|

Algeria

Angola

Benin

Botswana

Burkina Faso

Burundi

Cameroon

Cape Verde

Central Afr. Rep.

Chad

Comoros

Congo (Brazzaville)

Congo (Kinshasa)

Côte d'Ivoire

Djibouti

Egypt

Equatorial Guinea

Eritrea

Ethiopia

Gabon

Gambia

Ghana

Guinea

Guinea-Bissau

Kenya

Lesotho

Liberia

Libya

Madagascar

Malawi

Mali

Mauritania

Mauritius

Morocco

Mozambique

Namibia

Niger

Nigeria

Rwanda

São Tomé

Senegal

Seychelles

Sierra Leone

Somalia

South Africa

South Sudan

Sudan

Swaziland

Tanzania

Togo

Tunisia

Uganda

Western Sahara

Zambia

Zimbabwe

|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

USA/Global: Divest from Violent Policing and Endless Wars, Part One

AfricaFocus Bulletin

August 24, 2020 (2020-08-24)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

The notion of policing as a war, in which more lethal force will lead to more security, is not a recent development, but is deeply rooted in U.S. history. The police and the military share the country’s legacy of white supremacy and violence against racial others, which has also given rise to mob and individual violence by white civilians. Both domestic law enforcement and the conduct of foreign wars continue to reflect the history of conquest, slavery, and U.S. empire of earlier centuries.

In previous essays in this series, we have argued that significant shifts in views on the home front are opening opportunities for similar changes in policy paradigms at the global level. Such is the case for action on the climate crisis, structural racism and class inequality, and economic rights such as the right to health and the right to a living wage. These trends were already underway early in the year, when we began this series by comparing the foreign policy platforms of the Democratic presidential candidates at the time. Since then, first the Covid-19 pandemic and then the nation-wide uprising against police violence and racism following the murder of George Floyd have accelerated the drive to change the narratives about the need for fundamental change.

In the two AfricaFocus Bulletins sent out today, we explore the

potential and the limitations on making similar links between the

domestic movement against violent policing and the need to make

fundamental changes in the global role of the U.S. military in

escalating violence rather than providing security.

This Bulletin, available at http://www.africafocus.org/docs20/viol2008-1.php, focuses on the profound impact of the Black Lives Matter movement from its origin as a hashtag in 2013. In a second Bulletin, also sent out today and available at http://www.africafocus.org/docs20/viol2008-2.php, we turn our attention to the deadly feedback loop between policing and empire in U.S. history and to the current status quo of the global U.S. military apparatus.

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins in this series, visit http://www.africafocus.org/usa-2020.php.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Making Herstory: Celebrating the Power of Southern African Women

Shared Interest Virtual Fundraising Gala, September 9, 2020, 7 pm EST

As many AfricaFocus readers are aware, Shared Interest, founded in 1994, focuses on addressing structural inequalities through providing loan guarantees for grassroots development groups, farmers, and small businesses in South Africa and other Southern African countries. Its annual fundraising gala this year will be virtual, particularly celebrating Southern African women. One of the honorees this year is 82-year-old Sophia Williams-de Bruyn, one of the leaders of the South African Women´s March in 1956.

Gala and dance party free on-line – registration required, donations requested but not required.

For more information and to register: https://www.sharedinterest.org/26thanniversarygala

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

Divest from Violent Policing and Endless Wars: Invest Instead in a New Social Contract, Part One

by William Minter and Imani Countess*

* William Minter is the editor of AfricaFocus Bulletin. Imani Countess is an Open Society Fellow focusing on economic inequality. This essay is part of a series entitled “Beyond Eurocentrism and U.S. Exceptionalism: Starting Points for a Paradigm Shift from Foreign Policy to Global Policy,” which began in January 2020. Thanks to Catherine Sunshine for editing the essays in this series.

The Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd in May 2020 have been the largest wave of protests in American history, according to calculations by the New York Times. They have erupted across the country in red states and blue states, in big cities and suburbs and small towns. This uprising, sparked by racial disparity in police violence, is playing out against a national backdrop of striking racial inequality in Covid-19 illnesses and deaths. Multiple surveys have documented significant recent shifts in public opinion on race, including among many white Americans.1

Going beyond a long history of failed reform efforts will be difficult. But the debate has been intensified and deepened with calls for action at local, state, and federal levels to defund the police and invest in positive rather than punitive programs to ensure public safety. The Justice in Policing Act, passed in June by the US House of Representatives, offers a limited set of reforms. The broader scope of activist demands is illustrated by the Breathe Act, proposed by the Movement for Black Lives, which calls for divesting federal resources from incarceration and policing and investing in new approaches to community safety.2

Such a comprehensive approach, with massive budget implications, is unlikely to win approval even from a majority of Democrats in Congress. But it sets a visionary benchmark for a direction that is increasingly accepted. This direction is reflected in incremental steps being taken in localities around the country, from major cities such as San Francisco to smaller communities such as St. Petersburg, Florida.

Protesters and even some establishment figures, their voices amplified by the mainstream media, warn that current efforts will again fall short unless the nation confronts its legacy of white supremacy, so deeply rooted in history. Symbolic measures are coming first. Confederate monuments and flags, at the forefront of the debate, represent the nation’s original sin of slavery. But statues of Columbus have also been targeted for removal, reflecting the recognition that white supremacy is also based on the nation’s other historical sin: conquest. Andrew Jackson, celebrated by President Trump, symbolizes these twin pillars of white supremacy; his statue was recently removed from the Mississippi city named for him.

The current wave of protests in the United States has received

intense exposure in the global media. The whole world is watching,

as it was during the massive protests of the Vietnam War years. The

response abroad reflects the empathy and solidarity that many

people feel with respect to Black struggles for justice in the

United States. But there is also a recognition that anti-Black

racism is global and not confined to any one country. This racism

shows itself in the treatment of Africans and Afro-descendants in a

wide range of countries, even those without large Black

populations, such as China. It is reflected in the position of the

African continent in the global hierarchy, and in the racial

hierarchy within global institutions.

Protesters outside the United States insist that the history and practices of their own countries must also be questioned. As Kenyan analyst Nanjala Nyabola wrote in Foreign Affairs, the police in Kenya and other African countries continue the colonial practice of institutionalized brutality. In Europe, where demonstrators have denounced police violence and racism, protesters toppled the statue of slave trader Edward Colston in Liverpool, England. Police killings amid pandemic shutdowns in Kenya and South Africa have raised the question of whether Black Lives Matter to African governments; so has the ongoing police violence against civilians in Nigeria.

Despite the heightened attention to police violence in recent years, reporting and statistics from around the world are patchy and inconsistent. Even global human rights organizations, such as Amnesty International, only feature systematic documentation for a few countries, despite the existence since 1979 of an international code of conduct for law enforcement officers. It is generally recognized that police violence is a common feature of authoritarian regimes and of countries engaged in civil wars. But the reality of police violence, disproportionately inflicted on the most vulnerable, is often hidden from public view in most if not all countries around the world.

Nevertheless, looking at the United States in comparative perspective, three points are clear. First, the country consistently ranks highest among developed countries in killings by police relative to population. Second, the pattern closely parallels that of other white settler societies and other countries that were part of European colonial empires, most notably the extreme cases of South Africa and Brazil. And third, global police practices during the 20th and 21st centuries have been and are still deeply influenced by the U.S. example, both through official government links and through the U.S.-based International Association of Chiefs of Police.

In the following section, we review briefly the significant changes in the narratives about police violence and racism that have taken place in recent months. These changes are the result of scholarly critique and activist protests that have mounted steadily for more than a decade.

In a second part of this essay, sent out separately, we first sketch some of the key stages in the evolution of white supremacy and state violence stemming from slavery, conquest of a continent, and overseas empire building. We then look at how the current framework for global military security, prominently including but not limited to the United States military, reflects a destructive logic similar to that of domestic policing.

Changing the Narrative on Police Violence and Racism

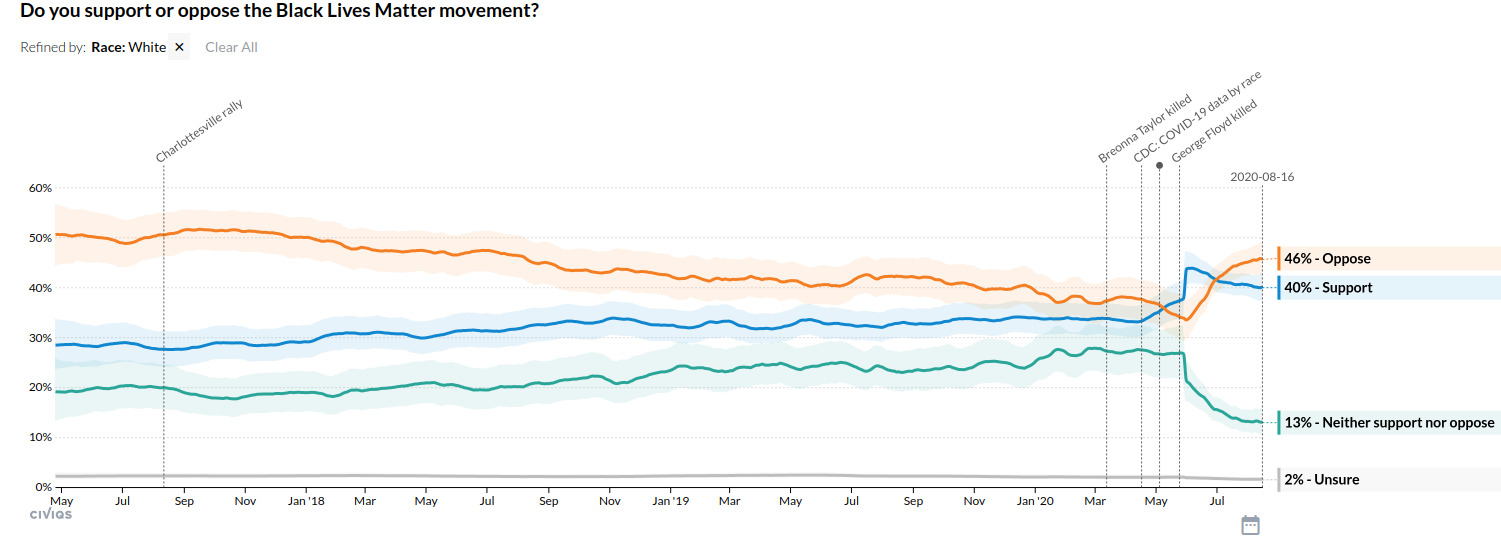

In mid-August the Civiqs daily tracking poll showed that support of Black Lives Matter among registered voters overall was still at almost 50%, compared to 37% opposition. But among whites, levels of support first rose to exceed opposition 44% to 34% before dipping again to 40% support against 46% opposition. Among white Republicans in particular, opposition to Black Lives Matter dipped to a low of 59% in late May, but rose again by mid-August to 78%.

Even if the November election sweeps new leadership into the White

House and Congress, entrenched racism within the police and

other institutions of power will pose a formidable obstacle to

change. And even as protests continue, unexpected events and

Republican messaging may fuel the backlash in favor of white

racism. The movement, it is clear, must have staying power if it is

to accomplish its goals.

The foundation for such staying power consists has been built by

than a decade of work by scholars and activists, and on the

intersection of Black Lives Matter with a wide range of issues and

organizations. It is not concentrated in only one organization but

in mutually reinforcing local and national networks sustained and

expanded by personal connections, by social media, and by common

narratives.

Recent surveys of scholarship undergirding demands for radical change in policing cite dozens of authors.3 One could fill a small library with widely praised books on police violence and racism published in recent years, beginning in 2010 with The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander and The Condemnation of Blackness by Khalil Gibran Muhammad, both recently republished. Other noted titles include White Rage (2016), by Carol Anderson; From #blacklivesmatter to Black Liberation (2016), by Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor; and Making All Black Lives Matter (2018), by Barbara Ransby. In The End of Policing (2018), Alex Vitale provides a concise account of how the expansion of policing in recent decades has accentuated rather than ameliorated the fundamental problems.

In the early years of President Obama’s first term, the most visible protests were from the right, with the rise of the Tea Party. This pattern reflected and intensified the long-standing white backlash against the civil rights advances of the mid-1960s. The murder of Trayvon Martin in 2012 and the acquittal of his murderer in 2013, however, sparked what came to be called #BlackLivesMatter. That movement grew rapidly after the police killing of Michael Brown in 2014. And it has continued to grow, forcing widespread media and public recognition of the reality of disproportionate and unjust police violence against Black men and women. Significantly, the movement, with Black women and LGBTQ people playing central roles, has also modeled an inclusive vision aimed at justice for all, across all the barriers of structural inequality in society.

Also essential to the impact and sustainability of the Black Lives Matter protests is the fact that the movement is rooted in long-standing local campaigns against police violence. To cite just one example, the police station at Homan Square in Chicago had been notorious since the 1960s for systematic brutality, including torture. The abuses were exposed publicly in 1983, and in 1993 the commander, Jon Burge, was fired. In 2014, following appeals from Chicago activists, the United Nations issued a condemnation citing violation of international anti-torture statutes. And in 2015, sustained community campaigns led to a Chicago city council resolution approving a reparations package. In 2020, victims were still waiting for a promised memorial to be constructed.

It is local organizers in Chicago and in cities and towns around the country who have kept Black Lives Matter campaigns going, even during times when the national spotlight was focused elsewhere. At the national level, the Movement for Black Lives, a broad coalition of national organizations and local groups, issued in 2016 a platform of demands, including community control of law enforcement agencies and an end to the war on Black people. Many similar demands were echoed in the plans for criminal justice reform outlined by Democratic presidential candidates, particularly Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren. Even more significantly, activists in other social movements—as well as majority of the Democratic Party—have increasingly been forced to recognize that fighting systemic racism must be part of their agenda as well.

Thus when high school students led national protests for gun control after the killing of 17 people in 2018 in Parkland, Florida, young Black activists reached out to them about the killings in their own communities. Gun violence, the Black youth made clear, is not just a matter of school shootings, but of pervasive racism, a point that the white activists acknowledged. These protests marked a turning point in national opinion, and by the end of 2019, polls showed solid majorities for common-sense gun control measures such as universal background checks and a ban on assault weapons. Gun control activism also primed the young protesters for participation in a wider movement.

The Sunrise Movement, focused on the climate crisis and the Green

New Deal, has been composed mainly of young white people, along

with some non-black people of color. But its activists have stated

explicitly that climate justice implies a commitment to fight

environmental racism. It is no accident that local hubs of the

Sunrise Movement have been actively engaged in the latest round of

Black Lives Matter protests.

The overt racism of the Trump administration has encouraged violent

threats and actions by its white supremacist supporters. This in

turn has spurred anti-Trump forces to recognize that combating

racism is essential to the mobilization against him. The persistent

organizing work of the Black Lives Matter network prepared the

ground for the participation of many whites, especially youth and

women, in anti-racist efforts. Organizational networks such as the

Indivisible Movement were also ready to reinforce the message in

the streets and in local political arenas.

Credit: WDRB News

As protests continue in communities around the country, such as those in Louisville, Kentucky, around the murder of Breonna Taylor, there are many reminders that opposition to reform remains strong. Indeed, the response to protests in Portland, Oregon, shows the ominous potential for federal intervention deliberately aimed at inciting further violence. The images of heavily armed local police and federal agents on the streets of Portland and other American cities have prompted much discussion of the militarization of law enforcement. Through an array of programs, the U.S. government funnels hundreds of millions of dollars in military surplus to local police departments each year.

The notion of policing as a war, in which more lethal force will lead to more security, is not a recent development, but is deeply rooted in U.S. history. The police and the military share the country’s legacy of white supremacy and violence against racial others, which has also given rise to mob and individual violence by white civilians. Both domestic law enforcement and the conduct of foreign wars continue to reflect the history of conquest, slavery, and U.S. empire of earlier centuries.

For the second part of this essay, go to http://www.africafocus.org/docs20/viol2008-2.php

Notes

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication

providing reposted commentary and analysis on African issues, with

a particular focus on U.S. and international policies. AfricaFocus

Bulletin is edited by William Minter.

Current links to books on AfricaFocus go to the non-profit bookshop.org, which supports independent bookshores and also provides commissions to affiliates such as AfricaFocus.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please

write to this address to suggest material for inclusion. For more

information about reposted material, please contact directly the

original source mentioned. To subscribe to receive future bulletins by email, click here.

|