|

Algeria

Angola

Benin

Botswana

Burkina Faso

Burundi

Cameroon

Cape Verde

Central Afr. Rep.

Chad

Comoros

Congo (Brazzaville)

Congo (Kinshasa)

Côte d'Ivoire

Djibouti

Egypt

Equatorial Guinea

Eritrea

Ethiopia

Gabon

Gambia

Ghana

Guinea

Guinea-Bissau

Kenya

Lesotho

Liberia

Libya

Madagascar

Malawi

Mali

Mauritania

Mauritius

Morocco

Mozambique

Namibia

Niger

Nigeria

Rwanda

São Tomé

Senegal

Seychelles

Sierra Leone

Somalia

South Africa

South Sudan

Sudan

Swaziland

Tanzania

Togo

Tunisia

Uganda

Western Sahara

Zambia

Zimbabwe

|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

USA/Africa: From Wakanda to Reparations, Part 2

AfricaFocus Bulletin

February 26, 2019 (190226)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

“Just as cotton, and with it slavery, became key to the U.S.

economy, it also moved to the center of the world economy and its

most consequential transformations: the creation of a globally

interconnected economy, the Industrial Revolution, the rapid

spread of capitalist social relations in many parts of the world,

and the Great Divergence—the moment when a few parts of the world

became quite suddenly much richer than every other part.” - Sven

Beckert

Part 1 of this AfricaFocus Bulletin series, available at

http://www.africafocus.org/docs19/usa1902a.php, featured excerpts

from several thought-provoking commentaries on the film Black

Panther. This second part features brief descriptions of links to

longer non-fiction articles and books exploring the historical

questions raised in greater depth.

What you will find below is a select list, with brief

descriptions, of key readings on the US-African relationship in

world historical context, centering race and the impact of the

last 500 years of world history on the present. The list includes

four new paradigm-shifting histories, as well as four classic

works that have centered the same themes. It also includes several

recent readings on slavery, the genocidal conquest of the

Americas, the slave trade, and the issues of reparations or

redress for historical crimes.

Although reparations has long been a demand of activists (see

https://www.ncobraonline.org/reparations/ for background), it is

now beginning to enter a much wider public debate. These readings

will help put this growing debate in context.

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on the USA and Africa, visit

http://www.africafocus.org/country/usa-africa.php

Recent articles on reparations in public debate include:

Washington Post, “Three 2020 Democrats say ‘yes’ to race-based

reparations — but remain vague on details,” Feb. 22, 2019

http://tinyurl.com/y3axvl2u

William J. Barber II, “How Ralph Northam and others can repent of

America’s original sin,” Washington Post, Feb. 7, 2019

http://tinyurl.com/y245x3kv

Text of the most recent version of H.R. 40 (Commission to Study

and Develop Reparation Proposals for African-Americans Act),

introduced on January 3, 2019, by Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee and 23

co-sponsors.

http://tinyurl.com/y2mev8e6

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

Four New Histories

If you want well-written path-breaking overviews of US history

placing it in the context of race and the last 500 years of world

history, these four recent books should be at the top of your

reading list.

“This may well be the most important US history book you will read

in your lifetime. If you are expecting yet another ‘new’ and

improved historical narrative or synthesis of Indians in North

America, think again. Instead Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz radically

reframes U.S. history, destroying all foundation myths to reveal a

brutal settler colonial structure and ideology designed to cover

its bloody tracks. Here, rendered in honest, often poetic words,

is the story of those tracks and the people who survived—bloodied

but unbowed. Spoiler alert: the colonial era is still here, and so

are the Indians.” —Robin D. G. Kelley

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

[From review by Catherine Lizette Gonzalez in Colorlines, Feb. 2,

2018 http://tinyurl.com/y4hw6bcf]

Dominant narratives about United States’ history will usually wax

nostalgic for the patriots who fought for liberty and

egalitarianism during the American Revolution. But, arguably,

those liberal ideals were never really meant to serve anyone but

White settlers. Even today, ideas of American exceptionalism—like

President Donald Trump’s “America First” agenda—are largely

weaponized against communities of color.

In his new book, “An African American and Latinx History of the

United States,” historian Paul Ortiz challenges these dominant

narratives by placing African Americans and Latinx people at the

center of U.S. history.

Ortiz illuminates how Black and Brown people built multiracial

movements through the 1700s to the 21st Century to achieve civil

and democratic rights. In the book, the author and professor of

history at the University of Florida, argues that African American

and Latinx activists were inspired by what he’s coined as

”emancipatory internationalism” or the longstanding rejection of

Eurocentric philosophies of liberty in exchange for the freedom

struggles of the Global South.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Nikhil Pal Singh argues that the United States’ pursuit of war

since the September 11 terrorist attacks has reanimated a longer

history of imperial statecraft that segregated and eliminated

enemies both within and overseas. America’s territorial expansion

and Indian removals, settler in-migration and nativist

restriction, and African slavery and its afterlives were formative

social and political processes that drove the rise of the United

States as a capitalist world power long before the onset of

globalization.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Daniel Immerwahr, How to Hide an Empire: A Short

History of the Greater United States by Daniel Immerwahr, 2019.

https://bookshop.org/a/709/9780374172145

The author explains briefly in an Feb. 15 article in The Guardian (

http://tinyurl.com/y6nk7x63).

What this map shows is the country’s full territorial extent: the

“Greater United States”, as some at the turn of the 20th century

called it. In this view, the place normally referred to as the US

– the logo map – forms only a part of the country. A large and

privileged part, to be sure, yet still only a part. Residents of

the territories often call it the “mainland”.

On this to-scale map, Alaska isn’t shrunken down to fit into a

small inset, as it is on most maps. It is the right size – ie,

huge. The Philippines, too, looms large, and the Hawaiian island

chain – the whole chain, not just the eight main islands shown on

most maps – if superimposed on the mainland would stretch almost

from Florida to California.

Four Classic Works

These four books feature structural analysis and foreground

resistance as well as oppression, providing clear alternative

frameworks to understanding African, global, and U.S. History.

All of these are still in print, and available in Kindle as well

as paperback editions. If your public or school library does not

have copies, encourage it to make sure they get these fundamental

works.

W. E. B. Du Bois, The World and Africa, 1946.

http://amzn.to/2oZAjCX

Slavery in the United States

The catchphrase of slavery as "America's original sin" is

commonplace. The role of slavery in shaping the contours of

American society and the global economy, now commonly recognized

by scholars, is much less widely acknowledged. But the effects of

slavery are definitely not only in the past, as noted by the

Southern Poverty Law Center in the report quoted below.

The remaining links here provide entry points to the work of Sven

Beckert, Edward E. Baptist, and Daine Ramey Berry, three leading

scholars whose recent publications are shaping the current

understanding of how slavery led not only to the poverty of those

who were enslaved but also built the wealth now disproportionately

held by a small minority. As Beckert in particular stresses, the

systemwas not only national but global.

Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), Teaching the Hard History of

American Slavery, January 2018.

https://www.splcenter.org/20180131/teaching-hard-history

It is often said that slavery was our country’s original sin, but

it is much more than that. Slavery is our country’s origin. It was

responsible for the growth of the American colonies, transforming

them from far-flung, forgotten outposts of the British Empire to

glimmering jewels in the crown of England. And slavery was a

driving power behind the new nation’s territorial expansion and

industrial maturation, making the United States a powerful force

in the Americas and beyond.

Slavery was also our country’s Achilles' heel, responsible for its

near undoing. When the southern states seceded, they did so

expressly to preserve slavery. So wholly dependent were white

Southerners on the institution that they took up arms against

their own to keep African Americans in bondage. They simply could

not allow a world in which they did not have absolute authority to

control black labor—and to regulate black behavior.

The central role that slavery played in the development of the

United States is beyond dispute. And yet, we the people do not

like to talk about slavery, or even think about it, much less

teach it or learn it. The implications of doing so unnerve us.

...

Understanding American slavery is vital to understanding racial

inequality today. The formal and informal barriers to equal rights

erected after emancipation, which defined the parameters of the

color line for more than a century, were built on a foundation

constructed during slavery. Our narrow understanding of the

institution, however, prevents us from seeing this long legacy and

leads policymakers to try to fix people instead of addressing the

historically rooted causes of their problems.

Sven Beckert, "Slavery and Capitalism," Chronicle of Higher

Education, December 12, 2014.

https://www.chronicle.com/article/SlaveryCapitalism/150787

Sven Beckert, Empire of Cotton: A Global History, 2014.

https://bookshop.org/a/709/9780375713965

For too long, many historians saw no problem in the opposition

between capitalism and slavery. They depicted the history of

American capitalism without slavery, and slavery as

quintessentially noncapitalist. Instead of analyzing it as the

modern institution that it was, they described it as premodern:

cruel, but marginal to the larger history of capitalist modernity,

an unproductive system that retarded economic growth, an artifact

of an earlier world. Slavery was a Southern pathology, invested in

mastery for mastery’s sake, supported by fanatics, and finally

removed from the world stage by a costly and bloody war.

Some scholars have always disagree with such accounts. In the

1930s and 1940s, C.L.R. James and Eric Williams argued for the

centrality of slavery to capitalism, though their findings were

largely ignored. Nearly half a century later, two American

economists, Stanley L. Engerman and Robert William Fogel, observed

in their controversial book Time on the Cross (Little, Brown,

1974) the modernity and profitability of slavery in the United

States. Now a flurry of books and conferences are building on

those often unacknowledged foundations. They emphasize the dynamic

nature of New World slavery, its modernity, profitability,

expansiveness, and centrality to capitalism in general and to the

economic development of the United States in particular.

…

Just as cotton, and with it slavery, became key to the U.S.

economy, it also moved to the center of the world economy and its

most consequential transformations: the creation of a globally

interconnected economy, the Industrial Revolution, the rapid

spread of capitalist social relations in many parts of the world,

and the Great Divergence—the moment when a few parts of the world

became quite suddenly much richer than every other part. The

humble fiber, transformed into yarn and cloth, stood at the center

of the emergence of the industrial capitalism that is so familiar

to us today. Our modern world originates in the cotton factories,

cotton ports, and cotton plantations of the 18th and 19th

centuries. The United States was just one nexus in a much larger

story that connected artisans in India, European manufacturers,

and, in the Americas, African slaves and land-grabbing settlers.

It was those connections, over often vast distances, that created

an empire of cotton—and with it modern capitalism.

Edward E. Baptist, The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the

Making of American Capitalism, 2014.

https://bookshop.org/a/709/9780465049660

Baptist argues that our understanding — or misunderstanding — of

slavery has policy implications for the present. (In that way, the

book is complementary reading to Ta-Nehisi Coates’ much talked about

Case For Reparations). “If slavery was outside of US

history, for instance — if indeed it was a drag and not a rocket

booster to American economic growth — then slavery was not

implicated in US growth, success, power and wealth,” Baptist

writes. “Therefore none of the massive quantities of wealth and

treasure piled by that economic growth is owed to African

Americans.” Anyone who believes that, his book aims to show,

really hasn’t heard the half of it. Braden Boyette, Huffington

Post, Oct. 23, 2014, “A Short Guide To ‘The Half Has Never Been

Told’" - http://tinyurl.com/y4o569po

Daina Ramey Berry, The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value

of the Enslaved, from Womb to Grave, in the Building of a Nation,

2017.

https://bookshop.org/a/709/9780807067147

n life and in death, slaves were commodities, their monetary value

assigned based on their age, gender, health, and the demands of

the market. The Price for Their Pound of Flesh is the first book

to explore the economic value of enslaved people through every

phase of their lives—including preconception, infancy, childhood,

adolescence, adulthood, the senior years, and death—in the early

American domestic slave trade. Covering the full “life cycle,”

historian Daina Ramey Berry shows the lengths to which enslavers

would go to maximize profits and protect their investments.

Illuminating “ghost values” or the prices placed on dead enslaved

people, Berry explores the little-known domestic cadaver trade and

traces the illicit sales of dead bodies to medical schools.

This book is the culmination of more than ten years of Berry’s

exhaustive research on enslaved values, drawing on data unearthed

from sources such as slave-trading records, insurance policies,

cemetery records, and life insurance policies. Writing with

sensitivity and depth, she resurrects the voices of the enslaved

and provides a rare window into enslaved peoples’ experiences and

thoughts, revealing how enslaved people recalled and responded to

being appraised, bartered, and sold throughout the course of their

lives. Reaching out from these pages, they compel the reader to

bear witness to their stories, to see them as human beings, not

merely commodities.

Conquest of the Americas

“European colonization of Americas killed so many it cooled

Earth's climate,” Guardian, Jan. 31, 2019

http://tinyurl.com/y7pg5x66

Settlers killed off huge numbers of people in conflicts and also

by spreading disease, which reduced the indigenous population by

90% in the century following Christopher Columbus’s initial

journey to the Americas and Caribbean in 1492.

This “large-scale depopulation” resulted in vast tracts of

agricultural land being left untended, researchers say, allowing

the land to become overgrown with trees and other new vegetation.

The regrowth soaked up enough carbon dioxide from the atmosphere

to actually cool the planet, with the average temperature dropping

by 0.15C in the late 1500s and early 1600s, the study by

scientists at University College London found.

“The great dying of the indigenous peoples of the Americas

resulted in a human-driven global impact on the Earth system in

the two centuries prior to the Industrial Revolution,” wrote the

UCL team of Alexander Koch, Chris Brierley, Mark Maslin and Simon

Lewis.

The UCL researchers found that the European colonization of the

Americas indirectly contributed to this colder period by causing

the deaths of about 56 million people by 1600 [leaving only about

1 in 10 of the pre-colonization population]. The study attributes

the deaths to factors including introduced disease, such as

smallpox and measles, as well as warfare and societal collapse.

Full study available at http://tinyurl.com/yceyeqbj

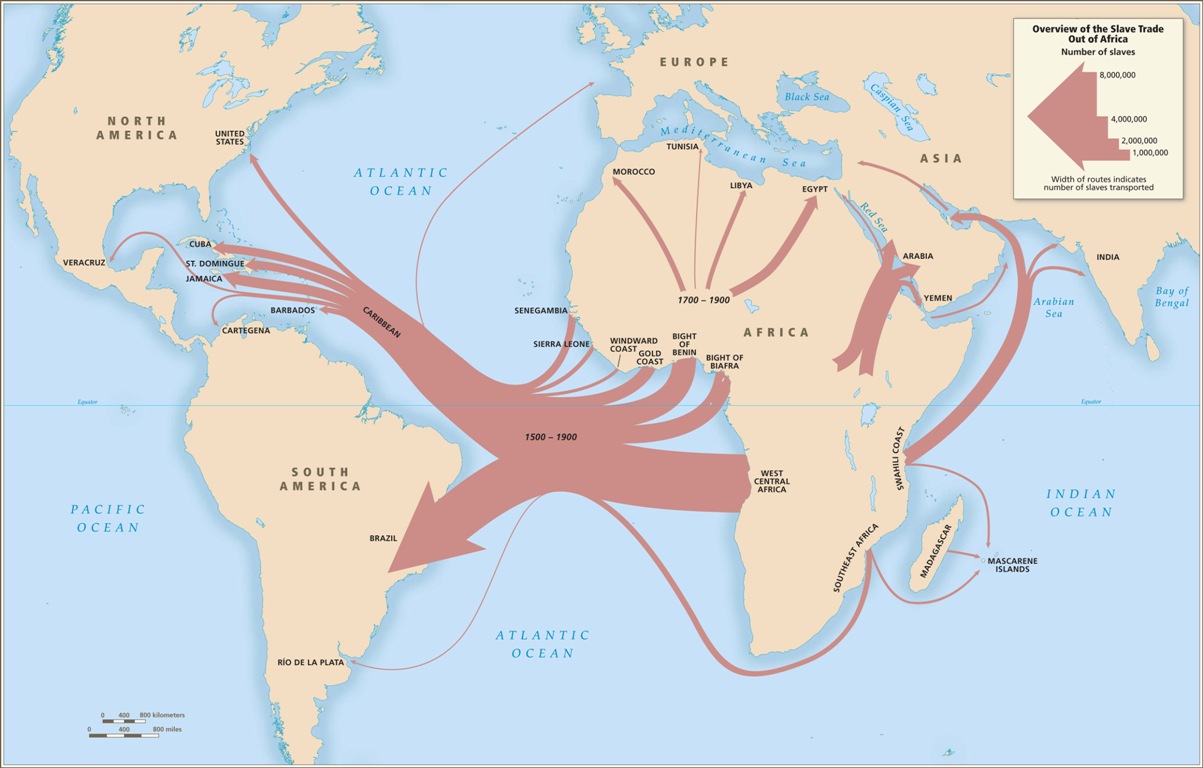

The Atlantic Slave Trade

The transcontinental scope of slavery is most clearly visible in

the Atlantic slave trade, which over centuries brought over 10

million enslaved Africans to the Americas. Strikingly, the vast

majority were brought not to the United States but to Brazil and

the Caribbean, as illustrated in the map below and related links.

The Atlantic Slave Trade in Two Minutes

Animated map: 315 years. 20,528 voyages. Millions of lives.

http://tinyurl.com/p3npfu5

Slave Voyages: Introductory Maps

http://www.slavevoyages.org/assessment/intro-maps

Among the host of books on the slave trade, The Atlantic Slave

Trade (2010, https://bookshop.org/a/709/9780521182508) by Herbert Klein provides an

accessible summary of current scholarship. Joseph Miller's Way of

Death: Merchant Capitalism and the Angolan Slave Trade, 1730-1830

(1988, https://bookshop.org/a/709/9780299115647) is a dense read, but an unequalled

account of how the intertwined economies reaching from Angola to

Brazil, Portugal, and England extracted profits from the lives and

deaths of those enslaved.

Reparations

Reparations for slavery and the slave trade is often debated in

simplistic terms, as if it were only a question of the feasibility

of payments to individuals and as if it only applied to the United

States. And while reparations is most frequently and legitimately

used to refer specifically to slavery and the slave trade, given the magnitude

of those centuries-long crimes, the concept is also a more

general one in human rights discourse, applicable to more recent

crimes perpetrated on specific living individuals and communities.

The following five readings are useful to expand the discussion.

Two focus on the United States, while two expand the discussion

beyond the borders of the United States. And a fifth, on redress

for historical crimes against Native American communities,

stresses that monetary compensation is much too limited a concept

to cover the actions needed.

Ta-Nehisi Coates, "The Case for Reparations," The Atlantic, June

2014.

http://tinyurl.com/h9lezog

And so we must imagine a new country. Reparations—by which I mean

the full acceptance of our collective biography and its

consequences—is the price we must pay to see ourselves squarely.

The recovering alcoholic may well have to live with his illness

for the rest of his life. But at least he is not living a drunken

lie. Reparations beckons us to reject the intoxication of hubris

and see America as it is—the work of fallible humans.

Won’t reparations divide us? Not any more than we are already

divided. The wealth gap merely puts a number on something we feel

but cannot say—that American prosperity was ill-gotten and

selective in its distribution. What is needed is an airing of

family secrets, a settling with old ghosts. What is needed is a

healing of the American psyche and the banishment of white guilt.

What I’m talking about is more than recompense for past

injustices—more than a handout, a payoff, hush money, or a

reluctant bribe. What I’m talking about is a national reckoning

that would lead to spiritual renewal. Reparations would mean the

end of scarfing hot dogs on the Fourth of July while denying the

facts of our heritage. Reparations would mean the end of yelling

“patriotism” while waving a Confederate flag. Reparations would

mean a revolution of the American consciousness, a reconciling of

our self-image as the great democratizer with the facts of our

history.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Flint Taylor "How Activists Won Reparations for the Survivors of

Chicago Police Department Torture," In These Times, June 26, 2015.

http://tinyurl.com/y29xexv9

The 20-year reign of police torture that was orchestrated by

Commander Jon Burge—and implicated former Mayor Richard M. Daley

and a myriad of high ranking police and prosecutorial

officials—has haunted Chicago for decades. … Finally, on May 6,

2015, in response to a movement that has spanned a generation, the

Chicago City Council formally recognized this sordid history by

passing historic legislation that provides reparations to the

survivors of police torture in Chicago.

…

Over the course of the struggle, the movement had once again

looked internationally both for support and for examples—Chile,

Argentina and South Africa, to name three. The examples here in

the U.S. were precious few: Japanese-Americans who were interned

during World War II, the descendants of the African-American

victims of the deadly 1923 race riot in Rosewood, Florida and the

victims of the mass sterilizations in North Carolina. The movement

was also inspired by the continuing struggle for reparations for

enslaved African Americans, the movement to fully document and

memorialize lynchings in the South, by Black People Against Police

Torture and the Midwest Coalition for Human Rights, and, most

importantly, by the survivors of Chicago police torture and their

families.

While full compensation for the pain suffered at the hands of the

torturers was not (and could not be) obtained—a reality that was

pointed out in a Sun-Times editorial that otherwise commended the

historic accomplishment—the reparations package is both

symbolically and in fact substantial and unique, particularly

given that the survivors had no legal recourse.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Lord Anthony Gifford, "The Legal Basis of the Claim for

Reparations," Paper presented to Pan African Congress on

Reparations, Abuja, Nigeria, April 27-29, 1993.

http://www.shaka.mistral.co.uk/legalbasis.htm

See also the Abuja Declaration from that Congress at

http://tinyurl.com/yynw8sne

[summary of points]

- The enslavement of Africans was a crime against humanity

- International law recognises that those who commit crimes

against humanity must make reparation

- There is no legal, barrier to prevent those who still suffer

the consequences of crimes against humanity from claiming

reparations, even though the crimes were committed against their

ancestors

- The claim would be brought on behalf of all Africans, in Africa

and in the Diaspora, who suffer the consequences of the crime,

through the agency of an appropriate representative body

- The claim would be brought against the governments of those

counties which promoted and were enriched by the African slave

trade and the institution of slavery

- The amount of the claim would be assessed by experts in each

aspect of life and in each region, affected by the institution of

slavery

- The claim, if not settled by agreement, would ultimately be

determined by a special international tribunal recognised by all

parties

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Ana Lucia Araujo, Reparations for Slavery and the Slave Trade: A

Transnational and Comparative History, 2017.

http://amzn.to/2FE5pJV

Slavery and the Atlantic slave trade are among the most heinous

crimes against humanity committed in the modern era. Yet, to this

day no former slave society in the Americas has paid reparations

to former slaves or their descendants. European countries have

never compensated their former colonies in the Americas, whose

wealth relied on slave labor, to a greater or lesser extent.

Likewise, no African nation ever obtained any form of reparations

for the Atlantic slave trade.

Ana Lucia Araujo argues that these calls for reparations are not

only not dead, but have a long and persevering history. She

persuasively demonstrates that since the 18th century, enslaved

and freed individuals started conceptualizing the idea of

reparations in petitions, correspondences, pamphlets, public

speeches, slave narratives, and judicial claims, written in

English, French, Spanish, and Portuguese. In different periods,

despite the legality of slavery, slaves and freed people were

conscious of having been victims of a great injustice.

This is the first book to offer a transnational narrative history

of the financial, material, and symbolic reparations for slavery

and the Atlantic slave trade. Drawing from the voices of various

social actors who identified themselves as the victims of the

Atlantic slave trade and slavery, Araujo illuminates the multiple

dimensions of the demands of reparations, including the period of

slavery, the emancipation era, the post-abolition period, and the

present.

Bradford, William, "Beyond Reparations: An American Indian Theory

of Justice" (2004). Aboriginal Policy Research Consortium

International (APRCi). 217.

https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/aprci/217

A significant element in the slavery reparations claim is the lost

value consequence of the unpaid labor extracted from slave

ancestors, and thus it is logical that, with few

exceptions, proponents of slavery reparations equate the remedy

with financial compensation. Although money cannot undo history,

it can ameliorate the socioeonomic conditions of the descendants

of former slaves, and money is the lodestar of most

reparationists.

However, justice is not a one-size-fits-all commodity ...

Slavery is not the sole, nor the first, nor even, arguably, the

most egregious historical injustice for which

the U.S. bears responsibility.

…

Although compensation may well be the proper form redress should

assume in relation to the crime of African American slavery,

reparations is ill-suited as a remedy around which to construct a

theory of justice for Indians, not because of the social

resistance it would be likely to engender, but because money

simply cannot reach, let alone repair, land theft, genocide,

ethnocide, and, above all, the denial of the fundamental right to

self-determination. Only a committed and holistic program of legal

reformation as the capstone in a broader structure of remedies,

including the restoration of Indian lands and the reconciliation

between Indian and non-Indian peoples, can satisfy the

preconditions for justice for the original peoples of the U.S.

For a broader view of international developments on the rights of

indigenous people, including the roles of redress and

compensation, see The United Nations Declaration on the Rights

of Indigenous Peoples: A Manual for National Human Rights

Institutions. Asia Pacific Forum of National Human Rights

Institutions and the Office of the United Nations

High Commissioner for Human Rights. 2013.

http://tinyurl.com/y4cvv766

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication

providing reposted commentary and analysis on African issues, with

a particular focus on U.S. and international policies. AfricaFocus

Bulletin is edited by William Minter.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please

write to this address to suggest material for inclusion. For more

information about reposted material, please contact directly the

original source mentioned. For a full archive and other resources,

see http://www.africafocus.org

|