|

Algeria

Angola

Benin

Botswana

Burkina Faso

Burundi

Cameroon

Cape Verde

Central Afr. Rep.

Chad

Comoros

Congo (Brazzaville)

Congo (Kinshasa)

Côte d'Ivoire

Djibouti

Egypt

Equatorial Guinea

Eritrea

Ethiopia

Gabon

Gambia

Ghana

Guinea

Guinea-Bissau

Kenya

Lesotho

Liberia

Libya

Madagascar

Malawi

Mali

Mauritania

Mauritius

Morocco

Mozambique

Namibia

Niger

Nigeria

Rwanda

São Tomé

Senegal

Seychelles

Sierra Leone

Somalia

South Africa

South Sudan

Sudan

Swaziland

Tanzania

Togo

Tunisia

Uganda

Western Sahara

Zambia

Zimbabwe

|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

USA/Global: Beyond Eurocentrism and U.S. Exceptionalism

AfricaFocus Bulletin

January 27, 2020 (2020-01-27)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor´s Note

Since his election, Trump’s erratic policies have aligned the

United States with right-wing authoritarians across the globe, fed

global currents of xenophobia and racism, and dismayed traditional

allies. In 2019, nevertheless, foreign policy was a low priority in

the 2020 presidential campaign. In January 2020, the

administration´s killing of Iranian leader Qassem Soleimani evoked

widespread opposition amid fears of a wider war in the Middle East.

Even so, evidence of new thinking on the U.S. role in the world,

beyond opposition to Trump, remained sparse. Former Vice

President Joe Biden called for a return to American leadership as

it existed in an era “before Trump,” and harked back to the

“liberal” U.S.-led global order after World War II, which centered

the alliance of Western democracies in the North Atlantic and the

Cold War against the Soviet Union. But even Bernie Sanders and

Elizabeth Warren only took tentative steps towards laying out an

alternative foreign policy vision.

This AfricaFocus Bulletin is the first in a series exploring the potential for a paradigm shift from foreign policy to global policy in debate about the United States role in the world. Unlike most AfricaFocus Bulletins, the essays are not reposted material but original reflections in this U.S. presidential election year, co-authored by your editor and by experienced activist and policy analyst Imani Countess. Many AfricaFocus readers will know Imani from her previous work, but others will not, so a brief introduction is in order.

Imani Countess is currently an Open Society Fellow working on economic inequality, and particularly the impact of illicit financial flows on Africa and how to mobilize pressure to curb U.S. involvement as a major player in this global unjust system. I first worked closely with Imani in 1991-1997 when she was executive director of the Washington Office on Africa and the Africa Policy Information Center and I was a part-time consultant working on policy analysis, writing, and electronic communication tools for the twin organizations. Since then, we have kept in touch and often collaborated on research and writing projects, as she has played key roles at the African Development Foundation, the American Friends Service Committee, TransAfrica Forum, and the Solidarity Center. She also currently serves as vice chair of the board of directors of ActionAid USA.

Our goal in this writing project is not to lay out a comprehensive vision of U.S. foreign policy or of U.S. policy toward Africa. It is rather to suggest that the time is ripe for re-visioning how we think about the U.S. role in the world, and that such rethinking is essential for any fundamental changes in policy towards Africa or towards any of the global issues on which Africa both suffers greatest vulnerability and has significant potential for leading global rethinking about solutions.

Special thanks to Catherine Sunshine for her indispensable role in editing these essays. And thanks to the friends and colleagues who have provided helpful feedback as we have tried to put these ideas into words. To date these include Jim Cason, John Cavanagh, Gail Hovey, John Feffer, Zeb Larson, Prexy Nesbitt, Anita Plummer, Elizabeth Schmidt, and Brandon Wu.

And thanks to other readers in advance for passing this on to friends and colleagues not likely to be subscribers to AfricaFocus, as well as for your own feedback on how to make such a shift in our collective discussions.

The second part of the series, on the climate emergency, is

also being published today and is available at http://www.africafocus.org/docs20/clim2001.php.

|

Beyond Eurocentrism and U.S. Exceptionalism:

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization was created in 1949 by the United States, Canada, and 7 Western European nations to provide collective security against the Soviet Union. Additional members brought the membership up to 27 by 2017. Credit:

http://history.com.

|

Starting Points for a Paradigm Shift from Foreign Policy to Global Policy

by William Minter and Imani Countess*

* William Minter is the editor of AfricaFocus Bulletin. Imani

Countess is an Open Society Fellow focusing on economic inequality.

This essay is the first in a multipart series beginning in January 2020. Thanks to Catherine Sunshine for her editing of the essays in this series.

Since his election, Trump’s erratic policies have aligned the

United States with right-wing authoritarians across the globe, fed

global currents of xenophobia and racism, and dismayed traditional

allies. In 2019, nevertheless, foreign policy was a low priority in

the 2020 presidential campaign. In January 2020, the

administration´s killing of Iranian leader Qassem Soleimani evoked

widespread opposition amid fears of a wider war in the Middle East.

Even so, evidence of new thinking on the U.S. role in the world,

beyond opposition to Trump, remained sparse. Former Vice

President Joe Biden called for a return to American leadership as

it existed in an era “before Trump,” and harked back to the

“liberal” U.S.-led global order after World War II, which centered

the alliance of Western democracies in the North Atlantic and the

Cold War against the Soviet Union. But even Bernie Sanders and

Elizabeth Warren only took tentative steps towards laying out an

alternative foreign policy vision.1

Yet rising attention to the climate crisis, immigration, and

economic inequality, while not categorized under “foreign policy,”

hints at a broader scope more attuned to a global vision. History,

too, offers other options. Instead of only the North Atlantic, one

can highlight the worldwide anti-fascist coalition in World War II,

the United Nations, international declarations on human rights, and

the history of anti-colonial and anti-racist struggles around the

world. In the era of African and Asian freedom struggles, Black

American activists, but also many others, made connections between

civil rights movements at home and their counterparts on other

continents. This reached a height during the international anti-apartheid movement in particular. Activists today are beginning to

make similar connections through their engagement in common

struggles.

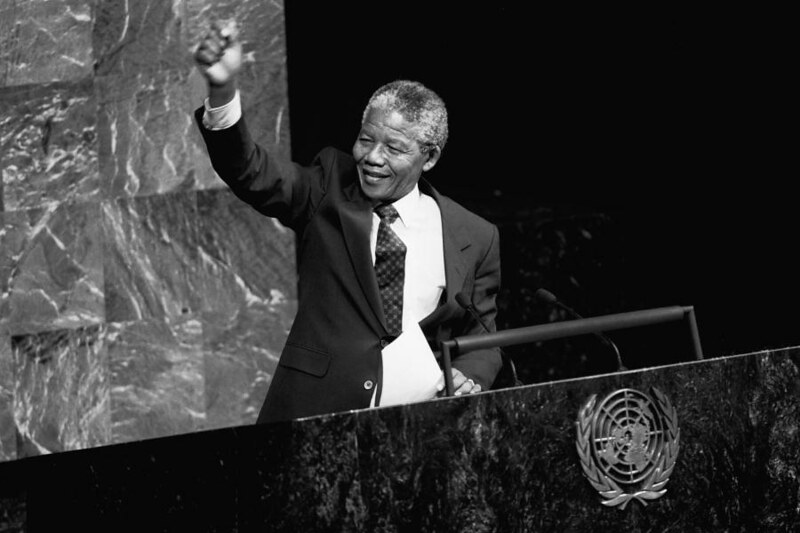

Nelson Mandela, Deputy President of the African National Congress of South Africa, addresses the Special Committee Against Apartheid in the General Assembly Hall. 22/Jun/1990. UN Photo/P Sudhakaran.

|

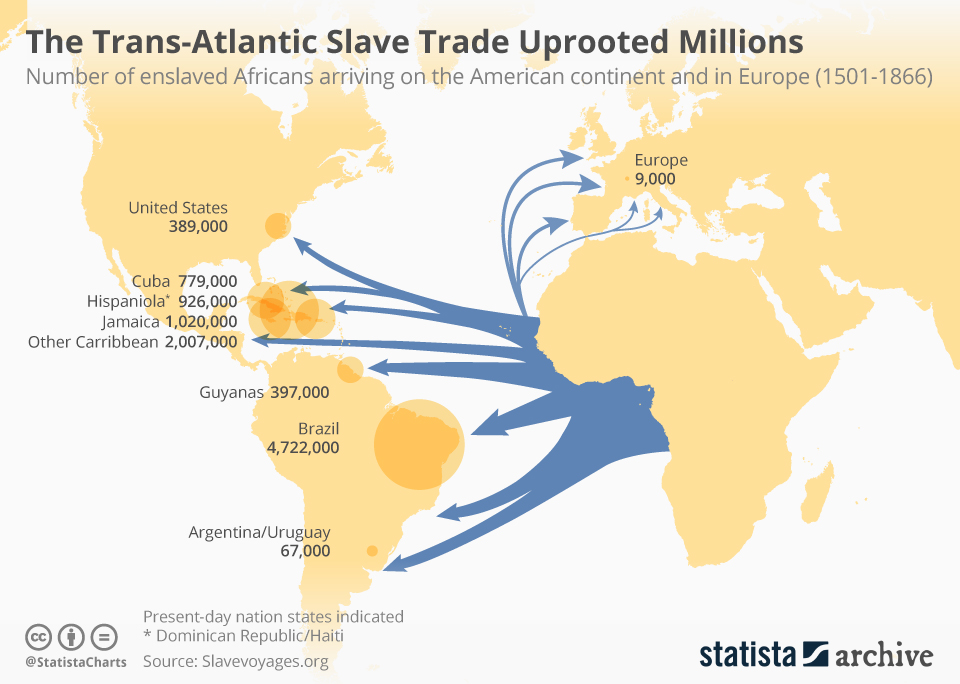

In exploring the options for new perspectives on national issues,

activists and many other Americans are increasingly turning to a

more critical examination of our history. Understanding the

persistent legacy of slavery and colonial conquest is central to

thinking about how to address contemporary domestic issues,

including but not limited to racial justice issues.2 A similar expansion of

our time horizon, looking at how the past influences the present,

is necessary for examining the causes of and solutions for today’s

global issues. This extends to the climate crisis, which is the

result of more than two centuries of fossil-fuel-powered

industrialization. It also applies to migration and economic

inequality, which have been shaped by more than five centuries of

conquest and colonialism by Europe and European settlers on other

continents.

The two driving forces that shape U.S. foreign policy, eurocentrism

and U.S. exceptionalism, are deeply rooted in U.S. history. The

country began as a white settler state whose identity was formed by

conquest of a continent and whose economy was built on slavery and

appropriated land. Elite assumptions about a unique American

destiny of unrivaled global leadership were solidified with the

post–World War II global order. In recent years, many have

criticized the current conventional wisdom, particularly its bias

toward militarism, and offered new options for foreign policy.3 But shifting

the dominant framework is likely to require more than debate

focused on foreign policy alone.

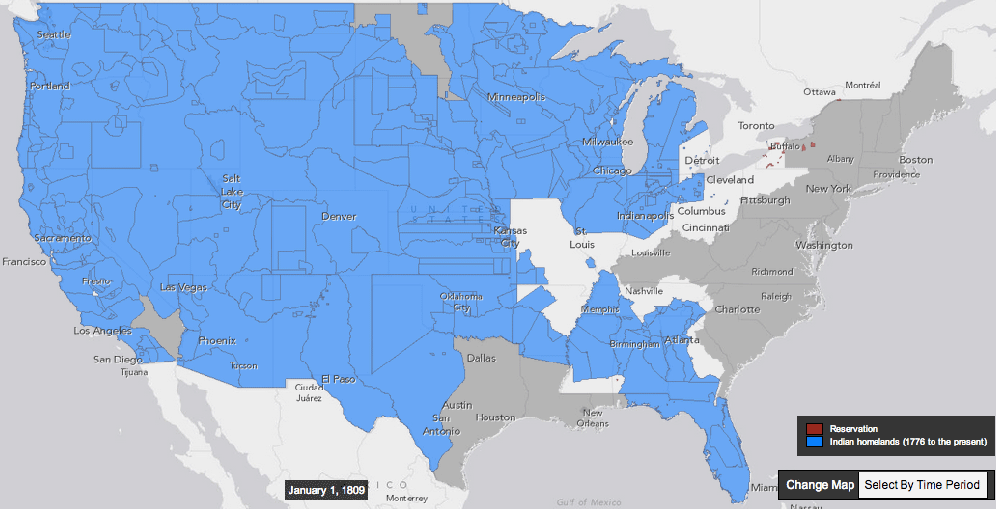

Interactive Time-Lapse Map Shows How the U.S. Took More Than 1.5 Billion Acres From Native Americans since 1776. Image shows map for 1809. For interactive map go to Slate.

|

|

In 2020 and beyond, growing domestic social justice movements could provide a different starting point for shaping U.S. relations with the rest of the world. The global issues that are simultaneously domestic issues, we contend, must provide the overarching context for “foreign policy” toward specific regions and countries.

In conventional wisdom, foreign policy focuses on geopolitics, economic competition, and military might, with a nod to diplomacy as well. All other issues, from climate change to human rights, migration, development, and economic inequality, are viewed as optional add-ons. A progressive alternative would give the highest long-term priority to these global issues, without ignoring the need to resolve immediate conflicts and manage state-to-state relationships with other countries. A “whole-of-government” approach, which has been most often applied to the national security sector, must put domestic and foreign policy within the same broader framework, one that prioritizes human security and human development at both national and global levels. Within such a perspective, foreign policy is not so much its own domain with separate rules, but rather a different arena in which the same issues must be addressed.

If one assumes a strict dichotomy of domestic policy versus foreign policy, it is natural that domestic policy will take priority in the eyes of most voters and politicians. Increasingly, however, almost all critical issues have domestic and international components and consequences that are closely intertwined. Climate change, to take just one example, is driven by emissions in the United States and multiple countries that rely on fossil fuels. It spawns lethal hurricanes in Texas and Florida and cyclones in Mozambique, wildfires in Australia and California. Nature does not respect national boundaries, and solutions must be implemented at all levels, from local to national and global. By taking our shared dilemmas into account, the United States can be better prepared to enter more productively into a truly reciprocal debate with other nations.

Port Arthur, Texas underwater. Hurricane Harvey, 2017. Credit: SC National Guard / Flickr.

|

Cyclone damage in Buzi, Mozambique. Cyclone Idai, 2019. Credit: Mozambique National Institute for Disaster Management.

|

While the climate crisis is perhaps the clearest example, other issues are also closely linked across borders, blurring the distinction between domestic and foreign. Migration, a hot-button issue in many countries, has shared causes, including global inequality, wars and human rights abuses, and climate emergencies. The right-wing drive toward authoritarianism and unfettered corruption relies on divisive racial and ethnic appeals that have taken root in multiple countries. And secret financial flows across borders concentrate wealth in the hands of the super-rich, who use the proceeds to manipulate political systems in all parts of the world.

What do Democratic candidates say?

All of the leading 2020 Democratic presidential candidates understand that Trump’s addictions to authoritarianism, racial and ethnic hatred, and the pursuit of wealth drive both his domestic and foreign policies. In this sense, the candidates do recognize the interconnections between domestic and global concerns. But a review of their foreign policy statements to date also shows significant differences in the ways they think about these issues.

Vice President Joe Biden, for example, calls for renewed American leadership and a return to pre-Trump normality, building on conventional foreign policy themes:

"Today, Joe Biden laid out his foreign policy vision for America to restore dignified leadership at home and respected leadership on the world stage. Arguing that our policies at home and abroad are deeply connected, Joe Biden announced that, as president, he will advance the security, prosperity, and values of the United States by taking immediate steps to renew our own democracy and alliances, protect our economic future, and once more place America at the head of the table, leading the world to address the most urgent global challenges."4

He then lays out a long list of goals, but provides no vision of a common global effort in which the United States is a participant rather than a leader. There is neither a critique of past policies nor an analysis of how today’s challenges differ from those of the past. In the summary on the Biden website, NATO is mentioned twice, and the United Nations or sustainable development not at all. Africa is cited only in the context of “integrating our friends in Latin America and Africa” into partnerships first defined by the North Atlantic partners.

Mayor Pete Buttigieg ambitiously titled his June 2019 foreign policy speech “America and the World in 2054: Reimagining National Security for a New Era.” And the speech did include climate change and paragraphs on Latin America and Africa. Like Biden, Buttigieg called for American leadership based on American values. In addition, he advanced specific proposals on several topics. But there was no mention of the United Nations or of global action to address poverty and inequality, or of international collaboration other than rejoining the Paris climate accord.

As they do on domestic issues, both Senator Elizabeth Warren and Senator Bernie Sanders offer substantive new ideas on foreign policy, although their foreign policy visions are still incomplete. And the two candidates also contrast in similar ways on foreign as well as domestic policy. Sanders offers a more comprehensive and critical vision but lacks detail on alternatives. Warren has more detailed plans, but she has not yet addressed some of the critiques leveled by Sanders at conventional policy in the period since World War II.

Both Warren and Sanders share the critique of Trump’s foreign policy advanced by other candidates. But they also give particular attention to the issues of economic inequality at a global level as well as domestically. While neither has advanced a systematic package of measures to address global inequality and sustainable development in order to narrow the wealth and income gaps between countries, Warren has incorporated key components of such a package into her plans under the rubric of economic patriotism.

The main pillar of that agenda is to protect and create American jobs. But in a supplementary plan for trade, Warren includes several provisions for using trade pacts to reinforce global standards, such as core labor rights and other internationally recognized human rights. She also proposes measures to address tax evasion and avoidance. In contrast to Biden’s perspective, Warren’s critique of previous U.S. foreign policy does not begin with Trump. In a speech at American University in November 2018, she described the postwar order as “not perfect.” But, she added,

"[B]eginning in the 1980s, Washington’s focus shifted from policies that benefit everyone to policies that benefit a handful of elites, both here at home and around the world. Mistakes piled on mistakes. Reckless, endless wars in the Middle East. Trade deals rammed through with callous disregard for our working people. Extraordinary expansion of risk in the global financial system."

Warren went on, in this speech and in a contemporaneous article in Foreign Affairs, to lay out an agenda for “making globalization work” and “ending endless war.” She also called for the United States to “work closely with allies to require transparency about the movement of assets across borders”—an issue that must be addressed to implement her well-publicized wealth tax of 2% on those with fortunes over $50 million. In December 2019, Warren launched her plan to address money laundering and related international corruption issues.

Sanders, for his part, stands out for his strong record on foreign policy since the 2016 election, including leadership in the fight to cut off U.S. support for the Saudi war in Yemen.5 In September 2017 he spelled out his foreign policy vision in a speech at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, where Winston Churchill gave his famous “Iron Curtain” speech in 1946. Sanders linked domestic and global threats to democracy, warned about the limits and dangers of the use of military power, and highlighted key global issues, including climate change and economic inequality. And he stressed the importance of the United Nations, recalling Eleanor Roosevelt’s reference to the organization as “our greatest hope for peace.”

Among the candidates, Sanders has been alone in radically challenging American exceptionalism. In his 2017 speech, he hailed the reconstruction of Western Europe with the Marshall Plan and the fact that “there has not been a major European war since World War II.” But he also recalled the history of “American intervention and the use of American military power ... which has caused incalculable harm.” He cited the Vietnam War along with U.S. interventions in Iran, Chile, and Iraq, and he castigated the counterproductive strategies of the global “war on terror.” He concluded his speech with a call for “partnerships not just between governments but between peoples.”

In the fall of 2018, Sanders further elaborated his vision in a speech in Washington and an article in The Guardian:

"On one hand, we see a growing worldwide movement toward authoritarianism, oligarchy, and kleptocracy. On the other side, we see a movement toward strengthening democracy, egalitarianism, and economic, social, racial, and environmental justice."

The grand vision is inspiring. But Sanders is still silent on what forces might come together to form what he calls a “progressive international.” As John Feffer points out in a commentary in Foreign Policy in Focus, “Sanders has a Eurocentric bias.” Feffer notes that Sanders’s speech in Fulton didn’t mention Africa and hardly touched on Latin America or Asia. The principal partner in Sanders’s progressive alliance is Yanis Varoufakis, the former Greek finance minister, who commented approvingly on Sanders’s Guardian article and is engaged in building a progressive coalition in Europe.

Whether simply through the rejection of Trump or through the more developed insights offered by Warren and Sanders, all the Democratic candidates point in some way to the interconnection of domestic policy and foreign policy. Given the priorities of a presidential campaign, however, formulating and articulating a full, long-term vision is unlikely to be high on their agendas. Nor is it in any way a simple project to come up with a vision and a set of policies that are both persuasive and attentive to the complex and diverse realities of different policy arenas.

The Road Ahead

It’s worth beginning to explore how a change in priorities on global issues might have implications for the conventional foreign policy framework based on geopolitics. This is relevant not only for the 2020 campaign, but for the development of social movements that can foster a richer conversation going beyond the conventional wisdom that currently prevails in political debate and among the foreign policy elite.

The following essays in this series focus first on the climate crisis and then on global economic inequalities, universal political and economic rights, migration, violence and security, and gender inequalities. A final section considers how national history and national identity shape and define the United States’ global role. We do not attempt the impossible task of providing a comprehensive analysis, but simply highlight some starting points for consideration within each issue cluster. Our approach does not center the big-power politics; instead we give more attention to the roles of multinational institutions, global civil society, and international social movements. We particularly highlight the centrality of the African continent to many of these debates. Not only is that our own background, but the position of Africa in the global debate, diminished by bias and marginalization, closely parallels the treatment of African American experiences in U.S. policy more generally—another pivotal domestic-foreign link.

In each case, we begin with recent shifts in the debate on national issues, shifts that have been fueled by progressive activist movements and have made their way into the Democratic primary debates. We lay out possible implications for foreign policy if similar changes were to be explored at the global level. And we contend that finding a new collaborative role for the United States on the world stage will require thinking that challenges conventional wisdom about our nation’s history and national identity.

We begin, in the next essay in this series, with the climate crisis, where there has already been significant recognition of the intrinsic global connection.

Notes

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication

providing reposted commentary and analysis on African issues, with

a particular focus on U.S. and international policies. AfricaFocus

Bulletin is edited by William Minter.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please

write to this address to suggest material for inclusion. For more

information about reposted material, please contact directly the

original source mentioned. For a full archive and other resources,

see http://www.africafocus.org

|