|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

South Africa: Xenophobia, Deep Roots, Today´s Crisis

AfricaFocus Bulletin

September 12, 2019 (2019-09-12)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

“In the early years after I got 'home,' it took me some time to

figure out how to respond to the idea that Africa was a place that

began beyond South Africa's borders. I was surprised to learn that

the countries where I had lived -- the ones that had nurtured my

soul in the long years of exile -- were actually no places at all

in the minds of some of my compatriots. … Though they thought

themselves to be very different, it seemed to me that whites and

blacks in South Africa were disappointingly similar when it came to

their views on 'Africa.' … This warped idea of Africa was at the

heart of the idea of South Africa itself. Just as whiteness means

nothing until it is contrasted with blackness as savagery, South

African-ness relies heavily on the construction of Africa as a

place of dysfunction, chaos and violence in order to define itself

as functional, orderly, efficient and civilised.” - Sisonke Msimang

As Daniel Magaziner wrote in South Africa´s Business Day on September 9, the

current xenophobic violence in South Africa is hardly unique to

that country, citing the similar violent rhetoric and actions that

have marked the United States as well. Increasing inequality paired

with the willingness of politicians to incite or tacitly tolerate

hate speech and hate crimes are indeed features in many countries

around the world. Magaziner notes that “In the wake of such horror

it is not surprising to see politicians and regular people cry,

rend their garments and insist that ´this is not who we are.´ But I

am not sure. I think maybe it is.”

In both the United States and South Africa, as arguably in many

other countries, confronting anti-immigrant mobilization requires

not only appeals to unity but also confronting deeply embedded

assumptions about national history and national identity.

While this AfricaFocus Bulletin contains links (at the end), to

current news and analysis of the latest violence, I decided to

prioritize reprinting the 2014 essay by Sisonke Msimang, originally

published by

http://africasacountry.com, for its eloquent posing of

questions still unanswered. Also included are one article and

additional links featuring recent public opinion surveys by South

Africa´s Human Sciences Research Council.

Another AfricaFocus Bulletin sent out today and available at

http://www.africafocus.org/docs19/sa1909b.php contains the

full text of the speech by South African President Cyril Ramaphosa

on xenophobia and gender-based violence, as well as several other

related links.

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on South Africa, visit

http://www.africafocus.org/country/southafrica.php.

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on migration, visit

http://www.africafocus.org/migrexp.php.

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

Belonging--why South Africans refuse to let Africa in

Sisonke Msimang

October 22, 2014

https://africasacountry.com/2014/04/belonging-why-south-africans-

refuse-to-let-africa

[Sisonke Msimang writes about money, power and sex. She lives in

Johannesburg.]

Any African who has ever tried to visit South Africa will know that

the country is not an easy entry destination. South African

embassies across the continent are almost as difficult to access as

those of the UK and the United States. They are characterised by

long queues, inordinate amounts of paperwork, and officials who

manage to be simultaneously rude and lethargic. It should come as

no surprise then that South Africa's new Minister of Home Affairs

has announced the proposed establishment of a Border Management

Agency for the country. In his words the new agency "will be

central to securing all land, air and maritime ports of entry and

support the efforts of the South African National Defence force to

address the threats posed to, and the porousness of, our

borderline."

Political observers of South Africa will understand that this is

bureaucratic speak to dress up the fact that insularity will

continue to be the country's guiding ethos in its social, cultural

and political dealings with the rest of the continent.

Perhaps I am particularly attuned to this because of my upbringing.

I am South African but grew up in exile. That is to say I was

raised in the Africa that is not South Africa; that place of

fantasy and nightmare that exists beyond the Limpopo. When I first

came home in the mid 1990s, in those early months as I was learning

to adjust to life in South Africa, I was often struck by the odd

way in which the term 'Africa,' was deployed by both white and

black South Africans.

Because I speak in the fancy curly tones of someone who has been

educated overseas, I was often asked where I was from. I would

explain that I was born to South African parents outside the

country and that I had lived in Zambia and Kenya and Canada and

that my family also lived in Ethiopia. Invariably, the listener

would nod sympathetically until the meaning of what I was saying

sank in. 'Oh.' Then there would be a sharp intake of breath and a

sort of horrified fascination would take hold. "So you grew up in

Africa." The Africa was enunciated carefully, the last syllable

drawn out and slightly raised as though the statement were actually

a question. Then the inevitable, softly sighed, "Shame."

In the early years after I got 'home,' it took me some time to

figure out how to respond to the idea that Africa was a place that

began beyond South Africa's borders. I was surprised to learn that

the countries where I had lived -- the ones that had nurtured my

soul in the long years of exile -- were actually no places at all

in the minds of some of my compatriots. They weren't geographies

with their own histories and cultures and complexities. They were

dark landscapes, Conradian and densely forested. Zambia and Kenya

and Ethiopia might as well have been Venus and Mars and Jupiter.

They were undefined and undefined-able. They were snake-filled

thickets; impenetrable brush and war and famine and ever-present

tribal danger.

Though they thought themselves to be very different, it seemed to

me that whites and blacks in South Africa were disappointingly

similar when it came to their views on 'Africa.' At first I blamed

the most obvious culprit: apartheid. The ideology of the National

Party was profoundly insular, based on inspiring everyone in the

country to be fearful of the other. With the naiveté and arrogance

of the young, I thought that a few lessons in African history might

help to disabuse the Rainbow Nation of the notion that our country

was apart from Africa. I made it my mission to inform everyone I

came across that culturally, politically and historically we could

call ourselves nothing if not Africans.

What I did not fully understand at that stage was that it would

take more than a few lectures by an earnest 'returnee,' to deal

with this issue. This warped idea of Africa was at the heart of the

idea of South Africa itself. Just as whiteness means nothing until

it is contrasted with blackness as savagery, South African-ness

relies heavily on the construction of Africa as a place of

dysfunction, chaos and violence in order to define itself as

functional, orderly, efficient and civilised.

As such, the apartheid state was at pains to keep its borders

closed. The savages at the country's doorstep were a convenient

bogeyman. Whites were told that if the country's black neighbours

were let in, they would surely unite with the indigenous population

and slit the throats of whites. By the same token, black people

were told that the Africans beyond South Africa's borders lived

like animals; they were ruled by despots and governed by black

magic.

When apartheid ended, the fear of African voodoo throat slitting

should have ended with it. Indeed on the face of things, the fear

of 'Africa,' has abated and has been replaced by the language of

investment. South African capital has 'opened up' to the rest of

the continent and so fear has been taken over by self-interest and

new forms of extraction.

In the parlance of South Africans, our businesses have 'gone into

Africa.' Like the frontiersmen who conquered the bush before them

they have been quick to talk about 'investment and opportunity' to

define our country's relationship with the continent. The pre-1994

hostility towards 'Africa' has been replaced by a paternalism that

is equally disconcerting. Africa needs economic saviours and white

South African 'technical skills' are just the prescription.

Amongst many black South Africans, the script is frightfully

similar. The recent collapse of TB Joshua's church in Nigeria, in

which scores of South Africans lost their lives, has highlighted

how little the narrative has changed in the minds of many South

Africans. Many have called in to radio shows and social media

asking, what the pilgrims were doing looking for God in such a God

forsaken place?

In the democratic era we have converted the hatred of Africa into a

crude sort of exceptionalist chauvinism. South Africans are quick

to assert that they don't dislike 'Africans.' It's just that we are

unique. Our history and society are too different from theirs to

allow for meaningful comparisons. See -- we are even lighter in

complexion than them and we have different features. I have heard

the refrain too many times, 'We don't really look like Africans.'

Never mind the reality that black South Africans come in all shades

from the deepest of browns to the fairest of yellows.

This idea that South Africans are so singular in our experience;

that apartheid was such a unique experience that it makes us

different from everyone else in the world, and especially from

other Africans, is an important aspect of understanding the South

African approach to immigration.

As long-time researcher Nahla Vahlji has noted, "the fostering of

nationalism produces an equal and parallel phenomenon: that of an

affiliation amongst citizens in contrast and opposition to what is

'outside' that national identity." In other words, South Africans

may not always like each other across so-called racial lines, but

they have a kinship that is based on their connection to the

apartheid project. Outsiders -- those who didn't go through the

torture of the regime -- are juxtaposed against insiders. In other

words foreigners are foreign precisely because they can not

understand the pain of apartheid, because most South Africans now

claim to have been victims of the system. Whether white or black,

the trauma of living through apartheid is seen as such a defining

experience that it becomes exclusionary; it has made a nation of

us.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) which sought to

uncover the truth behind certain atrocities that took place under

apartheid, was also an attempt to make a nation out of us. While it

won international acclaim as a model for settling disputes that was

as concerned with traditional notions of justice as it was with

healing the wounds of the past, there were many people inside South

Africa who were sceptical of its mission. As Premesh Lalu and

Brendan Harris suggested as the Commission was starting its work in

the mid 1990s, the desire for the TRC to create the narrative of a

new nation led to a selection of "elements of the past which create

no controversy, which create a good start, for a new nation where

race and economic inequality are a serious problem, and where the

balance of social forces is still extremely fragile."

This is as true today as it was then. Attending the hearings was

crucial for me as a young person yearning to better understand my

country, but I am objective enough to understand that one of the

consequences using the TRC as the basis for forging a national

identity is that 'others' -- the people who were not here in the

bad old days -- have found it difficult to find their place in

South Africa. Aided and abetted by the TRC and the discursive

rainbow nation project, South Africans have failed to create a

frame for belonging that transcends the experience of apartheid.

Twenty years into the 'new' dispensation, many South Africans still

view people who weren't there and therefore who did not physically

share in the pain of apartheid as 'aliens.' The darker-hued these

aliens are, the less likely South Africans are to accept them. Even

when black African 'foreigners' attain citizenship or permanent

residence, even when their children are enrolled in South African

schools, they remain strangers to us because they weren't caught up

in our grand narrative as belligerents in the war that was

apartheid.

While it is easy to locate the roots of xenophobia in our colonial

and apartheid history, it is also becoming clear that our present

leaders do not understand how to press the reset button in order to

remake our country in the image of its future self. They have not

been able to outline a vision for the new South Africa that is

inclusive of the millions of African people who live here and who

are 'foreign' but indispensable to our society for cultural,

economic and political reasons.

America -- with all its problems -- offers us the model of an

immigrant nation whose very conception relied on the idea of the

'new' world where justice and freedom were possible. Much can be

said about how that narrative ignores those who were brought to the

country as slave cargo. It is patently clear that America has also

denied the founding acts of genocide that decimated the people of

the First Nations who lived there before the settlers arrived.

Indeed, one could argue that while oppression and murder begat the

United States of America, the country's founding myth is an

inclusive one, a story of freedom and the right to life. In South

Africa murder and oppression also birthed a new nation, but the

founding myth of our post 1994 country has remained insular and

exclusive, a story of freedom and the right to life for South

Africans.

The South African state has always been strongly invested in seeing

itself as an island of morality and order in a cesspool of black

filth. The notion of South Africa's apartness from Africa is deeply

embedded in the psyche that 'new' South Africans inherited in 1994

but it goes back decades. For example, the 1937 Aliens Act sought

to attract desirable immigrants, whom it defined in the law as

those of 'European' heritage who would be easily assimilable in the

white population of the country.' This law stayed on the books

until 1991, when the National Party, in its dying days, sought to

protect itself from the foreseeable 'deluge' of communist and/or

barbaric Africans. The Aliens Control Act (1991) removed the

offensive reference to 'Europeans' but it kept the rest of the

architecture of exclusion intact.

March against xenophobia, Newtown, South Africa, 2015. Photo credit: GCIS.

As a result, when the new South Africa was born the old state

remained firmly in place, continuing to guard the border from the

threats just across the Limpopo, as it always had. It was a decade

before the Bill on International Migration came into force in 2003

and it too retained critical elements of the old outlook.

The ANC politicians running the country somehow began to buy into

the idea that immigrants posed a threat to security. Immigration

continued to be seen as a containment strategy rather than as a

path to economic growth. As President Jacob Zuma tightens his grip

on the security sector, and extends the power and reach of the

security cluster in all areas of governance, this attitude seems to

be hardening rather than softening.

None of South Africa's current crop of political leaders seem to be

asking the kinds of questions that will begin to resolve the

question the role that immigration can and should play in the

building of our new nation. South Africa's political leadership

sees Africa in one of two ways: either as a market for South

African goods, differentiated only to the extent that Africans can

be sold our products; or as a threat, part of a deluge of the poor

and unwashed who take 'our jobs and our women.'

No one in government today seems to understand that postapartheid

South Africa continues to be the site of multiple African

imaginations. One cannot deal with 'Africa' without dealing with

the subjectivity of what South Africa meant to Africa historically,

and the disappointment that a free South Africa has signified in

the last decade.

So much of the pan-Africanist project -- even with its failings --

has been about an imagined Africa in which the shackles of

colonialism have been thrown off. South Africa has always been an

iconic symbol in that imaginary. Robben Island and Nelson Mandela,

the burning streets of Soweto, Steve Biko's bloodied, broken body:

these images did not just belong to us alone. They brought pain and

grief to a continent whose march towards self-determination

included us, even when our liberation seemed far, far away. With

the invention of the 'new' South Africa the crucial importance of

African visions for us have taken a back seat. South Africans have

refused to admit that we are a crucial aspect of the African

project of self-determination. In failing to see ourselves in this

manner, we have denied ourselves the opportunity to be propelled --

transported even -- by the dreams of our continent.

What would South Africa be like without the 'foreign' academics who

teach mathematics and history on our campuses? How differently

might our students think without their deep and critical insights

about us and the place we occupy in the world? How might we

understand our location and our political geography differently if

'foreigners' were not here offering us different ways of wearing

and inhabiting blackness? What would our society look like without

the tax paying 'foreigners' whose children make our schools richer

and more diverse? What would inner city Johannesburg smell like

without coffee ceremonies and egusi soup? What would Cape Town's

Greenmarket square be without the Zimbabwean and Congolese taxi

drivers who literally make the city go?

In an era in which borders are coming down and becoming more porous

to encourage trade and contact, South Africa is introducing layers

of red tape to the process of moving in and out of the country. The

outsider has never been more repulsive or threatening than s/he is

now. This is precisely why Gigaba's announcement of the Border

Management Agency is so worrisome. Yet it was couched in careful

language. Ever mindful of the xenophobic reputation that South

Africa has in the rest of the continent, Gigaba asserts, "We value

the contributions of fellow Africans from across the continent

living in South Africa and that is why we have continued to support

the AU and SADC initiatives to free human movement; but [my

emphasis] this cannot happen haphazardly, unilaterally or to the

exclusion of security concerns."

Ah, there it is! The image of Africa and 'Africans' as haphazard,

disorderly and ultimately threatening is in stark contrast to South

Africa and South Africans as organised, efficient and (ahem) peace-

loving. The subtext of Gigaba's statement is that South Africans

require protection from 'foreigners' who are hell bent on imposing

their chaos and violence on us.

Nowhere has post-apartheid policy suffered from the lack of

imagination more acutely than in the area of immigration. Before

they took power, many in the ANC worried about the ways in which

the old agendas of the apartheid regime state would assert

themselves even under a black government. They understood that

there was a real danger of the apartheid mentality capturing the

new bureaucrats. Despite these initial fears, the new leaders

completely under-estimated the extent to which running the state

would succeed in dulling the imaginations of the new public

servants and burying their intellect under mountains of forms and

rules and processes. They also didn't understand that xenophobia

would be so firmly lodged in the soul of the country, that it would

be one of the few phenomena would unite blacks and whites.

South Africa's massive immigration fail is a tragedy for all kinds

of reasons. At the most basic level, the horrific levels of

violence and intimidation that many African migrants to South

Africa face on a daily basis represent an on-going travesty of

justice. Yet in a far more complex and nuanced way, South Africa's

rejection of its African identity is a tragedy of another sort. All

great societies are melanges, a delicious brew of art and culture

and intellect. They draw the best from near and far and make them

their own. By denying the contribution of Africa to its DNA, South

Africa forgoes the opportunity to be a richer, smarter, more

cosmopolitan and interesting society than it currently is.

In spite of ourselves South Africans still have a chance to open

our arms to the rest of the continent. The window of opportunity

for allowing our guests to truly belong to us as they have always

allowed us to belong to them is still open. I fear however, that

the window is closing fast.

*******************************************************************

Why do people attack foreigners living in South Africa?: Asking

ordinary South Africans

Steven Gordon

HSRC Review, September 2018.

http://www.hsrc.ac.za/en/review/hsrc-review-sept-2018/foreigners-in-sa

A new study from the Human Sciences Research Council contributes to

our public debate on anti-immigrant violence by looking at the

opinions of ordinary South Africans. Using public opinion data, Dr

Steven Gordon looks at which explanations for anti-immigrant

violence are most popular amongst the country’s adult population.

By understanding how the public views this important question, we

can better comprehend which xenophobia prevention mechanisms would

be most acceptable to the general population.

The South African Constitution is regarded as one of the most

progressive in the world. One of its central features is the

recognition of the right of all citizens to certain socio-economic

rights including basic housing, healthcare, education, food, water,

and social security. Including socio-economic rights in the

Constitution has direct, practical implications for government,

which is expected to fulfil these rights through concrete action.

It is crucial that government’s progress in delivering on these

expectations is monitored.

The HSRC’s South African Social Attitude Survey (SASAS) series is a

useful tool to measure the extent to which South Africans are

satisfied with their socio-economic circumstances, but the series

does not measure the extent to which government has complied with

its obligation to progressively realise socio-economic rights. Such

a measurement would require insight into the national budget and

what portion of the budget the state dedicates to socio-economic

goods. However, how South Africans perceive their circumstances

matter and it provides valuable insight into how government has

fared in providing basic goods such as water, sanitation, housing

and electricity.

Anti-immigrant violence is one of the major problems facing South

Africa. This type of hate crime discourages long-term integration

of international migrants and acts as a barrier to otherwise

economically beneficial population movement. It also sours the

country’s international relationships on the African continent.

Relations between South Africa and Nigeria (one of the region’s

largest economies) have, for example, deteriorated because of

recent episodes of anti-immigrant attacks. Since the early 1990s,

state officials, legislators and policymakers in South Africa have

debated the causes of anti-immigrant violence. There are a thousand

different opinions on what causes such hostility and some

politicians (like former President Jacob Zuma) have even suggested

that this problem does not exist.

Getting an unbiased survey answer

Data from the South African Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS) 2017

was used for this study. A repeated cross-sectional survey series,

SASAS is specially designed to be nationally representative of all

persons 16 years and older in the country. Survey teams visited

households in all nine provinces and the sample size was 3,098.

Fieldworkers informed respondents that they were going to be asked:

“some questions about people from other countries coming to live in

South Africa”. Respondents were then asked the following: “There

are many opinions about why people take violent action against

foreigners living in South Africa. Please tell me the MAIN REASON

why you think this happens.” This question was open-ended which

allowed respondents to answer in their own words. This encouraged

respondents to give an unbiased answer.

The response

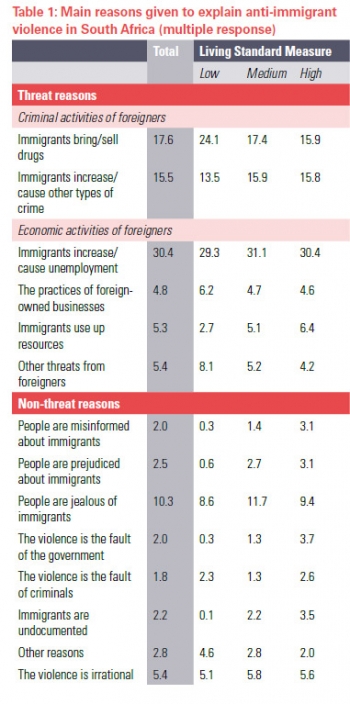

Using SASAS, I identified main causes of xenophobic violence given

by the public. These explanations are depicted in Table 1 across

economic groups. Here, I use the well-known Living Standard

Measure: Low (1-4), Medium (5-6) and High (7-10). Almost every

person interviewed was able to offer an explanation for why people

attack foreigners in South Africa. Only a small minority (5%)

described such violence as irrational, illogical or unknowable. An

even smaller portion (2%) of the public rejected the premise of the

question and said that attacks against foreigners were ‘just the

work of criminals’. Before the different reasons are discussed in

more detail, it is important to note that when talking about

international migrants, respondents made little distinction between

different types of foreigners. Most made general reference to this

group and only a relatively small proportion cited specific types

(e.g. undocumented) of foreigners.

The financial explanation

The most popular explanation given for attacks against

international migrants concerned the negative financial effect that

immigrants had on South African society. About a third (30%) of the

public identified the labour market threat posed by foreigners as

the main reason for anti-immigrant violence. The other main

economic causes identified by the general public were: (i) the

unfair business practices of foreign-owned shops and small

businesses; and (ii) immigrants use up resources (such as housing).

It is interesting to note that poor people were not more likely to

give economic reasons than the wealthy.

Criminal activity

The criminal threat posed by international immigrants was the

second most frequently mentioned cause of anti-immigrant violence.

Almost a third (30%) of the adult population said that the violence

occurred because communities were responding to the criminal

activities of international migrants. Many people attributed the

violence to foreigners’ involvement in illegal drug trafficking

specifically. Poor people were found to be particularly likely to

give illicit drug trading by foreigners as a main cause. About 5%

of adults identified other threats from foreigners as the main

reason for the attacks. These threats included disease, sexual

exploitation of women and children as well as a general sense that

immigrants wanted to ‘take over the country’.

Jealousy

Overall, 70% of the general public identified the threat posed by

immigrants as the main explanation for anti-immigrant violence in

South Africa. Looking at the minority that named a non-threat

explanation for the violence, we found that few identified

individual prejudice or misinformation spread about international

migrants as a reason for anti-immigrant violence. Remarkably, the

most frequent non-threat explanation for violence was jealousy.

Approximately 10% of the population told fieldworkers that envy of

the success or ingenuity of foreigners had caused this kind of hate

crime. People who responded in this way tended to tell fieldworkers

that South Africans were lazy when compared to international

migrants.

Conclusion

Most South Africans have a strong opinion about why anti-immigrant

violence occurs in the country. Reviewing the responses given to

fieldworkers, it is apparent that the majority of reasons provided

by the general population concern the harmful conduct of

international migrants. There is no evidence to support the belief

that South Africa’s international migrant community is, however, a

significant cause of crime or unemployment in the country. Indeed,

as former President Jacob Zuma has himself acknowledged, many in

the migrant community “contribute to the economy of the country

positively”. Current Minister of Home Affairs Malusi Gigaba has

himself said that it is wrong to claim that all foreigners are drug

dealers or human traffickers.

If a progressive solution to anti-immigrant violence is to be

found, then there is a need to persuade the general population to

support a different interpretation of the causes of anti-immigrant

violence. Only with public support can anti-xenophobia advocates

end hate crime against immigrants in South Africa. Government and

activists need to change the way ordinary people think about this

type of hate crime.

Additional articles based on HSRC survey

“How should xenophobic hate crime be addressed? Asking ordinary

people for solutions”

HSRC, 6 August 2019

http://www.hsrc.ac.za/en/media-briefs/sasas/how-should-xenophobic-

hate-crime

Steven Gordon, “What research reveals about drivers of anti-

immigrant hate crime in South Africa”

The

Conversation, September 6, 2019

**********************************************************

Additional Sources

News stories on the xenophobic attacks in South Africa have been

plentiful. For coverage by Google news worldwide visit http://tinyurl.com/y2yw5j37.

Coverage on South Africa news sites can be found at http://tinyurl.com/y4h5w4v8, and

coverage on Nigerian websites at http://tinyurl.com/y5ll7nae.

For a series of stories that go beyond the news to sharp analysis

and first-hand coverage, the South African site New Frame stands

out:

https://www.newframe.com/?s=xenophobia.

Commentaries in The

Daily Maverick can be found at http://tinyurl.com/y5dlqlkr.

On the relationship of South Africa to other African countries,

three commentaries that are particularly worth reading are:

Nnimmo Bassey, “Xenophobia and the New Apartheid,” September 4,

2019

https://nnimmobassey.net/2019/09/04/xenophobia-and-the-new-

apartheid/

Tafi Mhaka & Suraya Dadoo, “South Africa is becoming a pariah in

Africa,” September 10, 2019

https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/south-africa-pariah-

africa-190909145153827.html

Nanjala Nyabola, “Failed decolonisation of South African cities

fuels violence,” September 11, 2019

https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/failed-decolonisation-

south-african-cities-leads-violence-190910123546431.html

For an in-depth analyses of South African public opinion on

xenophobia, see the 2013 and 2014 monographs from the Southern African

Migration Project (SAMP): Migration Policy Series 63 and 66,

under the titles Soft Targets and Xenophobic Violence

in South Africa.

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication

providing reposted commentary and analysis on African issues, with

a particular focus on U.S. and international policies. AfricaFocus

Bulletin is edited by William Minter.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please

write to this address to suggest material for inclusion. For more

information about reposted material, please contact directly the

original source mentioned. For a full archive and other resources,

see http://www.africafocus.org

|