|

Algeria

Angola

Benin

Botswana

Burkina Faso

Burundi

Cameroon

Cape Verde

Central Afr. Rep.

Chad

Comoros

Congo (Brazzaville)

Congo (Kinshasa)

Côte d'Ivoire

Djibouti

Egypt

Equatorial Guinea

Eritrea

Ethiopia

Gabon

Gambia

Ghana

Guinea

Guinea-Bissau

Kenya

Lesotho

Liberia

Libya

Madagascar

Malawi

Mali

Mauritania

Mauritius

Morocco

Mozambique

Namibia

Niger

Nigeria

Rwanda

São Tomé

Senegal

Seychelles

Sierra Leone

Somalia

South Africa

South Sudan

Sudan

Swaziland

Tanzania

Togo

Tunisia

Uganda

Western Sahara

Zambia

Zimbabwe

|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

USA/Global: National and Global Inequalities Are Intertwined

AfricaFocus Bulletin

February 24, 2020 (2020-02-24)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

The recession that began in 2008 brought new life to the public debate on class and racial inequality in the United States. The #OccupyWallStreet demonstrations in 2011 may have left no institutional legacy, but they shined a spotlight on a yawning wealth gap and the role of the “one percent.” #BlackLivesMatter and related movements challenged complacency on entrenched racism … Public awareness of inequality, like awareness of climate change, was rising even before President Trump took office. But his administration’s sharp turn toward denial and regression on both issues has spurred active opposition and cut into the complacency of conventional Democratic Party politics.

However, while most people understand the climate issue as global, as argued in a previous AfricaFocus essay in January, the U.S. debate on national inequality between rich and poor households has not yet broadened into a conversation about global inequality between rich and poor countries. This theme remains muted at best, even among progressive activists.

This next essay in this series on shifting the paradigm from foreign policy to global policy. addresses this often invisible nexus of how money flows to the ultra-rich both within and across borders, how it is linked to deep structural realities of national and global history, and how finding the resources to address acute public needs requires not only higher tax rates but enforcing transparency about hidden wealth worldwide.

The two previous essays, both published on January 27, were Beyond Eurocentrism and U.S. Exceptionalism and Green New Deal Can and Must Be Global.

Thanks to the Praxis Center for republishing the essay on the climate emergency in two parts, on February 4 and February 11.

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

National and Global Inequalities Are Intertwined

by William Minter and Imani Countess*

* William Minter is the editor of AfricaFocus Bulletin. Imani Countess is an Open Society Fellow focusing on economic inequality. This essay is the third in a multipart series beginning in January 2020. Thanks to Catherine Sunshine for editing the essays in this series.

The recession that began in 2008 brought new life to the public debate on class inequality in the United States. The #OccupyWallStreet demonstrations in 2011 may have left no institutional legacy, but they shined a spotlight on a yawning wealth gap and the role of the “one percent.”1 In 2020, these themes are being sounded in national media and even on the presidential debate stage.

At the same time, complacence about racial inequality is being challenged. Thanks to the activism of #BlackLivesMatter and other racial justice groups, there are perceptible shifts in public opinion, including among some whites and particularly among youth. The racial justice movement initially focused on police violence but rapidly extended its vision to fundamental issues of inequality and national identity. The impact on mainstream opinion was symbolized in 2019 by the 1619 Project, a New York Times Magazine feature reflecting on 400 years of the impact of slavery.

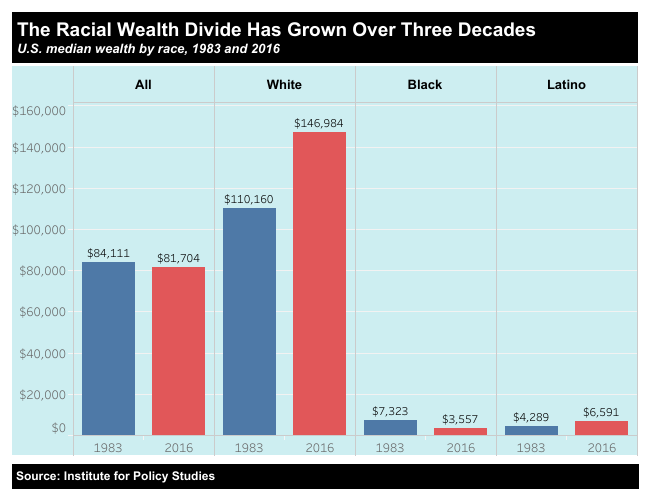

Gross economic inequality in the United States by class and race is not new, but it has increased rapidly in recent decades. Wealth inequality is far greater than income inequality, though both are on the rise. Economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman have compiled extensive data sets on wealth distribution since 1913. After wealth concentration peaked in 1929, the trend was toward greater equality until the late 1970s. Since then, though, inequality has increased steadily. Two factors among many are the declining strength of unions and tax policies that advantage the rich, enacted under both Republican and Democratic administrations.2

In 1979, in the United States, the top one-tenth of one percent owned 7% of the wealth; this tripled to 22% by 2012. The share of wealth held by the bottom half of the population is almost net zero, as debts balance out assets. So the losses have hit the top 50% to 90% of families. The effects on minority populations have been particularly extreme.

Public awareness of inequality, like awareness of climate change, was rising even before President Trump took office. But his administration’s sharp turn toward denial and regression on both issues has spurred active opposition and cut into the complacency of conventional Democratic Party politics.

However, while most people understand the climate issue as global, the U.S. debate on national inequality between rich and poor households has not yet broadened into a conversation about global inequality between rich and poor countries. This theme remains muted at best, even among progressive activists.

What would it take to start such a conversation? An understanding of history, for starters:

- Slavery and its lasting impact, so well documented in this 400th year anniversary, was not just a U.S. experience. It was shared by other countries in the Americas, based on a global capitalist system that included trade in slaves, sugar, and cotton. This trade was central to building the wealth of the United States and leading European countries.3

- The slave trade was followed in the late 19th century by European conquest of almost the entire African continent. Colonial economies were based on extraction of raw materials, shaping Africa’s subordinate role in the world economy. Moreover, the post-colonial independent states still reflect, in large part, the authoritarian political legacy of the colonial state. African elites stash much of their wealth outside the continent.4

- After independence, African countries remained part of a global hierarchy dominated both politically and economically by the European and North American countries. While China has a seat on the United Nations Security Council and Japan is part of the Group of 7, these forums exclude Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East. These regions are also underrepresented in the powerful World Bank and International Monetary Fund.

- The U.S.-led “Western liberal world order” that followed World War II had two faces. On one hand, it was built on a foundation of white supremacy and market capitalism, while on the other hand, it enshrined values of anti-colonialism and universal human rights, reflected in the expanding United Nations system. In recent years a rising tide of ethnonationalism and right-wing authoritarianism is undermining this postwar liberal order, despite pro-democracy protests in every region of the world.

Global Inequality: Wealth vs. Work

Beyond a grasp of history, U.S. activists need to understand how corruption, oligarchy, and inequality at the national level are tied to similar patterns around the world. Abundant evidence on rising global economic inequality is available from prominent academic sources.5 Nongovernmental organizations focused on development, such as Oxfam and ActionAid, highlight not only global poverty but also the extremes of wealth and the rapidly widening the gap between the ultra-rich and everyone else. Tax justice organizations in Europe, North America, and Africa show how tax resources needed for public investment are hidden in tax havens around the world – not just in small countries such as Luxembourg and Bermuda, but also in major financial centers such as London and New York. The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and related groups have done detailed reporting on secret transactions revealed in leaked documents such as the Panama Papers.

In January 2020, to coincide with the Davos World Economic Forum, Oxfam published its latest comparison. It observed that “In 2019, the world’s billionaires, only 2,153 people, had more wealth than 4.6 billion people. . . . The richest 22 men in the world own more wealth than all the women in Africa.” The previous year’s Oxfam report noted that a wealth tax of 0.5% on the richest 1% of the world’s population could “raise an estimated $418 billion a year – enough to educate every child not in school and provide healthcare that would prevent 3 million deaths.”

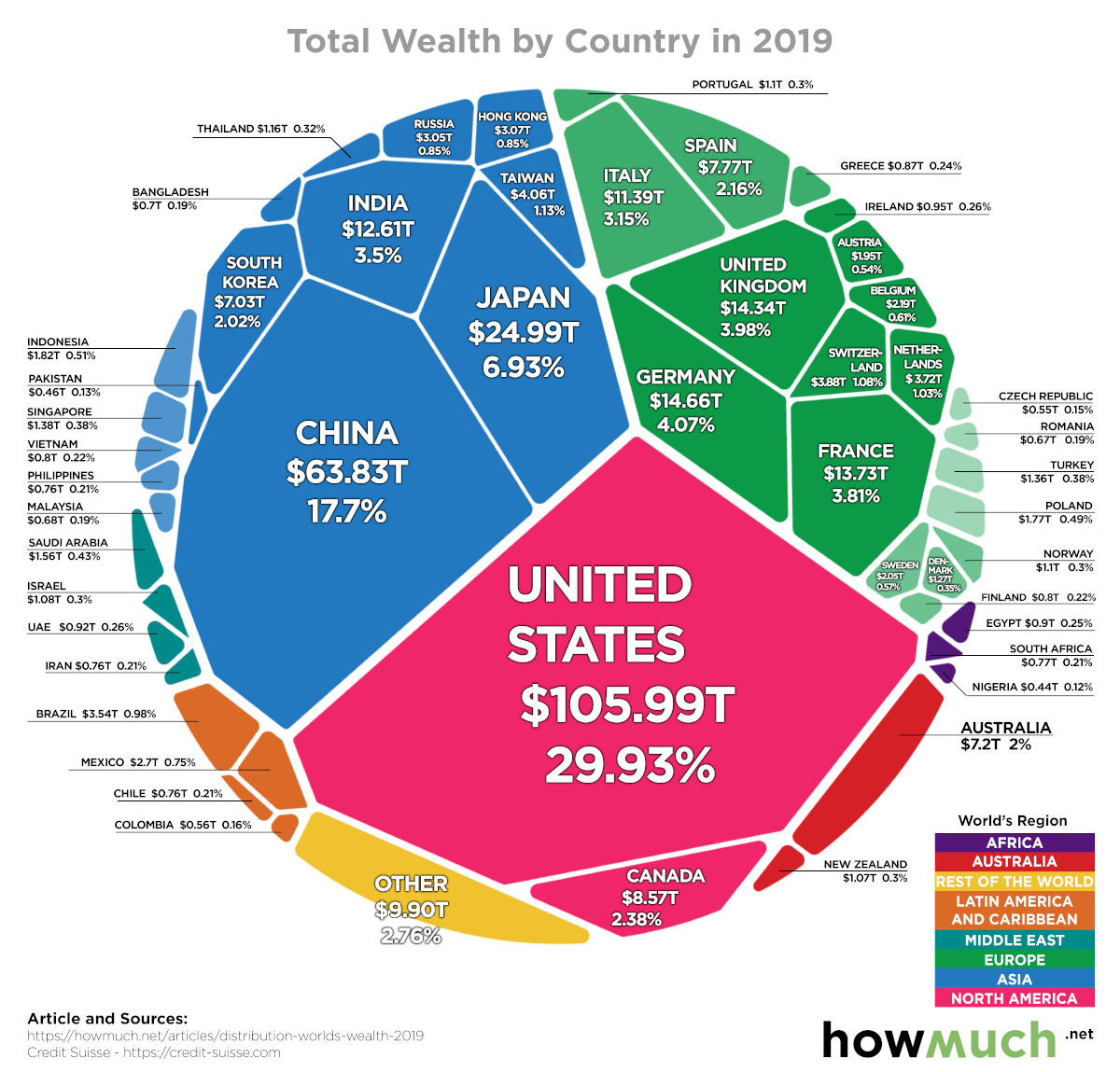

Compared to income, the distribution of wealth by country and region is far more unequal. In 2019, the median wealth per adult in Canada and the United States amounted to $69,162, almost ten times the global median of $7,087, according to Credit Suisse. For the African continent, including North Africa, median wealth per adult was only $1,219. Thus the inequalities of history continue to affect the resources available to countries today.

Gender and Work

At every level of the global hierarchy, wealth inequalities intersect with inequalities based on race, ethnicity, and gender. Those who are rich can accumulate even more wealth over their lifetimes or over generations. Those who depend primarily on income earned from work struggle to stay afloat and are constantly vulnerable to losing their jobs.

According to Oxfam, "At the top of the global economy a small elite are unimaginably rich. Their wealth grows exponentially over time, with little effort, and regardless of whether they add value to society. Meanwhile, at the bottom of the economy, women and girls, especially women and girls living in poverty and from marginalized groups, are putting in 12.5 billion hours every day of care work for free, and countless more for poverty wages. Their work is essential to our communities. It underpins thriving families and a healthy and productive workforce."

Oxfam calculates the monetary value of women’s unpaid care work globally as at least $10.8 trillion annually – three times the size of the world’s tech industry. Those laboring at low-paid jobs in health, education, and other essential sectors are also disproportionately women. Changing that reality requires public investment to provide public goods such as health, elder care, and child care, and ensuring that decent jobs with adequate pay are available to all. And checking the further growth of inequality, as technological change reshapes the global job market, requires government action to protect workers’ rights and provide economic opportunities. It also requires adequately financed universal social protection systems to protect both those who work and those unable to work for reasons of age, disability, or other limitations.

|

|

Domestic workers in South Africa, as in most countries around the world, are underpaid and are often not protected by legislation covering the formal work sector. Unions have campaigned to expand such protections, with some success. Credits: amandla.mobi and Labour Research Service.

Technological innovation – automation, the internet, smartphones, and more – continues to accelerate. The impact on the workforce, in terms of who reaps the benefits and who is further disadvantaged, is highly unequal. The gig economy, subcontracting, and remote access to work over online platforms open up doors for some. Meanwhile, formal work protected by strong unions and government regulation is everywhere in decline. That is why those who study the “future of work” stress the urgency of collective action. The Global Commission on the Future of Work, for example, lays out ten principles that should be adopted, including a universal guarantee of basic workers’ rights and social protection from birth to old age. Fulfilling these principles, however, requires both political will and financial resources.

Where’s the Money?

Almost 10% of the world’s wealth is held offshore, where it is shielded from the tax authorities of rich and poor countries alike. “Offshore,” however, is not a physical location but rather a fiction of legal paperwork. Ultra-rich individuals, aided by bankers, lawyers, and other financial agents, hide their money in a web of shell companies, while multinational corporations mask profits through accounting sleight-of-hand. Countries desperately need revenue to support economic and social development, but the information necessary to locate and tax the money is rarely accessible. The facts of who actually owns the wealth and where it is earned remain hidden, becoming visible only when revealed in court or outed by whistleblowers or investigative journalists.

Credit:

https://afrique.latribune.fr/

This is one of the key reasons why it is difficult for campaigns against global inequality to gain traction. Action must come from national governments, requiring political pressure focused on a single country. But the targets are elusive and their money easily takes flight across borders.

The latest and most sensational case is #LuandaLeaks, from the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) responsible for the #PanamaPapers and other previous exposés.

Africa’s richest woman, Isabel dos Santos, daughter of the man who served as president of Angola for 38 years, used her family connections to siphon off wealth into a network of more than 400 companies in 41 countries. The story is told in detail on the ICIJ website and in other press reports. The ICIJ documents how this fortune was built with the collaboration of leading Western firms, who helped dos Santos move money, set up companies, and avoid taxes. They include two of the four major global accounting firms, PwC and KPMG, as well as the Boston Consulting Group, one of the three top global management consulting firms. Although dos Santos faces confiscation of some of her properties following the scandal, there is no sign that her global enablers will suffer any serious penalty.6

Recovering the Money for Public Goods

Governments in many countries are starved for resources to meet public needs, such as health, education, and other essential investments. But the need, and the hemorrhage of resources, is most blatant on the African continent. Estimates of illegal transactions in Africa show a loss of at least $50 billion to $80 billion in wealth every year, a figure that would be incalculably more if transfers made legal by loopholes and unfair treaties were included. Some flows are only seen as “legal” because the laws are written and interpreted by those who profit from the system. Nevertheless, even the outflow of clearly illegal funds is far greater than the estimated $40 billion a year that Africa receives in official development assistance.

Despite corruption at the top in many African countries, networks of civil society activists and honest public servants are organizing to expose and curb illicit financial flows – money that is illegally earned, transferred, or used. They are aware that the culprits are not only corrupt national leaders but a global system, requiring a global response. In 2015, a coalition of six Pan African activist networks launched #StoptheBleeding Africa in Nairobi to mobilize global support to end illicit financial flows.

African countries are taking action on their own to tighten controls on revenue losses. And dedicated civil servants in many African governments are coordinating these efforts through the African Union and the United Nations Economic Commission on Africa.7 But their leverage is limited without support from the rich countries that shape global rules and host much of the stolen wealth. In the 1960s wave of African independence struggles, and again during the 1980s global anti-apartheid movement, African initiative spurred global solidarity, notably among African Americans as well as others in the United States. But illicit financial flows, despite their massive impact, lack the clear visibility of those earlier struggles.

Still, the issue is rising, both in the U.S. and globally, as demands for new public investments run up against the obstacle of where to find the money to pay for them. The logical answer, already surfacing prominently in the U.S. presidential campaign, is fairer taxation, targeting multinational corporations and the extremely rich.8 This implies reversing the trend to minimize taxes on the rich which has accelerated since the 1980s. According to Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, the average tax rate on income from capital dropped from a peak of 46% in the early 1950s to under 30% in 2018. Reformers are demanding a return to higher top rates for both individual and corporate taxes, as well as demanding new taxes, such as wealth taxes on the ultra-rich and the RobinHood tax on stock transactions.9

In addition to political will, two steps are essential to ensure that hidden wealth, estimated at anywhere from $9 trillion to over $21 trillion, is available for taxation. First, to ensure that multinational corporations don’t conceal their profits by transferring them to low-tax or no-tax jurisdictions, there must be a legal requirement for public country-by-country reporting. This needs to include transparency on where money is earned, where workers are employed, details of taxes paid, and other key data, in public financial statements reported to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Second, all corporations and other business entities must be required to make public reports on who really owns and controls them. The United States is one of the easiest places in the world to form anonymous shell companies. A requirement to report beneficial ownership would make it possible for tax authorities, lawmakers, and the public to “follow the money” and conduct informed debate about fair rates of taxation.

Steps toward these goals are gaining bipartisan support in the U.S. Congress, as well as among many investors and business leaders. According to an April 2019 report from the U.S.-based Financial Accountability and Corporate Transparency (FACT) Coalition, the trend is in the right direction. “The evidence suggests we are quickly reaching a turning point,” said Christian Freymeyer, author of the report. “Investors see the value, policymakers see the benefits, and businesses see the inevitability of greater transparency. It’s only a matter of time before tax transparency is accepted and expected of financial disclosure.”

Freymeyer’s analysis may err on the side of optimism, given the continued opposition from those with vested interests in tax avoidance. But the argument is gaining ground. Even limited actions will assist U.S. taxpayers and those in other countries seeking to tax resources extracted from their economies. Significant action will depend above all on the outcome of the 2020 elections. But it will also depend on continuing pressure from social movements, insisting that the U.S. government take responsibility for addressing inequalities not only in income and wealth but in access to fundamental human rights.

In the fourth installment in this series, we will look at how social movements are changing political awareness in the United States about the urgency of universal economic and social rights, including the right to health and the right to a living wage and decent work, and how these parallel worldwide demands for these rights.

Notes

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication

providing reposted commentary and analysis on African issues, with

a particular focus on U.S. and international policies. AfricaFocus

Bulletin is edited by William Minter.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please

write to this address to suggest material for inclusion. For more

information about reposted material, please contact directly the

original source mentioned. For a full archive and other resources,

see http://www.africafocus.org

|