiy came to power

have now essentially closed down. That also needs to be sorted

out, because what people want is a free movement of people back and

forth and the free movement of the economy between the two

countries.

[Editor´s note: For an in-depth analysis of the flaws in

the peace process between Ethiopia and Eritrea, see the early 2019 analysis by Yohannes Woldemariam.]

So Eritrea, by and large, remains the same. It is steadfast in its

position that the sovereignty of the country is more critical than

civil rights. So we still have the same prisoners that have been

there for the last 15 years, the same leaders. The economy is

burdened by the sanctions that was implemented on Eritrea –

international sanctions. It’s burdened by the fact that there is

no investment from outside, and the government still has a

stronghold on the economy. And in my opinion, they haven’t done a

good job with it. So they need to relent. When they will do so is

a matter of time and something that we have to watch.

Turner: Kassahun, as your work informs you, you would certainly be

characterized – I think this is a fair judgement – as a pan-

Africanist. Looking at the continent and looking at the challenges

that are faced by the leadership of Museveni, the recent events in

Zimbabwe, the challenges in Nigeria and Burkina Faso and

particularly northern Africa at this point, should we have more

patience with seeing what Abiy Ahmed is doing, how it plays out

both in Ethiopia and Eritrea? Because at this point, there’s even

some levels of concern and criticism from people who are Tigrayan,

who are saying, well, things are not turning out well. This is

changing the face of the EPRDF. As a pan-Africanist, putting this

in the context of how do we keep going forward for Africa, your

thinking on that?

Checole: Well, thank you for raising this issue, because pan-

Africanism is the closest thing to my heart than anything else.

The long-term solution for Africa is a united Africa. There is no

other alternative. We were divided and put apart because of

colonial structures with no consideration to our linguistic,

geographic, and cultural unity. That still remains a problem, and

no one can solve that but us. Africans can resolve it by saying

that the colonial structure is unfair and unnecessary, and we need

to create a unitary system of some kind in Africa. That move has

already started, and it’s making progress. Very slowly, of course,

but it is making progress. Soon we will have potentially a single

currency, a single passport, a united economic structure that

allows people to move back and forth with their goods and their

services. So all of those are happening, but in a slow manner.

Now what we need to deal is with regional issues. For example, in

east Africa, Abiy brought the hope that we can have a regional

union. That makes Djibouti, Somalia, Eritrea, Ethiopia, the Sudan,

and even Kenya. They can form a union, as used to be in the East

African Community. This union can lead into other unions of

regions coming together. It is a big challenge. We don’t need to

change the state structures. But we need to have an umbrella body

that coordinates our economic and social development in the area.

So I am hopeful that pan-Africanism, hopefully in our lifetime,

will be advancing faster than it has so far. But it’s the only

solution that I can see to our political and social problems and

our economic dependency on China and others.

Turner: OK, because I think that’s the other analysis – and one of

the articles you shared with me is this discussion about the fact

that there’s a half a million Ethiopian workers who are in Saudi

Arabia, another 100,000-plus – it seems as if both Turkey and Qatar

and the Saudis and the UAE have their interest not just in Ethiopia

and Eritrea, but also throughout the African continent. It seems

as if Abiy has been very, very active. In fact, was the

reconciliation – did it not occur in Saudi Arabia? Am I mistaken?

Checole: Yeah, the formal presentation of the reconciliation

document happened in Saudi Arabia. Let me tell you about our so-

called Arab neighbors. They are a blessing and a curse at the same

time – a blessing because they have a huge amount of resources that

if properly managed, if properly shared among the peoples of the

area, can become an incentive to growth that will not only benefit

them, but benefits the peoples of the Horn of Africa. Right now,

that is not happening. Both UAE and Saudi Arabia are engaged in a

war in Yemen, which for all practical purposes is an African

country, except that it’s divided by water. They have done

incredible amount of damage to that society. It’s a totally

unnecessary war. I think even UAE is beginning to regret its

involvement in it. So that is a blessing yet to be shared that

they have the resources to make a difference in the area.

The curse factor is that they see themselves as superior to other

peoples in the area. And that cultural nuance is critical, because

as they have done in the slavery period by enslaving Africans, they

continue to have an attitude that these Habesha, these black

people, do not have anything to offer to them. Yet if you go to

any of these countries, you will see that a large amount of the

workforce is drawn from people of color from either Africa or Asia.

And their attitude to this labor is horrendously unfair. They

underpay them. They overwork them and maltreat them when they have

to exit out of the country.

So I say this in both ways. Their existence and their relative

wealth is both a blessing and a curse. And more dialogue, more

discussion is to be done, from an African point of view, with these

Arab nations – particularly the ones on the Gulf area, who for all

practical purposes are also Africans. All you have to do is look

up their genesis and look up their intermarriage from Kuwait to

Qatar to Oman and all these places. Their link with Africa is deep

and long, but they are slow in recognizing it and slow in acting on

it.

Turner: The Ethiopia-Eritrean diaspora, Kassahun, their thoughts

from – you’re here. You work here. I know you’re a global person.

The thoughts of Ethiopians and Eritreans in diaspora – how do they

see these recent developments with Abiy Ahmed and this last more

than a year or so of changes and new pronouncements?

Checole: Walter, like all diaspora movements, diaspora is always

critical in helping the home countries, and also in damaging the

home countries, in the sense that they are so ideologically

divided, organizationally divided. They in many ways sometimes

bring trouble to home countries than they do positive things. Now,

we have to admit that the remittances to Eritrea and Ethiopia are

critical. It is a significant part of the economic situation in

both countries. And obviously, the way our societies are built up,

we believe and drive our lives in supporting our families and

relatives in the home country. So the remittances will continue,

and it makes a significant difference in the home economies.

But the ideological division that the diaspora leaves – for

example, among Eritreans, there are people who are excited and

hopeful by the new dispensation. The others will say, well, Isaias

Afwerki is about to sell out the country to Ethiopia. We fought

all these years to be independent, and now he wants to make us part

of Ethiopia. I don’t think that is true. I don’t think Isaias or

any other leader in Eritrea wants to give up on the sovereignty of

Eritrea, but that’s the feeling. It’s a very strong feeling. How

to allay it is another issue.

Among Ethiopians, the ethnic division that exists in Ethiopia also

exists among the diaspora, and that is a very bad situation. They

have not managed to come together as Ethiopians. They are still

functioning as Tigrayans, Amharas, Oromos, what have you, and this

has a negative role to play in the home country. So the diaspora –

in all their love for the home country, they often forget that they

have moved on, and they have a society, whether they’re living in

Europe or the United States, of their own making, and they should

be engaged strongly in local society, but they are still

intervening in the home politics and economy and society.

Turner: Although, from, I guess, the read of those of us here who

work around African issues or in general populations concerned with

human rights, it appears to be that the ascension of Abiy Ahmed and

what he’s been able to do or what he’s been able to imagine or

dream that he would do, it would seem to be a positive for all of

the African continent, for African Americans, for Africans

throughout the diaspora. Certainly not a smooth road, but it

appears to be a way forward.

Checole: Yes, there is no question about it. I think Africa as a

whole has benefited from the relationship with the diaspora – the

traditional diaspora, the enslaved Africans who were forced to come

to this land, and it should be playing a significant role in

African development. And they had in the liberation. Whether you

are in South Africa or in Ethiopia, the role of the diaspora, the

traditional diaspora, the enslaved Africans who came here

involuntary, has been important, has been influential in many ways.

It should be more. And the African Union should open up

citizenship, for example, on the African diaspora and allow the

economy to grow through their intervention.

But the new diaspora, the people like me who came in the last four

or five decades, have a critical role to play. One, we should

really play a significant role in the African American community.

As a publisher, I wouldn’t be what I am if I hadn’t relied on the

existence of the African American community and my linkage with it

– I have to say I would not have survived the last 36 years

without that support system. And it’s very important to realize

the linkages in that sense. But we have to humble ourselves. Most

Africans of recent migration have an attitude towards African

Americans which is negative, and that has to change. They need to

study the history. They need to study the role of African

Americans in the society and appreciate and play a significant role

in that sense.

Turner: We certainly appreciate the work that you’ve done,

Kassahun, with both Africa World Press and the Red Sea Press.

That’s who we’re speaking with today. Can you give us a website

here as we finish up so that people can go online and take a look

at the amazing list of titles that you have, Kassahun? What is the

website?

Checole: Indeed. It is

http://www.africaworldpressbooks.com.

Turner: Any last words here in our last moment?

Checole: I just want to say the following – that hope is

essential, and what Abiy gave us in east Africa is hope. I wish

him great fortune, great opportunity to get to the point where we

all begin to realize a united east Africa, a united Horn of Africa

– that would be critical. And as I said in my last point, but it’s

also important for particularly the African American community to

intervene positively in Africa by going and spending their

resources, understanding the culture, and playing an influential

role in African economic development.

Turner: Kassahun, it’s always a total pleasure. I encourage

people to go to African World Press Books and take a look at the

work that you’re doing. I think anything that anyone is looking

for, that you can find it on your site. Much respect for the work

that you’ve done for so many years. And please stay in touch,

Kassahun. You’re always welcome on Africa Today.

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication

providing reposted commentary and analysis on African issues, with

a particular focus on U.S. and international policies. AfricaFocus

Bulletin is edited by William Minter.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please

write to this address to suggest material for inclusion. For more

information about reposted material, please contact directly the

original source mentioned. For a full archive and other resources,

see http://www.africafocus.org

|