|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

USA/Global: Millions Displaced by US Post-9/11 Wars

AfricaFocus Bulletin

September 28, 2020 (2020-09-28)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

“Wartime displacement (alongside war deaths and injuries) must be

central to any analysis of the post-9/11 wars and their short- and

long-term consequences. Displacement also must be central to any

possible consideration of the future use of military force by the

United States or others. Ultimately, displacing 37 million—and

perhaps as many as 59 million—raises the question of who bears

responsibility for repairing the damage inflicted on those

displaced.” - Brown University Costs of War Project

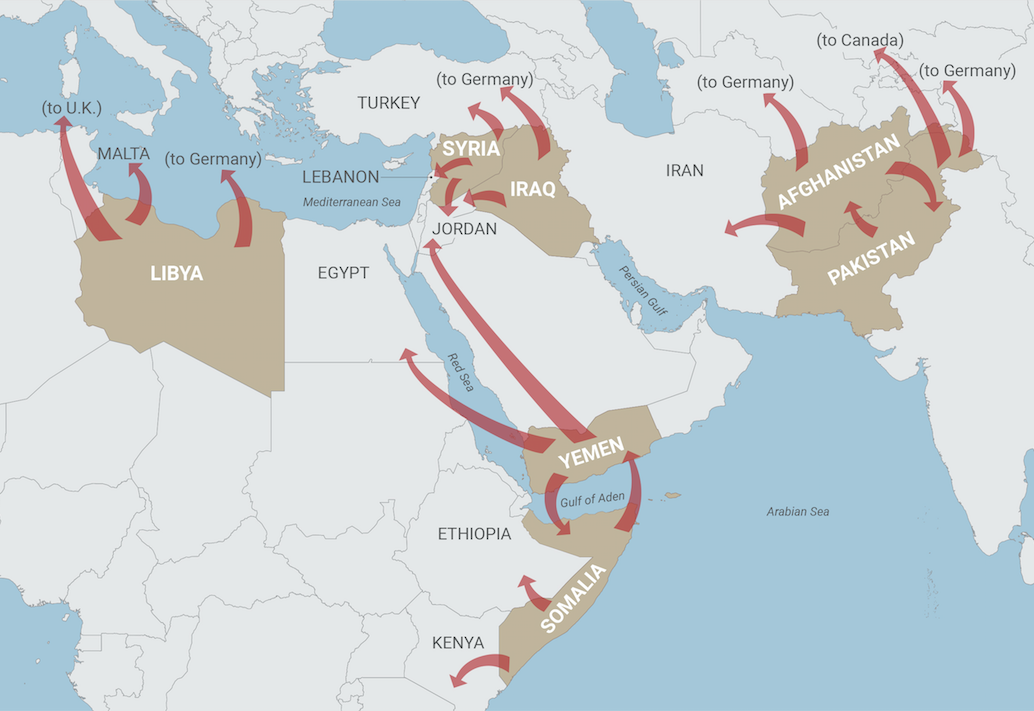

This AfricaFocus Bulletin contains excerpts from this new report documenting one large part of the damage from wars in which the United States has played a major role in the post 9/11 period. The calculation includes refugees and internally displaced from 8 countries: Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, the Philippines, Libya, and Syria. The excerpts below include the sections on Somalia and Libya. The full report, including charts and a full methodological appendix, is available at https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/costs/human/refugees.

Also included below is the latest essay by William Minter and Imani Countess, entitled “Overhauling U.S. Foreign Policy.” This essay, which appeared first in Organizing Upgrade on September 22, builds on a multipart essay series entitled Beyond Eurocentrism and U.S. Exceptionalism.

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on peace and security, visit

http://www.africafocus.org/intro-peace.php.

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on migration, visit

http://www.africafocus.org/migrexp.php.

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

Creating Refugees: Displacement Caused by the United States’ Post-9/11 Wars

David Vine, Cala Coffman, Katalina Khoury, Madison Lovasz, Helen Bush, Rachel Leduc, and Jennifer Walkup

September 8, 2020

Costs of War Project, Brown University

https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/costs/human/refugees

Executive Summary

Since President George W. Bush announced a “global war on terror”

following Al Qaeda’s September 11, 2001 attacks on the United

States, the U.S. military has engaged in combat around the world.

As in past conflicts, the United States’ post-9/11 wars have

resulted in mass population displacements. This report is the first

to measure comprehensively how many people these wars have

displaced. Using the best available international data, this report

conservatively estimates that at least 37 million people have fled

their homes in the eight most violent wars the U.S. military has

launched or participated in since 2001. The report details a

methodology for calculating wartime displacement, provides an

overview of displacement in each war-affected country, and points

to displacement’s individual and societal impacts.

Wartime displacement (alongside war deaths and injuries) must be

central to any analysis of the post-9/11 wars and their short- and

long-term consequences. Displacement also must be central to any

possible consideration of the future use of military force by the

United States or others. Ultimately, displacing 37 million—and

perhaps as many as 59 million—raises the question of who bears

responsibility for repairing the damage inflicted on those

displaced.

Major Findings

§ The U.S. post-9/11 wars have forcibly displaced at least 37

million people in and from Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Yemen,

Somalia, the Philippines, Libya, and Syria. This exceeds those

displaced by every war since 1900, except World War II.

§ Millions more have been displaced by other post-9/11 conflicts

involving U.S. troops in smaller combat operations, including in:

Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic

Republic of the Congo, Mali, Niger, Saudi Arabia, and Tunisia.

§ 37 million is a very conservative estimate. The total displaced

by the U.S. post-9/11 wars could be closer to 48–59 million.

§ 25.3 million people have returned after being displaced,

although return does not erase the trauma of displacement or mean

that those displaced have returned to their original homes or to a

secure life.

§ Any number is limited in what it can convey about displacement’s

damage. The people behind the numbers can be difficult to see, and

numbers cannot communicate how it might feel to lose one’s home,

belongings, community, and much more. Displacement has caused

incalculable harm to individuals, families, towns, cities, regions,

and entire countries physically, socially, emotionally, and

economically.

The U.S. post-9/11 wars have displaced at least 37 million people in and from eight countries: Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, the Philippines, Libya, and Syria.

Introduction

Since the George W. Bush administration launched a “global war on

terror” following Al Qaeda’s September 11, 2001 attacks on the

United States, the U.S. military has waged war continuously for

almost two decades.2 In that time, U.S. forces have fought in wars

or participated in other combat operations in at least 24

countries.3 The destruction inflicted by warfare in these countries

has been incalculable for civilians and combatants, for U.S.

military personnel and their family members, and for entire

societies. Deaths and injuries number in the millions. Like other

wars throughout history, the U.S. post-9/11 wars have caused

millions of people—the vast majority, civilians—to fear for their

lives and flee in search of safety. Millions have fled air strikes,

bombings, artillery fire, drone attacks, gun battles, and rape.

People have fled the destruction of their homes, neighborhoods,

hospitals, schools, jobs, and local food and water sources. They

have escaped forced evictions, death threats, and large-scale

ethnic cleansing set off by the U.S wars in Afghanistan and Iraq in

particular.4

To our knowledge, no one has calculated how many people have been

displaced by the United States’ post-9/11 wars. Some scholars,

journalists, and international organizations have provided

displacement data for some of these wars, such as those in

Afghanistan and Iraq. However these statistics tend to be snapshots

of the number of refugees and internally displaced people (IDP) at

a particular point in time rather than a full accounting

of the total number of people displaced over time since

the start of the wars.

This paper calculates the total number of displaced people in the

eight post-9/11 wars in which U.S. forces have been most

significantly involved. We focus on wars where the U.S. government

bears a clear responsibility for initiating armed combat (the

overlapping Afghanistan/Pakistan war and the post-2003 war in

Iraq); for escalating armed conflict (U.S. and European

intervention in the Libyan uprising against Muammar Gaddafi and

Libya’s ongoing civil war and U.S. involvement in Syria); or for

being a significant participant in combat through drone strikes,

battlefield advising, logistical support, arms sales, and other

means (U.S. forces’ involvement in wars in Yemen, Somalia, and the

Philippines).

In documenting displacement caused by the U.S. post-9/11 wars, we

are not suggesting the U.S. government or the United States as a

country is solely responsible for the displacement. Causation is

never so simple. Causation always involves a multiplicity of

combatants and other powerful actors, centuries of history, and

large-scale political, economic, and social forces. Even in the

simplest of cases, conditions of pre-existing poverty,

environmental change, prior wars, and other forms of violence shape

who is displaced and who is not.

This paper and its accompanying tables document several categories

of people displaced by the post-9/11 wars: 1) refugees, 2) asylum

seekers pursuing protection as refugees, and 3) internally

displaced persons or people (IDPs). We also calculate the number of

4) refugees, asylum seekers, and IDPs who have returned to their

country or area of origin.

Ultimately, we estimate that at least 37 million people have been

displaced in just eight countries since 2001 (Table 1). This

includes 8 million people displaced across international borders as

refugees and asylum seekers and 29 million people displaced

internally to other parts of their countries. To put these figures

in perspective, displacing 37 million people is equivalent to

removing nearly all the residents of the state of California or all

the people in Texas and Virginia combined. The figure is almost as

large as the population of Canada. In historical terms, 37 million

displaced is more than those displaced by any other war or disaster

since at least the start of the twentieth century with the sole

exception of World War II (see Table 2).

The United States’ post-9/11 wars have contributed significantly to

the dramatic increase in recent years in the number of people

displaced by war and violent conflict worldwide: Between 2010 and

2019, the total number of refugees and IDPs globally has nearly

doubled from 41 million to 79.5 million.

In the next section, this paper proceeds with an overview of our

methodology and approach to calculating wartime displacement. A

more detailed discussion is in the Appendix. We next provide an

overview of displacement in each war-affected country. We then

present the results of our calculations and discuss the limits of

quantitative measurement. We conclude by discussing the

significance of our findings to assessments of the post-9/11 wars,

to debates about the use of military force more broadly, and to

questions about who bears responsibility for repairing damage

suffered by the displaced.

...

Somalia (2002–present)

[Conflict in Somalia has been ongoing since the early 1990s, when

some 3 million were displaced and one quarter million died; the

roots of the violence date to at least the U.S.-Soviet Cold War

and involve longstanding competition over territory, regional

autonomy, and resources. In the 1990s, the U.S. military sent

25,000 troops as part of UN humanitarian operations. They left

after soldiers took heavy casualties during fighting in Mogadishu

in 1993. See, e.g., Global IDP Project, “Internally Displaced

Somalis,” 4–5, 11–13; Catherine Besteman, “The Costs of War in

Somalia,” Brown University, Costs of War Project, September 5,

2019; Anna Lindley and Anita Haslie, “Unlocking Protracted

Displacement: Somali Case Study,” Working Paper Series No. 79,

Oxford University, August 2011, 301,

https://www.rsc.ox.ac.uk/files/files-1/wp79-unlocking-protracted

displacement-somalia-2011.pdf.]

Displacement has shaped life in Somalia for decades. In 2004, the

Norwegian Refugee Council reported that “virtually all

[emphasis added] Somalis have been displaced by violence at least

once in their life.” The U.S. government has been involved in

fighting there since 2002, shortly after the George W. Bush

administration declared its “war on terrorism.” For most of the

last 19 years, U.S. forces have used military bases in Djibouti and

elsewhere in the region to carry out drone assassinations of

alleged militants. In 2006, the U.S. military and CIA backed an

Ethiopian-led invasion of Somalia to remove the Islamic Courts

Union (ICU) from power. U.S. and Ethiopian leaders claimed the ICU

was an Al Qaeda ally; ICU leaders denied the charge. The invasion

succeeded in further radicalizing the ICU’s armed wing, Al Shabaab,

which declared allegiance to Al Qaeda in 2012. A war between Al

Shabaab and a UN-recognized Somali government and its U.S. and

other foreign allies continues to this day. U.S. forces have

expanded their presence in Somalia in recent years: there are at

least five small U.S. military bases and at least one CIA base in

the country. The Donald Trump administration has dramatically

increased air strikes against Al Shabaab and an Islamic State

presence; civilian casualties have also increased, with an

estimated 15 killed in 2020 and scores killed since 2007.

Political instability and violent conflict have heightened and been

mutually reinforcing with humanitarian crises caused by drought,

flooding, attendant famine, and widespread poverty. By the end of

2010, amid a famine that would kill hundreds of thousands, almost

1.5 million people had been displaced due to conflict and violence.

In 2019 alone, there were almost 200,000 new cases of internal

displacement, mostly around Al Shabaab’s stronghold in southeast

Somalia. In total, by the end of 2019, approximately 4.2 million

Somalis had been displaced within the country (3.4 million) or

beyond its borders as refugees or asylum seekers (800,000). Most

refugees ended up in neighboring countries such as Kenya, Ethiopia,

and Yemen. Smaller numbers have reached Uganda, Djibouti, South

Africa, Germany, and Sweden. Thousands reached the United States

during each year of the George W. Bush and Obama administrations,

while less than 700 have arrived in the last three years of the

Trump administration.

...

Libya (2011–present)

Hundreds of thousands of Libyans have been displaced in the years

following the 2011 Arab Spring uprising against longtime ruler

Muammar Gaddafi and the U.S., U.K., French, and Qatari invasion

that subsequently helped overthrow his regime. Violence increased

following the outside military intervention, and the country

plunged into a civil war involving “myriads of militias” and a

growing Islamic State presence. The subtitle of an IDMC report

summarizes what ensued: “State Collapse Triggers Mass

Displacement.” In 2011, alone, around 150,000 fled the country,

mostly to Tunisia. Most returned to Libya within a matter of

months, but by 2015, there were a total of 500,000 IDPs across the

country. More than 8% of the population had been displaced

internally.

The war’s destabilization of Libya also significantly impacted

migration patterns in Africa’s Sahel region. Darker-skinned

immigrants from West African and Sub-Saharan African countries,

whom Gaddafi had welcomed as a labor force in Libya, experienced

increased violence, racism, and displacement following Gaddafi’s

downfall. Some Libyans attacked Black Africans and others who

supported Gaddafi or were perceived to have benefitted from his

rule, fueling displacement. Around 15,000, mostly sub-Saharan

migrant laborers, fled abroad in 2011. In subsequent years,

violence and instability in Libya has made the country a center of

human trafficking and the main point of departure for migrants

attempting to cross the Mediterranean Sea to Europe.

Violence and displacement decreased after 2016 but rebounded in

2019 after an intensification of the ongoing civil war between the

Libyan National Army and the UN backed Government of National

Accord. Both sides are backed by external powers, including Russia

and Turkey, respectively, in what has become a full-fledged proxy

war. In 2019, new internal displacement incidents tripled over the

prior year to 215,000. A total of around 451,000 were living as

IDPs by year’s end.

As of 2019, IDMC reports that 97% of Libyan IDPs were struggling to

cover basic expenses, 17% were food insecure (53% in the capital,

Tripoli), and 46% could not afford healthcare. Among working-age

IDPs, 29% reported that their incomes had decreased by up to 50%.

Despite some progress toward a ceasefire and peace, the situation

remains “extremely fragile.”

Displacement in the U.S. Post-9/11 Wars: 37 million

Based on the methodology discussed in detail in the Appendix, we

now present our total displacement calculations. ...

Our 37 million estimate is also conservative because it does not

include millions more who have been displaced during other

post-9/11 wars and conflicts where U.S. forces have been involved

in relatively limited but still substantial ways. The U.S.

government has employed combat troops, drone strikes and

surveillance, military training, arms sales, and other pro-

government aid in countries including Burkina Faso, Cameroon,

Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo,

Kenya, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia (related to

the war in Yemen), South Sudan, Tunisia, and Uganda.

In most of these countries, the U.S. military and allied European

forces have backed national governments’ counter-insurgency

campaigns and “counter-terrorism” operations against Islamist

militants and other insurgents. In Burkina Faso, for example, there

were more than half a million incidents of displacement in 2019; by

year’s end, around 560,000 Burkinabe were living as IDPs. In Mali,

208,000 were living as IDPs by the end of 2019 as a result of years

of violent conflict. Since 2001, U.S. combat troops have operated

in every single one of the ten countries now suffering from the

most severe internal displacement in the world, according to IDMC.

The Central African Republic joins Burkina Faso and Mali in the top

three. The rest of the top ten include Niger, Chad, Cameroon, the

Democratic Republic of the Congo, as well as Somalia, Syria, and

Yemen.

********************************************************************

Overhauling U.S. Foreign Policy: Bitter Fights Ahead

by William Minter and Imani Countess*

* Imani Countess is an Open Society Fellow focusing on economic inequality. William Minter is the editor of AfricaFocus Bulletin. This essay, which appeared first in Organizing Upgrade on September 22, builds on a multipart essay series entitled Beyond Eurocentrism and U.S. Exceptionalism.

Protest outside the U.S Embassy in Kenya, June 9, 2020. Photo: The Star, Kenya

The most consequential election year in most of our lifetimes has featured stark crises unspooling against a backdrop of vigorous activist mobilizations and simmering public outrage. While the first essential step for progressives is to prevent the reelection of President Trump, that will not be enough. We need fundamental change rather than a return to the status quo ante.

Climate change, public health, police violence, and the systemic racism manifest in all policy areas are on the November 3 ballot. On these issues and others there is already significant mobilization to hold an incoming Democratic administration accountable.

This will not be easy, especially when it comes to foreign policy. The Democratic Party platform says that “we cannot simply aspire to restore American leadership. We must reinvent it for a new era.” But it fails to question the legitimacy of American preeminence and exceptionalism—or, more broadly, the understanding of the world as an arena primarily for competition rather than collaboration.

Challenge Militarism

Despite rising criticism of wasted money and endless wars, in late July significant majorities in the U.S. Congress, including Democrats as well as Republicans, defeated an amendment to cut 10% from the $740.5 billion military budget. The vote was 324 to 93 in the House of Representatives and 77 to 23 in the Senate.

There are critiques across a wide political spectrum of the U.S. military posture, and widely shared uneasiness about endless wars. But there is still no strong antiwar movement with links to progressive movements focused on domestic policy. The default assumption in public debate is that U.S. wars were and still are aimed at protecting the security of the United States. Military spending to defend against “adversaries” takes priority over spending that would enable the United States to play its part in combating common global threats and investing in human security.

Foreign policy veterans of the Obama-Biden years vary significantly in their views. Some acknowledge that policy cannot just return to the status quo before Trump. Yet even those who are most critical of previous policy still speak of “rebuilding the city on a hill”—the United States as leader and shining example for the world. Few are willing to engage in fundamental questioning of the U.S. global role.

Andrew Bacevich, a longtime critic of militarism, and others at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft are bringing options for anti-militarist positions into the establishment debate. But more substantive change is only likely to happen with greater pressure from progressive voices that are now largely outside the foreign policy establishment.

To be effective, mobilization must be broad, extending beyond foreign policy–focused constituencies to engage large swathes of the U.S. public. This vast reach marked the movement against the Vietnam War and the solidarity movements with Southern Africa and Central America in the 1970s and 1980s. Those mobilizations, however, were largely driven by external events and nightly news coverage that made the U.S. role impossible to ignore.

Today, as our military engagements drag on with dwindling media attention, there are fewer dramatic headlines to propel global issues into mainstream media and political debate. This makes it difficult, though by no means impossible, to build wider consciousness of global issues.

Forge National-Global Connections

As progressives, we can educate ourselves now to advance a global perspective and help pave the way for lobbying campaigns by progressive organizations seeking to influence a new administration.

As a first step, activists and organizations working primarily on domestic issues and those working on global or foreign policy issues should build closer links of understanding between them, even as they recognize the need to work along parallel tracks. Examples include the recent article by Max Elbaum in Organizing Upgrade, the wide range of organizations involved in the National Priorities Project, and the inclusion of action against militarism among the key demands of the Poor People's Campaign.

We should focus on issues, not on personalities. Defeating Trump is a prerequisite for advancing a progressive agenda, but opportunities for influencing a future Biden administration will depend on the strength of movements that put forth compelling alternative visions on key issues.

We should reinforce the message from climate justice organizations, such as the Sunrise Movement and 350.org, that the Green New Deal must be global. Among the specific implications: multilateral and bilateral collaboration with China is imperative, while a strategic partnership with the oil-rich Gulf autocracies is obsolete.

The Covid-19 pandemic makes clear that action to protect the right to health must be global. Among the specific implications: the United States must not only support the World Health Organization, but must learn from countries as diverse as Cuba, Vietnam, New Zealand, and South Korea, to name only a few.

As indicated by actions around the world in solidarity with #BlackLivesMatter, progressive activists in the United States need to recognize that anti-Black racism is global and not confined to any one country. This racism shows itself in the treatment of Africans and Afro-descendants in a wide range of countries and is reflected in the position of the African continent in the global hierarchy.

Call Attention to Fundamental Parallels

Both domestic law enforcement and the conduct of foreign wars continue to reflect the history of conquest, slavery, and U.S. empire of earlier centuries. The continuing effects of the “original sin” of slavery are now widely recognized; the effects of our imperial past on indigenous populations and the world receive less attention. Both domestic and global inequalities of all kinds are rooted in the history of conquest and empire as well as of slavery.

Follow the money! In communities around the country, local authorities are being challenged to divest from over-policing and invest in community needs instead. The same scrutiny and demands should apply to the federal budget, redirecting resources away from the military and toward investment in global public goods that advance human security.

It is also essential to address tax injustice by applying higher rates to the ultra-rich and by pursuing the wealth hidden in offshore accounts by corporations and wealthy elites around the world.This loss of capital is particularly acute for African countries, where local elites are conniving with a global network of facilitators to loot the continent. Efforts to curb such looting, by locating and taxing hidden wealth, would free up funds to be invested in Africa's urgent needs. The Stop the Bleeding campaign of African civil society groups, coordinated by Tax Justice Network-Africa, is working toward this aim with support from the Global Alliance for Tax Justice.

Don't Go Along with Foreign Policy Taboos

We should not shy away from confronting tough political issues with alternative frameworks. An area of particular concern, given current political biases among Democratic as well as Republican establishments, is support for justice in Palestine and Israel through global solidarity, including Palestinian, Jewish and other activists in the United States. We also need to mobilize resistance to the bipartisan trend toward a new Cold War with China, and support partnership for justice based on reliable information rather than arrogant unilateral intervention in crises such as those in Venezuela and Ecuador.

Progressives should prioritize support for members of Congress willing to speak out against foreign policy taboos, such as those in “the squad,” the Congressional Black Caucus, and the Congressional Progressive Caucus.

Don't Be Afraid to Dream

To challenge a new Democratic administration and inspire progressive mobilization, we should advance not only practical policy goals but also new visions of mutual cooperation beyond those presently thinkable. One clear albeit difficult example is the case of Cuba, where U.S. policy has been paralyzed for decades by right-wing pressures.

A progressive agenda for U.S.-Cuban relations should begin with the reversal of new restrictive measures imposed by the Trump administration and progress toward full elimination of the trade embargo and travel restrictions that have defined U.S. policy for almost six decades.

A more ambitious goal would be to stress U.S. collaboration with Cuba in promoting global health, as happened in the case of Ebola in West Africa. The United States should be prepared to accept future Cuban offers of assistance with disaster relief and preparedness, an offer that the George W. Bush administration rejected in 2005 after Hurricane Katrina. Most visionary, but also beneficial to both countries, would be for the United States to ask Cuba for technical assistance in developing equitable public health policies in this country—and to pay generously for such assistance. That could promote mutual understanding as well as begin to pay for repairing the damage done over many decades of U.S. intervention in Cuba.

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication

providing reposted commentary and analysis on African issues, with

a particular focus on U.S. and international policies. AfricaFocus

Bulletin is edited by William Minter. For an archive of previous Bulletins,

see http://www.africafocus.org,

Current links to books on AfricaFocus go to the non-profit bookshop.org, which supports independent bookshores and also provides commissions to affiliates such as AfricaFocus.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please

write to this address to suggest material for inclusion. For more

information about reposted material, please contact directly the

original source mentioned. To subscribe to receive future bulletins by email,

click here.

|