|

Algeria

Angola

Benin

Botswana

Burkina Faso

Burundi

Cameroon

Cape Verde

Central Afr. Rep.

Chad

Comoros

Congo (Brazzaville)

Congo (Kinshasa)

Côte d'Ivoire

Djibouti

Egypt

Equatorial Guinea

Eritrea

Ethiopia

Gabon

Gambia

Ghana

Guinea

Guinea-Bissau

Kenya

Lesotho

Liberia

Libya

Madagascar

Malawi

Mali

Mauritania

Mauritius

Morocco

Mozambique

Namibia

Niger

Nigeria

Rwanda

São Tomé

Senegal

Seychelles

Sierra Leone

Somalia

South Africa

South Sudan

Sudan

Swaziland

Tanzania

Togo

Tunisia

Uganda

Western Sahara

Zambia

Zimbabwe

|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

USA/Africa: At Home in Maine

AfricaFocus Bulletin

November 25, 2019 (2019-11-25)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

“Safiya overcame so many obstacles, I can’t find the words to

describe how much we’re proud of her. Internet trolls could not

stop her, threats could not stop her. She’s the perspective the

city needs. It’s a really big deal, a tremendous transformation for

this city.” - Mo Khalid, speaking of his sister Safiya Khalid on

her election to the Lewiston, Maine City Council on November 6,

2019

If you´re not from Maine, but have heard of Lewiston in the news in

recent years, it may be because of the Lewiston High School boys´

soccer team on which Mo Khalid played, which has won 3 state-wide

championships in the last five years (2015, 2017, and 2018, but not

this year). Or it may be from the many articles over the years that

have noted the welcome, despite difficulties, for African refugees

in Lewiston in the past two decades.

Two authors who have closely followed Lewiston for most of this

period, Amy Bass and Cynthia Anderson, have recently published

books which well complement each other and provide engagingly

written and well-researched accounts of the encounters between

Lewiston and its new residents. Bass, in One Goal,

highlights the story of the soccer team in the years leading up to

their first state championship in 2015, and how the school, its

soccer coach, and both immigrants and long-time residents fostered

school and community pride in a team led by African players.

Anderson, in Home Now, follows a set of immigrant and

other Lewiston residents over the years from 2016 to early 2019,

coping with anti-immigrant sentiments mobilized at national and

state level as well as local fears, and how sustained personal

interactions built the grounds for mutual understandings.

With a population of 36,000 in 2017, Lewiston is the second-largest

city in Maine, after Portland with 67,000. And, of all U.S. states,

Maine is the one with the highest percentage white population

(94%). Lewiston might seem to be an unlikely location to host as

many as 6,000 first or second-generation African immigrants, most

of them U.S. citizens. But most residents agree that both Lewiston

and Portland (with a larger African immigrant community although

proportionately less) have benefited from the new residents.

Lewiston in particular has experienced a significant demographic

and economic recovery. It has set a precedent that is being closely

watched at state-level, as Maine also is the

state with the highest median age and a recognized need for a

younger work force.

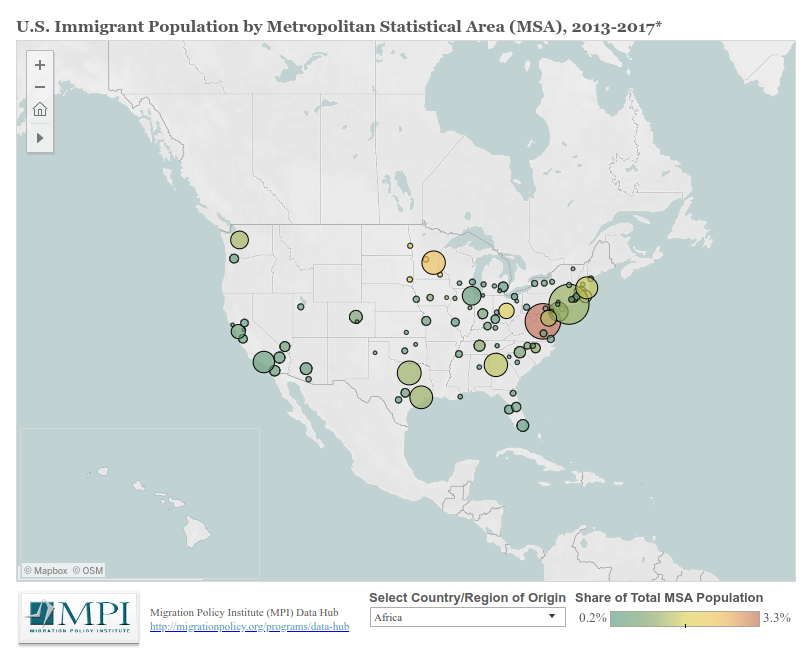

Lewiston differs in many respects from the hundreds of other

communities where African immigrants live across the country. It is

not among the top five or even the top 50 in terms of numbers of

African immigrants. According to census data, about 36 percent of the 2 million first-generation African immigrants live in the five metropolitan areas

of New York, Washington, DC, Minneapolis, Dallas, and Atlanta.

The proportion of refugees in the immigrant community in Lewiston

who were eligible for initial assistance is probably larger than in

most other communities. And each geographical area has its own

distinct mix of national backgrounds, such as the prominence of

Somalis in this immigrant generation and French-Canadians in

previous generations in Lewiston.

But one conclusion from these two authors is likely to hold nation-

wide. When I asked her about the election of Safiya Khalid, Cynthia

Anderson told me that again and again she found that “the most

vocal anti-Muslim and anti-refugee voices in the state belonged to

those who neither live among nor know newcomers.” And Amy Bass,

reflecting on her experience covering games of the Lewiston soccer

team around the state, similarly noted that contact through sports

provided an opportunity for changing minds, despite the hostility

often initially apparent among the supporters of opposing teams.

This AfricaFocus Bulletin contains, first, a recent article by Amy

Bass, on the election of the first Somali-American member of the

Lewiston city council, and a short excerpt from the book by Cynthia

Anderson. (Longer excerpts from Bass´s and Anderson´s books are

available on line in Sports Illustrated

and the Christian Science Monitor

respectively.)

These are followed by a short email interview with both authors

asking their reflections on developments since their books were

written. At the end of the Bulletin is a a selection of links to

other recent sources with additional relevant background

information, both about the particular Maine experience and the

wider context of recent African immigration to the United States.

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on migration, visit

http://www.africafocus.org/migrexp.php

On African refugees and Lewiston Maine also see the 2016 book

by Catherine Besteman,

Making Refuge:

Somali Bantu Refugees and Lewiston.

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

When Lewiston Wins...

by Amy Bass

https://www.amybass.net

November 6, 2019

https://www.amybass.net/post/when-lewiston-wins

I love Election Day. I always have. To be able to vote,

understanding what so many people have done before me to make sure

I can and to make sure others can too is something that I am in awe

of every single time I do it. Election Day morning is filled with

hope. Election Day evening can be exhausting, exhilarating, or

bone-crushingly sad and disappointing.

This year, Election Day was something extra special.

I woke up thinking not of voting, but of soccer. The Lewiston Blue

Devils Boys Soccer team was to face the Brunswick Dragons for the

regional title. The winner would go on to states. The loser would,

well, you know -- go home. Game day proved to be kind of miserable,

defined by the cold and rainy weather that often permeates playoff

soccer in Maine. But when the clock hit zero, Lewiston prevailed,

3-1, with Suab Nur and Bilal Hersi scoring goals backed by the

offensive and defensive skills of both the starting lineup and the

bench. Hunched over my phone with my daughter watching the postgame

celebration via proud sister Halima Hersi's Instagram live feed,

wearing the "I VOTED!" stickers we had received hours before at the

polls (and thank you to the kind poll workers who gave the 12-year-

old a sticker), I felt the familiar sense of awe that I get when

Lewiston plays soccer. It is a feeling that has never gone away, no

matter how many times I see them play. Lewiston, it seems, can’t

stop winning. But the day was far from over.

I first met Safiya Khalid on the sideline of – what else? – a

soccer game in Connecticut. Her brother, Mohamed, having graduated

from Lewiston High School in 2016, a member of the stories

championship squad described in ONE GOAL, was on the field for the

Kent School, where he and Abdi H. were spending a postgraduate year

playing soccer and preparing for college. It was a gorgeous fall

day, quintessential New England, and Safiya and younger brother

Sharmarke cheered Mo while goofing around with the various cousins

who had accompanied them on the trek. Later, over pizza, Safiya

told me about her life, about how she balanced work with school,

and regaled me with hilarious tales about her brothers.

Now, just 23-years-old, she is the first ever Somali-American

elected to Lewiston City Council.

She nailed down almost 70% of the vote, and she worked for it. She

campaigned in person, emphasizing door-to-door canvassing over

social media, where trolls loomed large and ugly. She introduced

herself to hundreds of people, telling them her story, how she got

from the refugee camps of Kenya to the United States. How she

majored in psychology at the University of Southern Maine while

working full time to help support her family. How she

unsuccessfully ran for school board when she was just 20-years-old.

And why she wanted Lewiston's elected officials to better represent

the diversity that now rings throughout the city, with thousands of

newcomers from Africa settling down, going to school, raising their

families, and trying to create a future. There are more young

people in Androscoggin County than anywhere else in Maine, the

"oldest" state in the U.S. Safiya wanted to get her voice into the

mix.

When I reached out to Mo, who has become a close friend, early in

the afternoon on Election Day to wish the family luck, he replied

with a photo of himself and his friends -- soccer players, of

course -- still canvassing for his sister, getting out every last

vote they could. It would be several more hours before he would

text again, but when he did, the unofficial results were in.

"She wonnnnnh!!!!" read the text.

Nothing else needed to be said.

Despite a lot of ugliness, including and especially the racist and

xenophobic trolls who infiltrated her social media spaces (and some

of my own), Safiya Khalid had done it. She won. Endorsed by just

about everyone, surrounded by supporters and helpers, Safiya Khalid

mobilized a historic door-to-door campaign for City Council that

brought with it a huge victory.

I asked Mo this morning how he felt about all this, how he felt

about his sister achieving what she did. He replied:

Safiya overcame so many obstacles, I can’t find the words to

describe how much we’re proud of her. Internet trolls could not

stop her, threats could not stop her. She’s the perspective the

city needs. It’s a really big deal, a tremendous transformation for

this city.

Lewiston is a city that has experienced a lot of transformation in

a very short period of time. An influx of newcomers over the last

decade and a half, downtown's ongoing rebirth, the expansion of the

high school's athletic fields, the building of a new elementary

school, and now a referendum voted just yesterday by an

overwhelming margin that authorizes how the high school itself will

be bigger before too long.

And there is soccer, of course, which has become one of the

constants in this ever-changing city. On Saturday, the Lewiston

Blue Devils Boys Soccer team will head back to the state final

looking for a third straight title, and a fourth in five years. I

hope the Falmouth Yachtsmen are ready. Because when Lewiston wins,

American wins.

************************************************

Making Community

by Cynthia Anderson

https://cbanderson.net/

Excerpt from Chapter 13 in Home Now (2019)

New immigrants work throughout L-A [Lewiston-Auburn]—in both of the

hospitals, Argo, Bates College, the cities’ banks and hotels,

manufacturing plants, Walmart, supermarkets, and as childcare

providers, shopkeepers, farmers, caseworkers, home health aides.

Anti-Islamists claim that refugees and asylum seekers take jobs

that should go to native-born citizens. But Maine needs workers. It

still has the highest median age of any state—and labor shortages

in several sectors, including agriculture, hospitality, and retail.

For years Maine’s innkeepers and restaurant owners have imported

workers on H-2B visas to fill summer jobs.

According to Phil Nadeau, by late 2002 close to half of Lewiston’s

adult Somalis had found jobs. As more refugees arrived, that

percentage remained steady for years before rising at the end of

the decade. Early news stories reported employers reluctant to hire

Somalis because of concerns about Muslim culture. But by 2007, when

I wrote a magazine piece about Lewiston, things were changing. I

profiled Mohamed Maalin, who worked on the manufacturing floor at

Dingley Press. If he needed to pray during a shift, a crewmate

covered for him. “It’s worked out,” a manager said. “He’s a great

employee.” Last summer, driving west on Route 196 into Lewiston, I

noticed Dingley had a recruiting table set up outdoors. It was

there for days. One afternoon I saw a van pull up. Two black men

got out, walked toward the table. The company’s workforce is now 20

percent Somali and other African newcomers.

The availability of workers in the L-A area has drawn employers.

L.L. Bean opened a new boot-making plant in Lewiston in June 2017.

“Demographics are definitely part of it,” says Bean shift manager

Rick Valentine. “We wanted to feel confident we could fill the

jobs.” In some cases, Bean also receives tax credits for hiring

refugees.

When machines at the new plant and in nearby Brunswick are fully

running, 450 boot-making employees will beat back a near-constant

backlog. Twenty-seven-year-old Abdiweli Said is one of them. He

grew up in Dadaab and came to the US with older siblings. At LHS he

played varsity soccer. After that he went on to community college

and then to USM, where he studied international relations until the

costs and the commute got to him.

In the four years he’s worked at Bean, Abdiweli has absorbed the

lore. How back in 1912, L.L. got tired of wet feet while hunting

and designed himself some boots. Founded a company, mailed one

hundred pairs of boots to customers—satisfaction guaranteed—and got

ninety back. Nearly went out of business, but figured out just in

time why the bottoms were tearing from the uppers. Last year the

company produced 600,000 pairs of its iconic boot. Abdiweli owns a

pair. Actually, he owns two, but a friend appropriated the other

pair last winter.

One summer afternoon, Abdiweli works second shift. He and his

crewmates surround a device that forms polymer soles and bottoms.

Leather uppers get sewn on later. On the manufacturing floor: a

mechanical roar but surprisingly little smell. People fit socks

onto sized lasts, which disappear via conveyor into a molding

machine. Inside, polymer flows around the last. The resulting

piece—picture a rubber moccasin with no sole—is heat-fused with its

matching bottom into a waterproof half-boot. An aperture opens and,

in a maneuver that conjures a sportsman being ejected feetfirst,

the boots emerge soles-up on metal legs.

Robotic arms pluck the boots off the feet. Abdiweli trims excess

fabric. Someone applies the Bean label. Two others pack. Boom, a

dozen pairs of half-boots—done. Next stop, Brunswick.

Valentine calls a break. Workers gather for a photo for an upcoming

grand-opening celebration. The mayor has been invited, and the

governor. Bean executives will be here, too, to watch the crew run

the newest million-dollar molder. After the photo comes stretching:

backs, shoulders, arms, even fingers. Abdiweli leads a soccer

stretch—crosses legs, reaches hands toward feet, 1-2-3-4.

Two-thirds of Abdiweli’s crewmates come from Somalia or other parts

of Africa. The rest are white. “It’s a premier company,” he says.

“We work hard, but they take really good care of us”—by which he

means the breaks and the stretching, plus state-of-the-art

workspace, good pay, high-end health plan, employee fitness room,

and a designated space where he goes for salah.

The prayer space, and the fact that Bean gives Muslims paid holi

days on Eid-al-Fitr and Eid-al-Adha, means a lot. Abdiweli’s co-worker Safiya Khalid remembers a different experience at Kmart

where a supervisor admonished her for speaking Somali during a

break. “There was no understanding,” she says.

“Expect diversity,” people are told when they apply to Bean.

Valentine says he sees people and personalities, not ethnicity.

“When you work with someone day after day—skin color, head

coverings, all that sort of disappears.” Everyone is known for

something particular to their person—Abdiweli’s quick hands and

droll sense of humor; Safiya’s ability to multitask two stations at

once.

As immigrants in Lewiston have gained traction and established

lives, some have expanded their social networks to include longtime

residents who seem in need. Aba Abu, the Trinity Jubilee

caseworker, also drives a bus that picks up kids with special

needs. One of her passengers is a white boy who lives with his

father. The father, overwhelmed, often sends his son to school

wearing the same clothes as the day before. “It was sad to see him

like that in the morning,” Aba said. So she started buying shirts

to send home with the boy.

Acculturation has turned out to work both ways. Newcomers adapt

but also influence the broader community. At CMCC an instructor

reports that Somali eagerness for education is contagious. “When

[other students] see refugees taking their educational

opportunities seriously, it establishes a certain climate,” he

says. Last winter, on an afternoon when Nasafari was in class,

about a third of the students in the CMCC cafeteria were new

immigrants.

…

At the institutional level, advocates say racial equality is closer

than it was a decade ago—but not achieved. “Look, we’ve made

progress in Lewiston, but we’re not there yet,” says Fowsia Musse,

director of Maine Community Integration. Musse and others cite

improvements: organizations in which services are provided

horizontally rather than vertically—that is, new immigrants helping

each other rather than being “helped” by white administrators;

newcomers employed in city institutions as other than interpreters

and cultural brokers; a school system that while imperfect still

graduates most of its new-immigrant kids—and sends many on to

college.

*****************************************************************

Email Interview with Amy Bass and Cynthia Anderson

November 18-20, 2019

AfricaFocus: Both of you stress how Lewiston has welcomed Somali

and other African immigrants despite anti-immigrant sentiment by

many in the Lewiston community, further fueled by anti-immigrant

rhetoric and policy at the national level. How do you see this

playing out in Lewiston since you completed writing your books, and

what additional difficulties do you see for 2020, with an

approaching national election?

Amy Bass: Talking about Lewiston – or any community undergoing

rapid transformation – means it is constantly a story of steps

forward and steps back. There will be fractures, and there have

certainly been fractures since ONE GOAL came out, but there will

also be what I would call “coming togethers.” And I think that what

you have to hope for is that each fracture’s lasting damage will be

minimized, and the tools that have been assembled over the last

decade or so will be put to use quickly, making each coming

together moment more meaningful, stronger, and with a longer

lasting impact. I think the recent election of Safiya is a truly

bright moment in so many ways – to be the first person elected.

Everything she encountered in terms of hateful trolls was highly

unoriginal and expected, but it doesn’t make any of it easier to

stand. Yet she persisted and persevered and now will represent

Lewiston. But there are always stormy waters ahead – these things

are not new, but they are, perhaps, newly emboldened. And figuring

out paths forward will still require organization, community, and,

quite honestly, bravery.

Cynthia Anderson: I feel hopeful. HOME NOW ends in January 2019,

with the inauguration of a new Maine governor, progressive Janet

Mills. The prior governor had tried to withdraw the state from the

federal refugee resettlement program and held anti-immigrant views.

In choosing Mills, a Democrat and new-immigrant advocate, voters

spoke.

Refugees and asylees are a visible change not just in Lewiston but

in Maine overall. Integrating has been hard work—for the newcomers

and for the cities where they settled. It’s taken time and money

and concerted effort. It still does. One message of the 2018

midterm seemed to be that Mainers as a whole feel the effort is

worth it, that they believe they’re collectively becoming something

greater than they used to be.

AfricaFocus: You note that strong leaders in the school system and

city administration were key to crafting constructive policies.

Several Lewiston mayors with anti-immigrant views, for their part,

seem to have been catalytic in evoking a backlash of support for

immigrants. City council members, on the other hand, do not appear

prominently in either of your narratives. With this fall´s election

of Safiya Khalid to the council as well as a new mayor, do you

anticipate greater collaboration in a positive vein, or are there

likely to be new points of tension?

Amy Bass: See above – I guess I answered both.

Cynthia Anderson: Safiya Khalid brings new consciousness and a new

perspective to the city council, so I anticipate points of tension

and greater collaboration, both.

Safiya’s election is momentous. Media coverage focused on her

victory in spite of the trolls’ ugliness, but the real story is

that Ward 5—which is not majority new-immigrant— gave her 70

percent of their vote. To me this suggests evolving ease between

longtime Lewistonians and newcomers. This is the real news. Again

and again in writing HOME NOW I saw that the most vocal anti-Muslim

and anti-refugee voices in the state belonged to those who neither

live among nor know newcomers. Familiarity has yielded acceptance.

AfricaFocus: An AP story in

2017 stressed the contrast in views on immigrants between

Lewiston and the surrounding Androscoggin county, highlighting the

2016 national election results. National research studies also show

that anti-immigrant views are found disproportionately in

communities with less exposure to immigrants. In your opinion, are

efforts to counter these views, such as that by Catholic Charities

mentioned in the article, having any effect, either in Androscoggin

county or elsewhere in rural and small-town Maine? If not, what do

you think could be done differently? For example, are you aware of

political leaders or non-profit groups trying to address the issues

of rural Mainers both feeling and actually being left behind?

Amy Bass: Not really a question that is in my current

wheelhouse -- super specific to local politics, and there are

plenty of people

on the ground in Lewiston who should it far before I should. I will

say this, however: ONE GOAL isn’t just about soccer. It’s about

points of contact – very deliberate points of contact. One of the

biggest battles Lewiston soccer confronts, whether it is facing a

midcoast team or a rural team, is the world view of the other team,

the coaches, and the officials. That is contact. That is saying

“Here we are” within the specific rules of a game, a game that

emphasizes continuity over fracture, a game that asks both sides to

move a ball largely (although not entire) without a whole lot of

contact. That’s important. So for me, it isn’t about the political

leaders or groups – it’s politics by other means, and in this case,

those means are soccer. And it’s doing some of the hard work,

creating teammates on clubs like Seacoast United, and forging bonds

that go beyond that of opponent.

Cynthia Anderson: Safiya Khalid was elected because she’s smart and

hard-working—voters saw this AND they’d reached a point where they

no longer feared her as a Somali Muslim refugee— as “other.”

Contact and shared experience did that. The point is that the views

of people in other Androscoggin County towns already are

changing—and will keep changing—as new immigrants move into those

communities and/or people continue to get to know each other at

work and at school, etc. When I met Safiya Khalid a couple of years

ago, she had a job at L.L. Bean on a boot-making crew composed half

of longtime Mainers and half of new immigrants. As the crew manager

put it: “When you work with someone day after day—skin color, head

coverings, all that sort of disappears.”

As for rural Mainers feeling (and being) left behind, this is

something I know keenly, having grown up in the western part of the

state. The closures of mills and factories meant the loss of well-

paying jobs, of course, but also a wholesale loss of morale over a

generation. And that loss bred longing for the past and resentment

of the new (including refugees and the resources they might

consume). Western Maine’s biggest challenge is the creation of more

living-wage jobs—for longtime residents and newcomers alike.

AfricaFocus: Although every community experience is unique, it

seems that there might be many similarities as well as contrasts

between the experiences with African immigrants of Lewiston and

Portland in particular. Do you have any reflections on this? Is

there any organized dialogue on this between communities or

officials in the the two cities?

Amy Bass: There’s tons of dialogue, and has been from day one, when

Portland shifted those first families to Lewiston, and created the

collaborative. But again, rather than look at organized anything,

look at the networks that people forge themselves, whether it is

with a group like MEIRS or one like Gateway. Understanding that

these things work outside of, and often in spite of, what might be

considered traditional frameworks of politics, is critical in

understanding what has worked, and what hasn’t.

Cynthia Anderson: Amy’s right that much of the

dialogue/collaboration between Lewiston and Portland is informal

rather than structured or official. This is partly because with

time refugees increasingly have taken over responsibility for their

own adjustment to life in the U.S. Newcomers run nonprofits and

other agencies; they prioritize goals and advocate for themselves.

In HOME NOW, I talk about the strong web of outreach from new

immigrants to newer immigrants. Self-sufficiency means having the

ability to handle issues within the community—and to talk and work

inter-agency, informally, as well as with city officials.

***************************************************************

Additional Sources

On African immigrants in the United States

Background and statistics from the Migration Policy Institute,

November 6, 2019. Sub-Saharan African Immigrants in the

United States.

An interactive view of the map above is available from Migration Policy Institute at

https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/us-immigrant-population-metropolitan-area

Book forthcoming in December 2019: Voices of African Immigrants in Kentucky: Migration, Identity, and

Transnationality (Kentucky Remembered: An Oral History Series)

by Francis Musoni, Iddah Otieno, Angene Wilson, Jack Wilson.

On the economic need for immigration

Charles Kenny, “The Real Immigration Crisis: The Problem Is Not Too

Many, but Too Few”

Foreign Affairs, November 11, 2019

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2019-11-11/real-immigration-crisis

Background on Maine current economy and politics

Bangor Daily News, November 2016

http://mainefocus.bangordailynews.com/2016/11/down-the-road/#.XdA6xHVKjTc

Maine Center for Economic Policy, July 2017

https://www.mecep.org/a-new-great-depression-in-rural-maine/

The Nation, October 2018

https://www.thenation.com/article/what-a-rural-maine-house-race-can-teach-the-left/

Maine Center for Economic Policy, November 2018

https://www.mecep.org/state-of-working-maine-2018-examines-job-quality-offers-solutions-to-make-good-jobs-the-norm/

More on African refugees and other migrants in Lewiston and Maine

April 2017

https://apnews.com/7f2b534b80674596875980b9b6e701c9/How-a-community-changed-by-refugees-came-to-embrace-Trump

March 2019

https://bangordailynews.com/2019/03/13/news/lewiston-auburn/mayors-racist-texts-cause-pain-in-maine-home-to-refugees/

June 2019

https://www.pri.org/stories/2019-06-17/portland-maine-turns-crisis-opportunity-african-migrants

https://www.npr.org/2019/06/19/734165446/the-recent-influx-of-african-asylum-seekers-is-taxing-social-services-in-maine

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/23/us/portland-maine-african-migrants.html

August 2019

https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Society/2019/0813/Among-those-helping-Maine-s-new-arrivals-Other-immigrants

And a few articles of interest about Somali Americans in Minnesota

(among many recent news articles; see customized Google news search)

Ilhan Omar´s constituents push back against Trump taunts (including

3-minute video), October 2019

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/us-politics/trump-ilhan-omar-minneapolis-rally-somalis-racist-2020-election-latest-a9170536.html

Why Minnesota question answered by Star Tribune, June 2019

http://www.startribune.com/how-did-the-twin-cities-become-a-hub-for-somali-immigrants/510139341/

Why Minnesota question answered by local TV, July 2019

https://minnesota.cbslocal.com/2019/07/23/minnesota-somali-american-population-good-question/

American football, too, Willmar, Minnesota, November 2018

https://theundefeated.com/features/football-hero-hamza-mohamed-for-a-new-generation-of-somali-americans/

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication

providing reposted commentary and analysis on African issues, with

a particular focus on U.S. and international policies. AfricaFocus

Bulletin is edited by William Minter.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please

write to this address to suggest material for inclusion. For more

information about reposted material, please contact directly the

original source mentioned. For a full archive and other resources,

see http://www.africafocus.org

|