|

Algeria

Angola

Benin

Botswana

Burkina Faso

Burundi

Cameroon

Cape Verde

Central Afr. Rep.

Chad

Comoros

Congo (Brazzaville)

Congo (Kinshasa)

Côte d'Ivoire

Djibouti

Egypt

Equatorial Guinea

Eritrea

Ethiopia

Gabon

Gambia

Ghana

Guinea

Guinea-Bissau

Kenya

Lesotho

Liberia

Libya

Madagascar

Malawi

Mali

Mauritania

Mauritius

Morocco

Mozambique

Namibia

Niger

Nigeria

Rwanda

São Tomé

Senegal

Seychelles

Sierra Leone

Somalia

South Africa

South Sudan

Sudan

Swaziland

Tanzania

Togo

Tunisia

Uganda

Western Sahara

Zambia

Zimbabwe

|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

USA/Africa: China, Bolton, and Jimmy Carter

AfricaFocus Bulletin

January 30, 2019 (190130)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

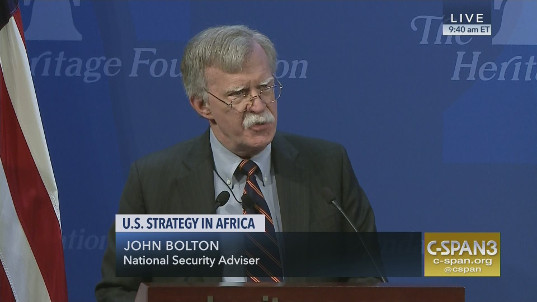

When National Security Advisor John Bolton presented

the administration´s "New Africa Strategy" at the

conservative Heritage Foundation on December 13, the

Washington Post headlined Bolton´s warning that

“´predatory´ China is outpacing the U.S.

In Africa" (http://tinyurl.com/ydgrr7ep). And, according to the

New York Times, "Bolton Outlines a Strategy for

Africa That’s Really About Countering China"

(http://tinyurl.com/yc73fx9j). But however prominent

the theme of U.S.-China competition in current news,

neither this framework nor any other overarching

theme is likely to prove a reliable guide as either a

description or prescription for actual policy.

In fact, the Trump administration´s Africa policy

will likely continue to be as chaotic as

administration policy more generally, and more of a

continuity with the policy of previous administrations than it appears from the rhetoric

from senior officials. However extreme the

incoherence now, the failure of a single framework to

define policy, as both historians and analysts of

current events can attest, is not an exception but

rather commonplace. Outcomes for specific issues and

countries result from a complex interaction of

causes, including those unrelated to priorities set

from the top.

This AfricaFocus Bulletin contains excerpts from and

links to relevant recent articles illustrating this

point in relation to the US-China rivalry. More

broadly, on economic issues, the joint economic

policy prescriptions advanced not only by the United

States but also by multilateral institutions such as

the European Union, World Bank, and International

Monetary Fund are at least as important as the

bilateral U.S.-China competition. And in confronting

African security crises, country-specific and regionspecific

factors appear to continue to be more

important than the China rivalry in U.S. responses to

cases including the Democratic Republic of the Congo,

Zimbabwe, Nigeria, Western Sahara, Somalia, and the

Sahel.

It is far beyond the scope of one Bulletin to delve

into U.S. security policy in these highly diverse

contexts, in which policies of African and European

governments, advocacy by human rights and

humanitarian organizations, the United Nations, and

disagreements within the U.S. Government all play a

role. But one useful general guide is to acknowledge

that policy is shaped both by general paradigms as

well as particular circumstances. In the security

realm, despite Bolton, US-China competition is still

far lower in impact on actual policy than the

overarching themes of counter-terrorism and

international response to instability.

Another AfricaFocus Bulletin sent out today, and

available on the web at http://www.africafocus.org/docs19/usa1901b.php,

features excerpts from Elizabeth Schmidt´s recently

published book on Foreign Intervention in Africa

after the Cold War, containing both overarching

frameworks for analysis and a carefully selected set

of case studies.

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on the USA and

Africa, visit http://www.africafocus.org/country/usa-africa.php

For the text of Ambassador Bolton´s speech and other

relevant articles, see

https://allafrica.com/view/group/main/main/id/00065416.html

Remarks by National Security Advisor Ambassador John

R. Bolton on the Trump Administration's New Africa

Strategy, Heritage Foundation, Dec. 13,2018

https://allafrica.com/stories/201812140155.html

State Department, Fact Sheet - President Donald J.

Trump's Africa Strategy Advances Prosperity,

Security, and Stability

https://allafrica.com/stories/201812140153.html

Testimony, Tibor P. Nagy, Jr., Assistant Secretary,

Bureau of African Affairs, House Foreign Affairs

Committee, Washington, DC, December 12, 2018

https://allafrica.com/stories/201812130046.html

For an emphasis not so much on China but on U.S.-

Africa business opportunities, see Anthony Carroll,

"Some Thoughts on President Trump’s Strategy for

Africa," Council on Foreign Relations, Dec. 18, 2018

http://tinyurl.com/yaf58lfn

Contrasting views on China

While Bolton stressed the threat from China, both the

talking points and congressional testimony from the

State Department featured more anodyne and familiar

tropes about “prosperity, security, and stability.”

Assistant Secretary of State Nagy included only one

sentence referring to China: "The Administration will

encourage African leaders to choose sustainable

foreign investments that help states become selfreliant,

unlike those offered by China that impose

undue costs."

And commentators excerpted below took radically

different views on whether the relationship with

China was or should be so polarized. Arthur Herman in

the National Review presented an even more alarmist

take than Bolton himself. But Jimmy Carter in an oped

in the Washington Post stressed that “Africans —

like billions of other people around the world — do

not want to be forced to choose a side.”

John Stremlau, a former official of the Carter Center

and now a professor at the University of the

Witwatersrand, argued at length that “Trump’s Africa

strategy should have cast China as a regional

partner, not a global adversary,”

Two recent articles also point to the complexity of

U.S.-China relations in Africa.

Edward Wong, "Competing Against Chinese Loans, U.S.

Companies Face Long Odds," New York Times, Jan. 13,

2019

http://tinyurl.com/y9bolzrj

Detailed account of how a U.S. company won over

Chinese competitors in a deal for an oil refinery in

Uganda. A reminder that both the U.S. and China,

despite their commitments to renewable energy, are

also investing in the fossil fuel sector in which

short-term benefits for Africa will be quickly

outweighed by long-term damage to the environment and

climate.

Aaron Mehta, “How the US and China collaborated to

get nuclear material out of Nigeria — and away from

terrorist group,“ Defensenews.com, Jan. 14, 2019

http://tinyurl.com/ybcqy3ln

Detailed account of how the US, China, and Russia as

well worked with Nigeria to transfer vulnerable

highly enriched uranium (now not needed for civilian

research use) away from a research reactor in Kaduna

back to China for safekeeping.

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

The Coming Scramble for Africa

By Arthur L. Herman

National Review, December 26, 2018

http://tinyurl.com/yabaz2lp

China, and Russia to a degree, are ahead of the game,

but the U.S. has the advantage going forward.

In the 19th century, Europe’s great powers were

caught up in what historians have dubbed “the

scramble for Africa,” as Britain, France, Germany,

and Italy competed with one other to establish

colonies and control over the so-called Dark

Continent — a competition that increased

international tensions and ultimately helped to set

the stage for the First World War.

Today a new scramble is underway, pitting the United

States and China and, to a lesser degree, Russia

against one other as they try to coax into their

respective camps the new Africa that’s emerging in

the 21st century.

At stake are Africa’s rich natural resources, rapidly

growing markets, and political and military influence

over the planet’s Southern Hemisphere — and a major

portion of the world’s population. This scramble will

do much to shape the 21st century, just as the

earlier scramble shaped the 19th. It will also become

a major epicenter for the ongoing competition between

the U.S. and China for economic and strategic

leadership.

Fortunately, the Trump administration understands the

stakes involved. Last week National Security Adviser

John Bolton gave a speech unveiling the

administration’s new Africa strategy. Unfortunately

for the U.S., China has a big lead in this

competition, and making up the difference won’t be

easy, even though it will have to be a critical part

of America’s 21st-century agenda.

But America has one clear advantage going forward.

Unlike the last scramble for Africa, in the 19th

century, when all the participants wound up being

imperialist bad actors, this scramble has two very

bad actors, Russia and China, and one clearly good

guy ready to ride to the rescue — namely, the U.S.

While China’s efforts in Africa have been brutal and

neo-colonialist in the extreme, we can, as Bolton

indicated in his speech, show sub-Saharan Africa’s 49

countries how to preserve their independence and

autonomy and become part of the modern economic order

in ways that benefit their people and increase their

prosperity and security — as well as the prosperity

and security of the United States.

Underlying all this is a fundamental reality: Africa

in the 21st century is going to be the next frontier

of globalization. It contains more than 30 percent of

world’s hydrocarbon reserves and minerals, including

rare earths essential for defense needs, and is

experiencing the world’s biggest population

explosion.

The United Nations estimates that Nigeria by 2050

will be the third-most populous country, after China

and India, and that Africa’s population as a whole

will surpass China’s by 2100. Of the world’s 21 most

“high fertility” nations — i.e., with the highest

potential for fast population growth — 19 are in

Africa.

Nor is Africa the economic basket case it once was.

According to the African Development Bank, subSaharan

Africa is poised to be the second-fastestgrowing

economy in the world, with a growth rate of

3.1 percent in 2018 and a projected growth rate of

3.6 percent in 2019–20. All this adds up to a

continent ready and eager to join the world’s

economic order.

Still, it’s easy to see why Africa slipped off

America’s strategic radar screen. Decades of poverty

and corruption have made Africa seem like the world’s

incurable basket case, an impression that the

unfolding AIDS crisis in the 1990s only reinforced.

The Obama years were wasted in terms of engagement in

Africa. While Obama made highly publicized trips to

Africa and paid lip service to the idea of helping

sub-Saharan Africa escape from poverty and join the

modern world, two predators took advantage of U.S.

passivity to plant themselves on the continent. The

first was radical Islam and Boko Haram. The other was

China.

While the U.S. and the rest of the West have largely

ignored Africa during the past two decades, China has

made it an economic and strategic priority. Beijing

sees it as the perfect hunting ground for securing

raw materials, for overseas business investment, and

above all for expanding China’s geopolitical

influence, as part of a grand strategy for replacing

the U.S. as the leading global hegemon.

By 2015 trade between China and Africa was close to

$300 billion. It now tops half a trillion dollars.

(By contrast, U.S. trade with Arica is barely $5

billion, and has been declining since 2011.) Right

now China has more than 3,000 infrastructure projects

underway across the continent and has handed out more

than $60 billion in commercial loans. But none of it,

especially the loans, comes without strings attached.

Hungry for economic opportunity, and hungry for cash,

one African country after another has willingly

turned itself into a Chinese dependency.

Dictatorships including those in Ethiopia and Ghana

have accepted Chinese help in erecting their own

versions of the Great Firewall, in order to gain

control of the Internet inside their borders, while

adopting the technologies of China’s high-tech police

state. Others fell for China’s offer of loans to

support those infrastructure projects and soon found

themselves in debt traps that they couldn’t escape —

and that China is able to use to wield political

influence.

Zambia is a perfect example. Today it finds itself in

debt to China in the amount of $6–10 billion — nearly

a third of its total GPD. Chinese control over the

country’s economy has put Zambia in a stranglehold.

As one former Zambian prime minister put it,

“European colonial exploitation in comparison with

Chinese exploitation appears benign,” the latter

being “focused on taking out of Africa as much as can

be taken out, without any regard for the welfare of

the local people.” Several other African countries,

including Rwanda and Ghana, could make the same

claim.

China’s growing influence has its military side as

well. China’s decision in 2017 to build a military

and naval base in Djibouti on the Horn of Africa has

been a geopolitical game-changer, given its proximity

to the U.S. base at Camp Lemonnier. The Djibouti base

location gives China’s new aircraft carriers a place

to rest and refit — and to project Chinese power

where no one ten or 20 years ago imagined it

possible.

Bolton in his speech mentioned both Zambia and

Djibouti, in explaining why America needs a new

proactive policy toward Africa, one that emphasizes

democracy, economic prosperity, and, above all,

political autonomy in face of China’s neo-colonialist

ambitions. While not forgetting the importance of the

war on radical Islam in Africa — which, we should

remember, the Obamas chose to fight largely with

hashtags — Bolton and the Trump administration

recognize that the top priority there is to counter

Russian and Chinese influence across the continent.

(China’s predatory practices get plenty of mention,

but Bolton also pointed out that Russia “continues to

sell arms and energy in exchange for votes at the

United Nations — votes that keep strongmen in power,

undermine peace and security, and run counter to the

best interests of the African people.”)

One component of the new American strategy is to look

for ways to increase investment by U.S. companies in

a broad range of industries, from energy and minerals

to telecommunications and health care. Another

component, just as important, of the the new U.S.

strategy is to cut and eliminate U.S. aid that only

strengthens corruption and economic dependence.

Between 1995 and 2006, for example, U.S. government

aid to Africa was roughly equal to the amount of

assistance provided by all other donors combined —

with little or no benefit for the intended

recipients, or for the U.S. The new Trump policy will

aim to ensure, instead, according to Bolton, “that

ALL aid to the region — whether for security,

humanitarian, or development needs — advances US

interests.”

Finally, the new U.S. policy will stress engagement

through bilateral ties with individual African states

instead of reliance on multilateral bodies such as

the World Bank and the U.N. The U.N.’s human-rights

record in its African peacekeeping missions, for

example, has been horrendous and has only played into

China’s pose as Africa’s last best hope.

All this represents a breath of fresh air in

America’s policy toward Africa and gives us an

important, benign and active role in the coming

scramble for Africa that will dominate much of the

21st century. Will that competition lead to greatpower

tensions like those of the 19th century? Not if

the U.S., unlike China, which treats African

countries as neo-colonial dependents, invites African

countries to be partners in a new order for the subSaharan

region — and for the United States.

In end, how ironic will it be that while President

Obama, who proudly touted his African heritage,

allowed Russian and Chinese malign influence — as

well as that of ISIS and Boko Haram — to grow in

Africa. Donald Trump, the man whom the media and

liberals and some conservatives paint as a racist, is

the one on course to become the liberator of Africa

from Chinese neo-colonialism and to set the continent

on the path to peace and prosperity at long last.

Jimmy Carter on USA, China, and Africa

Washington Post, Dec. 31, 2018

http://tinyurl.com/y8b84jvg

"The United States should return to the Paris climate

accord and work with China on environmental and

climate-change issues, as the epic struggle against

global warming requires active participation from

both nations. But I believe the easiest route to

bilateral cooperation lies in Africa. Both countries

are already heavily involved there in fighting

disease, building infrastructure and keeping peace —

sometimes cooperatively. Yet each nation has accused

the other of economic exploitation or political

manipulation. Africans — like billions of other

people around the world — do not want to be forced to

choose a side. Instead, they welcome the synergy that

comes from pooling resources, sharing expertise and

designing complementary aid programs. By working

together with Africans, the United States and China

would also be helping themselves overcome distrust

and rebuild this vital relationship."

Trump’s Africa strategy should have cast China as a

regional partner, not a global adversary

December 17, 2018

John J Stremlau

Visiting Professor of International Relations,

University of the Witwatersrand

University of the Witwatersrand provides support as a

hosting partner of The Conversation Africa.

https://theconversation.com/africa

https://allafrica.com/stories/201812180581.html

US President Donald Trump has finally approved a “New

Africa Strategy”. His national security adviser, John

Bolton, described the contents on 13 December at the

conservative Heritage Foundation in Washington. He

began positively, declaring that:

lasting stability, prosperity, independence and

security on the African continent are in the national

security interest of the United States.

But he then went on to ignore Africa’s own efforts to

address these broad challenges, including its

multilateral initiatives. Instead, Bolton’s

announcement was replete with rhetoric reminiscent of

the Cold War.

The new strategy makes one thing clear: what really

matters to Trump is not Africa but containing and

countering China.

The reaction from an African perspective is likely be

bemusement rather than surprise. Trump has shown

little interest or empathy towards Africa. And much

enmity toward China. His Africa strategy ignores two

decades of complex – but generally positive –

reactions across sub-Saharan Africa to China becoming

the region’s biggest trading partner and a major

source of aid and investment.

Previous US administrations generally welcomed

Chinese engagement in Africa. Bolton, however,

alleged that:

China uses bribes, opaque agreements, and the

strategic use of debt to hold states in Africa

captive to Beijing’s wishes and demands.

But does it need to be this way? I would argue not.

Africa offers China and America an opportunity to

demonstrate to the world – and to each other – that

their competition can be constructive with Africa

playing a moderating influence by brokering an agreed

trilateral agenda.

We need to explore ways to advance cooperation

between Africa, China and the US as a confidence

building measure in relations between the US and

China. This would obviously need to be designed for

the primary benefit of African partners.

Testing trilateralism

Collaborative projects that involve the US and China,

with Africa in the forefront, have been the focus of

a Carter Centre project since 2014. The centre’s many

successful programs in Africa, especially public

health, have generated high-level trilateral policy

interest. Since the Trump administration took over,

these conversations have excluded his senior

advisors. Nevertheless, work has continued. This has

included recent developments which suggest headway is

being made.

In early December the South African Institute of

International Affairs hosted the troika that leads

this project. The troika was represented by Seyoum

Mesfin, Ethiopia’s former and longest-serving foreign

minister, an ambassador to China, and regional

mediator in Sudan; Zhong Jianhua, formerly China’s

Special Representative on African affairs and to the

Sudan conflicts; and Donald Booth, a former US

ambassador to Liberia, Zambia, Ethiopia and special

envoy to Sudan/South Sudan.

Three dozen African, Chinese and US scholars as well

as policy experts contributed their analyses of

previous and possible future areas for trilateral

cooperation. They drew on some recent examples. These

included efforts to combat piracy off the Horn of

Africa and Gulf of Guinea as well as jointly

developing a university campus in Liberia. Other

projects have involved coordinated mediation between

Sudan and South Sudan and mutually reinforcing

actions to deal with the Ebola epidemic in West

Africa.

Challenges ahead

Several priority areas for future tri-lateral

cooperation were identified.

One was the recently constructed headquarters for the

Centre for Disease Control and Prevention in Addis

Ababa. Funded by China, the next priority for

trilateral cooperation is to ensure the centre is

equipped to provide better early warning and response

to threats like Ebola.

Another priority area is expanding economic aid,

trade and investment. This could be done through

trilateral projects funded under China’s “Belt and

Road” initiative and the US Build Act. The act was

approved in October by a large bi-partisan majority

of the US Congress.

A related issue is the huge loss of vital tax revenue

to African governments due to huge “illicit financial

flows”. These are estimated to exceed annual inflows

of foreign assistance. The project will seek ways to

encourage US and China to support the work of a panel

set up by African Union and United Nations Economic

Commission for Africa.

Two other broad areas for potential trilateral

cooperation are sustainable agriculture and energy.

Two initiatives started by the Obama Administration,

with the support of Congress, have become popular in

Africa. These are the “Feed the Future” and “Power

Africa”.

Trump has long wanted to cut both. But his negative

attitude isn’t shared by the US Congress, and perhaps

even key members of his administration. Assistant

Secretary of State for Africa, Tibor Nagy, summarised

US-Africa policy before the House Foreign Affairs

Committee on the same day Trump approved the new

Africa strategy. Nagy’s comments reflected a

different mindset. He spoke positively about the two

Obama initiatives. He also didn’t seem alarmed by

China’s growing presence.

At a time when many in Africa are debating how to

build capable states without the undesirable aspects

of either America’s “decadent” democracy or China’s

“responsive” authoritarianism, engaging both should

yield important insights for advancing collective

self-reliance and development.

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic

publication providing reposted commentary and

analysis on African issues, with a particular focus

on U.S. and international policies. AfricaFocus

Bulletin is edited by William Minter.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at

africafocus@igc.org. Please write to this address to

suggest material for inclusion. For more information

about reposted material, please contact directly the

original source mentioned. For a full archive and

other resources, see http://www.africafocus.org

|