|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

Africa/Global: #MauritiusLeaks Reveals Tax Dodges

AfricaFocus Bulletin

August 12, 2019 (2019-08-12)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

“Based on a cache of 200,000 confidential records from the

Mauritius office of the Bermuda-based offshore law firm Conyers

Dill & Pearman, the investigation reveals how a sophisticated

financial system based on the island is designed to divert tax

revenue from poor nations back to the coffers of Western

corporations and African oligarchs, with Mauritius getting a share.

The files date from the early 1990s to 2017.” - International

Consortium of Investigative Journalists

Despite involving at least two large U.S. companies with worldwide

interests, this new set of revelations from the group that broke the

Panama Papers in 2016 has had hardly any coverage in the United

States, with no mention to date in the New York Times, Washington

Post, or Wall Street Journal. Worldwide it has apparently had significant coverage primarily

in East Africa and India. But it is a significant case study in

how the international tax avoidance system works, particularly with

reference to Africa. AfricaFocus Bulletin is accordingly publishing

two Bulletins today, one capsulizing the news from ICIJ, and the

other looking more deeply at the policy implications, including a

profile of Aircastle, based in Stamford, Connecticut, a leading

provider of leased airplanes to airlines around the world.

This AfricaFocus Bulletin contains excerpts from the principal

article launching the reporting on the Mauritius Links

investigation.

Other articles published to date include a profile of the law firm

involved, a case study of an

American-owned company specializing in luxury vacation resorts and

hotels around the world, and a report on the reaction to the investigation in a number of

the countries involved.

The other AfricaFocus sent out today, available on the web at

http://www.africafocus.org/docs19/iff1908b.php, and entitled

"Tax Avoidance 101," includes brief background on the

investigation, a profile of Aircastle compiled by AfricaFocus based

on material from ICIJ and Quartz as well as additional research,

and a summary by Tax Justice Network of the significance of the

Mauritius material for global action to counter tax avoidance.

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on tax justice and illicit

financial flows, visit

http://www.africafocus.org/intro-iff.php

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Break from Publication

Note to readers: AfricaFocus Bulletin will be taking a break from

publication for a few weeks, resuming in early to mid-September.

The AfricaFocus website and Facebook pages will continue to be

updated during the break.

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

International Consortium of Investigative Journalists

July 23, 2019

[Excerpts only. For full story and many related resources, visit

https://www.icij.org/investigations/mauritius-leaks/]

Bob Geldof’s firm wanted to buy a chicken farm in Uganda, one of

the poorest countries on earth. But first, an errand.

After soaring to fame in the 1980s for organizing Live Aid and other anti-famine

efforts, the former Boomtown Rats rocker had shifted to the high-

powered world of international finance. He founded a U.K.-based

private equity firm that aimed to generate a 20% return by buying

stakes in African businesses, according to a memorandum from an

investor.

The fund’s investments would all be on the African continent. Yet

its London-based legal advisers asked that one of its headquarters

be set up more than 2,000 miles away on Mauritius, according to a

new trove of leaked documents.

The tiny Indian Ocean island has become a destination for the rich

and powerful to avoid taxes with discretion and a financial

powerhouse in its own right.

One of the discussion points in the firm’s decision: “tax reasons,”

according to the email sent from London lawyers to Mauritius.

Geldof’s investment firm won Mauritius government approval to take

advantage of obscure international agreements that allow companies

to pay rock-bottom tax rates on the island tax haven and less to

the desperately poor African nations where the companies do

business.

“One little wad of cash can be the difference between a poor

country building big infrastructure or not,” a Ugandan tax official

told ICIJ.

Another benefit of a headquarters on Mauritius: opacity.

Transactions to and from Mauritius to local units – that can have

huge impacts on tax liability – are tucked away in confidential

financial reports filed on the island.

The Mauritian newspaper L´Express was the key local partner in

this investigation by ICIJ. Credit: L´Express.

A spokesman for Geldof’s firm, 8 Miles LLP, said its investors

include international development finance institutions that

“request that we consolidate their funds in a safe African

financial jurisdiction for onward investment into the various

target African countries. Because of its reputation, Mauritius is

used by many private equity investors for this purpose.”

The spokesman said the firm’s African investments follow high

standards “to create jobs, improve communities…and by generating

increasing tax revenues which support the governments where we

operate.” The spokesman said, “Only when we sell a company will

the sale proceeds be paid back into the fund in Mauritius.”

Geldof declined to comment.

Mauritius Leaks, a new investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative

Journalists and 54 journalists from 18 countries,

provides an inside look at how the former French colony has

transformed itself into a thriving financial center, at least

partly at the expense of its African neighbors and other less-

developed countries. In Uganda, more than 40% of the population

lives on less than $2 a day.

Based on a cache of 200,000 confidential records from the Mauritius

office of the Bermuda-based offshore law firm Conyers Dill &

Pearman, the investigation reveals how a sophisticated financial

system based on the island is designed to divert tax revenue from

poor nations back to the coffers of Western corporations and

African oligarchs, with Mauritius getting a share. The files date

from the early 1990s to 2017.

The island, which sells itself as a “gateway” for corporations to the

developing world, has two main selling points: bargain-basement tax

rates and, crucially, a battery of “tax treaties” with 46 mostly

poorer countries. Pushed by Western financial institutions in the

1990s, the treaties have proved a boon for Western corporations,

their legal and financial advisers, and Mauritius itself — and a

disaster for most of the countries that are its treaty partners.

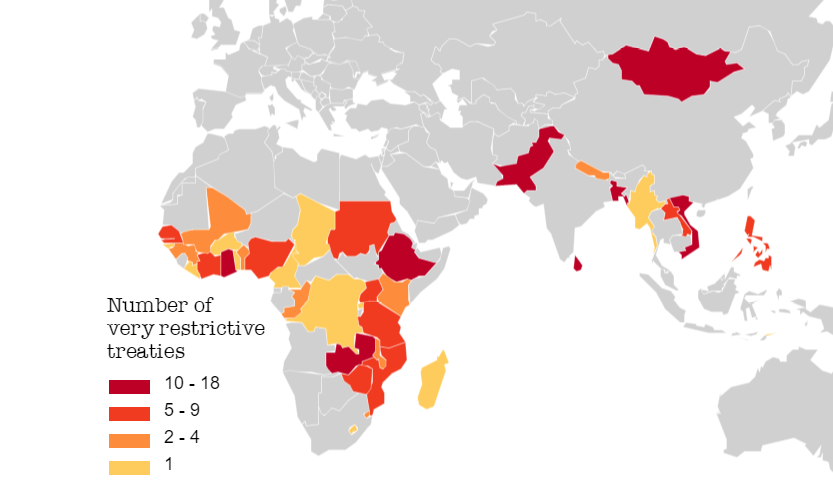

This map, from

research in 2017 by ActionAid, shows countries in Africa

and Asia that have signed very restrictive tax treaties with other

countries such as Mauritius, limiting their ability to tax

corporations based in the partner countries.

“What Mauritius is providing is not a gateway but a getaway car for

unscrupulous corporations dodging their tax obligations,” said

Alvin Mosioma, executive director of the nonprofit Tax Justice

Network Africa.

The leaked records – including emails, contracts, meeting notes and

audio recordings – provide a glimpse inside a busy offshore law

firm working with global accounting and advisory firms for some of

the world’s largest corporations and some very wealthy individuals.

They’ve all found their way to an island built on helping the rich

avoid paying taxes to nations as far-flung as the United States,

Thailand, and Oman.

Mauritius’ minister of financial services of good governance

Dharmendar Sesungkur, who oversees the country’s offshore sector,

said that ICIJ’s

information was “outdated.” The minister said that independent

organizations, including the World Bank, recognize that “Mauritius

is a cooperative and clean jurisdiction that has made significant

progress in adhering to international standards.” [Read the

Government of Mauritius’ full response]

Mauritius has introduced “major policy (as well as legislative)

changes,” Sesungkur said. Prime Minister Pravind K Jugnauth

recently announced tighter rules for companies that want to benefit

from the island’s low tax rates; such companies must have greater

control and activity in Mauritius and more skilled employees.

…

From sugarcane to shell companies

A longtime possession of the Dutch, French and then the British,

Mauritius was for centuries a poor agrarian society with an economy

based mostly on sugarcane. Its economic prospects seemed forever

limited by its location, 1,250 miles east of the African coast, and

tiny size, smaller than Rhode Island.

Then in the early 1990s, Rama Sithanen pushed an idea.

The Mauritius finance minister at the time, Sithanen observed that

Luxembourg, Switzerland, Hong Kong and other, more obscure

jurisdictions had grown into financial powerhouses by serving as

low-tax gateways to wealthy nations nearby. He said Mauritius

should do something similar, offering itself as a stable,

corruption-free bridge to Africa and other less developed regions.

“The potential exists to explore new avenues and to look for new

markets,” he argued before the Mauritius Parliament in 1992,

pushing a bill that would make possible the island’s first shell

companies and allow some firms to pay zero taxes on profits and

capital gains. One parliamentary colleague called the bill “a

wonderful tax tool.”

An opposition member objected, saying the bill would create at

least the appearance that Mauritius was benefiting at the expense

of poorer neighbors.

“It is a tough world,” retorted another government minister in

support of the law. “We cannot waste time.”

Within weeks of the bill’s passage, Mauritius officials were off on

marketing trips to Asia. In the law’s first year, 10 offshore

companies incorporated in Mauritius. Two years later, that number

had passed 2,400.

Tax treaties proliferate

A key part of the island’s strategy: tax treaties, lots of them.

Starting back in the 1920s, “double taxation agreements” were

adopted to protect businesses with international operations from

being taxed twice for the same transaction. Two nations simply

agreed on dividing one set of taxes between them. To encourage

investment, tax treaties also limited the tax rate governments

could apply to certain cross-border transactions.

Tax treaties surged as global trade blossomed after World War II; a

second wave came during decolonizations in the 1960s and 1970s.

Under the umbrella of the Western-dominated Organization for Economic Cooperation and

Development, richer countries pushed for treaties that

awarded most of the tax revenue to themselves, not the poorer

countries where the business activity took place.

Officials in some developing countries sensed early on that the

system was tilted against them. Among their complaints: Western

companies were shifting income out of developing countries by

inflating “expenses” and “fees” paid to the home office, reducing

local taxable income. “They have taken out of Zambia every ngwee

[penny]” owed in taxes, Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda fumed

in 1973.

Developing countries believed they had to enter into treaties to

attract foreign investment, even if it meant signing away tax

revenue that could fund education, health care and other vital

government services.

Aid from poor to rich

By 1974, an academic paper was already warning that the treaties in effect represented “aid

in reverse – from poor to rich countries.”

Nonetheless, the number of treaties surged again in the 1990s as

Western corporations and their advocates within international

institutions pushed them as a requirement for attracting foreign

investment. Meanwhile, tax havens, seeing an opportunity, dropped

their tax rates, encouraged corporations to set up shell

“headquarters” in their countries, and promoted tax treaties as a

way to avoid paying taxes.

For Mauritius, a big breakthrough came in the early 1990s when an

enterprising lawyer in Mumbai discovered that a then-dormant 1982

India-Mauritius tax treaty would allow his Western clients to avoid

paying taxes in both the United States and India. Western money

poured into the newly liberalized Indian market – after first

passing through Mauritius.

“Success has many fathers,” said the lawyer, Nishith Desai, in an

interview with ICIJ. “People didn’t even know where Mauritius was

located. People mixed things up between Mauritius, Maldives, Malta

. . . a lot of small islands starting with the letter ‘M.’ ”

Gushing press releases and news articles suggested that Mauritius

was on a path to becoming the Hong Kong or Singapore of the Indian

Ocean. “We avoid stacks of tax,” one fund manager told Toronto’s

Financial Post in 1994.

Mauritius introduced a flat corporate income tax rate of 15% with

foreign tax credits that can drive that down to an effective rate

of 3%. Mauritius rolled out Global Business Licence 1, which

allows companies with operations elsewhere to be “resident” in

Mauritius for tax purposes and pay its low rates. It went on to

sign dozens of tax treaties with countries around the world,

including 15 in sub-Saharan

Africa.

…

Poorer countries push back

Some countries have tried fighting back – but it’s not easy.

Renegotiations can take years. Political leaders often seek to

avoid the diplomatic fallout.

South Africa signed a new treaty with Mauritius, which first

ignored South Africa’s requests to modify the 1997 text and then

resisted for years, according to people involved. Western

corporations lobbied the South African parliament to reject the

renegotiation and threatened to move their offshore operations to

Dubai. The new treaty took effect in 2015.

“The old treaty basically gave the store away,” said Lutando Mvovo,

a former South African treasury official who took part in the

negotiations.

Successive Indian governments for years challenged the legality of

the Mauritius 1982 treaty. And they kept losing. In a landmark 2012

case, India’s Supreme Court held that the tax office could not

question U.K. telecom giant Vodafone’s $11 billion acquisition of

an Indian rival through a Mauritius company. The decision cost

India $2.2 billion in lost tax revenue.

It took 20 rounds of negotiations over 20 years for India to prod

Mauritius in 2016 to remove the abusive provisions of the original

1982 treaty, one Indian official told ICIJ.

In separate interviews with ICIJ, tax officials in Egypt, Senegal,

Uganda, Lesotho, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Thailand, India, Tunisia

and Zambia all said their treaties with Mauritius were crippling.

“Personally, we regret signing the treaty,” said Setsoto Ranthocha,

an official with the Lesotho Revenue Authority, now involved in a

renegotiation effort. Lesotho’s treaty with Mauritius dates to

1997.

“The companies are the winners,” Ranthocha said. “It makes me go

mad.”

Namibia is reviewing its treaty with Mauritius, officials told ICIJ

partner The Namibian. In March, Kenya’s high court struck down that

country’s treaty with Mauritius for technical reasons. Tax Justice

Network Africa filed the complaint, arguing that the treaty would

allow companies to abusively “siphon” money out of Kenya. In June,

Senegal announced that it would seek to cancel its tax treaty with Mauritius, claiming that

the agreement cost it $257 million over 17 years.

“It is the most unequal treaty for Senegal of all the treaties we

have signed,” Magueye Boye, a tax inspector and Senegal’s lead

treaty negotiator, told ICIJ. It is an “enormous pipeline for tax

avoidance,” he said.

Another country reviewing its treaty with Mauritius is Uganda.

…

‘No nefarious agenda’

Mauritius’ tax benefits are popular with African elites as well as

foreign ones.

Patrick Bitature owns telecommunications, energy, media and hotel

companies across Uganda. One of Uganda’s richest men, who once sat

on the boards of one-third of the companies on the Kampala Stock

Exchange, Bitature has been close to Uganda’s authoritarian

president, Yoweri Museveni, according to The Indian Ocean

Newsletter, a respected news outlet.

He is also majority owner of Electro-Maxx, which runs Uganda’s

largest thermal power plant, located in the eastern town of Tororo.

It is the first African-owned and financed company to produce power

on the continent.

In 2011, the investment company African Frontier Capital LLC

proposed a $17.5 million investment in Electro-Maxx that passed

through a newly incorporated Mauritius company named African

Frontier I LLC, according to minutes of the African Frontier board. The proposal included a $2.5 million personal loan to

Bitature, the minutes say.

The company’s minutes, dated June 2011, also said it would apply

for a tax residency certificate every year to “benefit” from the

tax treaty between Uganda and Mauritius.

Robert Mwanyumba, a tax researcher focused on East Africa, said

that if the company used the treaty with Mauritius, it would have

been subject to its low corporate income tax rate instead of

Uganda’s 30% rate.

Bitature confirmed the existence of a “bona fide” transaction and

said the use of a tax treaty was a question for African Frontier,

which did not provide a comment on the subject.

Responding to ICIJ media partner The Daily Monitor, Bitature said

that Electro-Maxx sought external financing when it could not raise

money for a new project. “The transaction was carried out within

the provisions of the tax laws and fully accounted for in tax

returns shared with” the Uganda Revenue Authority, he said.

“All taxes if any” were paid, Bitature said, adding “there was

absolutely no nefarious agenda.”

African Frontier Capital, via the Mauritius company African

Frontier I, ended its investment in Electro-Maxx in 2014. It told

ICIJ that the investment was “a completely arms-length transaction”

that fully complied with the laws of the countries involved.

Under pressure

In January [2019], after years of complaints from its treaty

partners and under pressure from international institutions,

Mauritius overhauled the tax laws governing its offshore sector.

Gone is Global Business License 1, the form of shell company that

poorer nations denounced as an exploitative tax-avoidance tool.

Mauritius now requires investors to have reasonable local staffing

and to spend money on the island that reflects the activities of a

real office – known as “enhanced substance” – to benefit from tax

treaties or low tax rates. Shell companies are a thing of the past,

Mauritius assures outsiders.

Bemoaning the new rules, one member of Parliament blamed the Panama

Papers and Paradise

Papers investigations by ICIJ, among other

exposés, for soiling the offshore industry’s reputation. “Under

pressure from the OECD and the European Union, who have at heart

only their interest to further tax their citizens and corporations,

Mauritius, once again, has kowtowed,” lawmaker Mohammad Reza Cassam

Uteem said.

Corporations, fund managers and tax advisers warned the changes

would make Mauritius less attractive for investment.

Others, however, suggest that its reforms may be little more than

box-checking designed to keep the country off international

blacklists. Mauritius, they say, has already found ways to continue

providing tax-avoidance opportunities.

The island reluctantly agreed, for example, to a rule that allows a

Mauritius treaty partner to deny tax-treaty benefits to a

multinational corporation that opens in Mauritius with the

“principal purpose” of exploiting those benefits. Experts say that

poorer countries will rarely be able to make use of that provision:

Denying treaty benefits to a corporation will require technical,

financial and political resources that a developing country may not

have.

Sol Picciotto, emeritus professor at Lancaster University law

school in England, said of Mauritius: “They play the game so as not

to be denounced as uncooperative, but they can maneuver within the

grey areas of the rules. They can say they’re doing it by the book,

but the book is full of technical tricks, and Mauritius has some

very skilled technicians.”

This year, Setsoto Ranthocha, the Lesotho tax official, negotiated

with Mauritius to fix a treaty that he says has cost his country

dearly. “They are tough negotiators,” Ranthocha said of his

Mauritius counterparts. “They know what they are doing.”

Meanwhile, Mauritius is pursuing new treaties with 16 African

states, bidding to bring its coverage to nearly 60% of the

continent.

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication

providing reposted commentary and analysis on African issues, with

a particular focus on U.S. and international policies. AfricaFocus

Bulletin is edited by William Minter.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please

write to this address to suggest material for inclusion. For more

information about reposted material, please contact directly the

original source mentioned. For a full archive and other resources,

see http://www.africafocus.org

|