|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

USA/Global: Divest from Violent Policing and Endless Wars, Part Two

AfricaFocus Bulletin

August 24, 2020 (2020-08-24)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

The notion of policing as a war, in which more lethal force will lead to more security, is not a recent development, but is deeply rooted in U.S. history. The police and the military share the country’s legacy of white supremacy and violence against racial others, which has also given rise to mob and individual violence by white civilians. Both domestic law enforcement and the conduct of foreign wars continue to reflect the history of conquest, slavery, and U.S. empire of earlier centuries.

In previous essays in this series, we have argued that significant shifts in views on the home front are opening opportunities for similar changes in policy paradigms at the global level. Such is the case for action on the climate crisis, structural racism and class inequality, and economic rights such as the right to health and the right to a living wage. These trends were already underway early in the year, when we began this series by comparing the foreign policy platforms of the Democratic presidential candidates at the time. Since then, first the Covid-19 pandemic and then the nation-wide uprising against police violence and racism following the murder of George Floyd have accelerated the drive to change the narratives about the need for fundamental change.

In the two AfricaFocus Bulletins sent out today, we explore the

potential and the limitations on making similar links between the

domestic movement against violent policing and the need to make

fundamental changes in the global role of the U.S. military in

escalating violence rather than providing security.

In the first Bulletin, available at http://www.africafocus.org/docs20/viol2008-1.php, we focused on the profound impact of the Black Lives Matter movement from its origin as a hashtag in 2013. In this Bulletin, also sent out today and available at http://www.africafocus.org/docs20/viol2008-2.php, we turn our attention to the deadly feedback loop between policing and empire in U.S. history and to the current status quo of the global U.S. military apparatus.

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins in this series, visit http://www.africafocus.org/usa-2020.php.

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

Divest from Violent Policing and Endless Wars: Invest Instead in a New Social Contract, Part Two

by William Minter and Imani Countess*

* William Minter is the editor of AfricaFocus Bulletin. Imani Countess is an Open Society Fellow focusing on economic inequality. This essay is part of a series entitled “Beyond Eurocentrism and U.S. Exceptionalism: Starting Points for a Paradigm Shift from Foreign Policy to Global Policy,” which began in January 2020. Thanks to Catherine Sunshine for editing the essays in this series.

For the first part of this essay, go to http://www.africafocus.org/docs20/viol2008-1.php

Policing and Empire: A Deadly Feedback Loop

The interactions between policing, racism, and the U.S. military

vary enormously across time and place. In some instances the

relationship is positive. In particular, the two world wars of the

20th century led to advances in international human rights law,

such as the Geneva Conventions and the global human rights system

constructed after World War II. Both within the United States and

around the world, veterans of color returned home to demand that

they and their communities should enjoy the same rights that they

had been fighting for. Their actions contributed decisively both to

the U.S. civil rights movement and to anti-colonial movements

around the world.

Nevertheless, violence against racial “others” has been pervasive, with the history of conquest and slavery feeding into contemporary policing and U.S. wars. This is amply confirmed by recent scholarship and commentaries on the history of U.S. policing, usefully summarized in a New Yorker article by Jill Lepore.

A few examples, ranging over the course of U.S. history up to the

present, well illustrate the point.

Let us briefly consider the iconic Second Amendment, the violent

displacement of Native Americans over centuries, the territorial

expansion of U.S. empire in the late 19th century, and the growth

of domestic policing and its international expansion in the 20th

century.

The Second Amendment was adopted in 1791, after almost two

centuries of colonial settlement in what was to become the United

States. It reads in full: “a well regulated Militia, being

necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people

to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” As historian

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz explains, this historical context is still

relevant despite the passage of more than two centuries and the

expansion of U.S. power across the continent and around the world:

“The elephant in the room in these debates has long been what the armed militias of the Second Amendment were to be used for. The kind of militias and gun rights of the Second Amendment had long existed in the colonies and were expected to continue fulfilling two primary roles in the United States: destroying Native communities in the armed march to possess the continent, and brutally subjugating the enslaved African population.”1

The violent displacement of Native Americans within the territory

that is now the United States began with Spanish settlers in

Florida and New Mexico in the late 16th century, even before

English settlers first arrived in Virginia in 1607. The violence

continued with conquest of the East Coast and New Mexico in the

17th and 18th centuries. Then came the forced expulsion of Native

Americans from the South in the infamous Trail of Tears, under the

Jackson administration in the 1830s, to make way for white settlers

to occupy the land and grow cotton on plantations using slave

labor.

The conquest of the American West, then home to many of the continent’s indigenous peoples, followed in the second half of the 19th century. The assault on Native lands continued in the second half of the 20th century with displacement for construction of dams and, in recent years, pipelines—intrusions that are still being contested.2

From the Spanish-American War of 1898 onward, U.S. wars included

not only the iconic World Wars I and II, but also the construction

and defense of a formal and informal empire that spanned the globe.

August Vollmer is not a household name, but his career trajectory reflects the historical links between policing and the military. He served as the police chief of Berkeley, California, from 1909 to 1923. Vollmer was influential in shaping law enforcement around the country, becoming known as the father of modern American policing and a pioneer in the academic field of criminal justice. His drive to professionalize the police was built on his experience in counterinsurgency in the Philippines after the Spanish-American War.

Vollmer was not an exception. According to historian Stuart Shrader,3 writing in 2014 in the wake of the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri:

“A close look at the history of US policing reveals that the line between foreign and domestic has long been blurry. Shipping home tactics and technologies from overseas theaters of imperial engagement has been a typical mode of police reform in the United States. … From the Philippines to Guatemala to Afghanistan, the history of US empire is the history of policing experts teaching indigenous cops how to patrol and investigate like Americans. … But the flow is not one-way: these institutions also return home transformed.”

This mutual influence has manifested itself in open wars in

Southeast Asia in the 20th century and in Iraq and Afghanistan in

the 21st century. But it has also spawned pervasive global

structures to manage not only these wars, but also the war on

drugs, the policing of immigration, and the post-9/11 war on

terror.

A Global Military

The Breathe Act, proposed by the Movement for Black Lives, includes a demand to dramatically reduce the budget of the U.S. Department of Defense. This is echoed in more detailed proposals put forth by antiwar activists and defense analysts. The global reach of the Black Lives Matter movement implies that a similar reckoning must come for the global security system. Progressives must scrutinize, expose, and challenge the endless wars pursued by the United States military along with the parallel failures of global counterinsurgency and counterterrorism strategies.

United States military spending far exceeds that of any other country, adding up to more than the total of the next nine countries. Despite rising criticism of wasted money and endless wars, however, in late July 2020 significant majorities, including Democrats as well as Republicans in Congress, defeated an amendment to cut 10% from the total Pentagon budget of $740.5 billion. The vote was 324 to 93 in the House of Representatives and 77 to 23 in the Senate.

In contrast to the Vietnam War era, there is currently no strong

antiwar movement in the United States with links to progressive

movements focused on domestic policy. The default assumption in

public debate is that U.S. wars are waged in order to protect the

security of the United States. And with no military draft to spread

the pain widely throughout society—as during the Vietnam War—the

loss of U.S. lives in wars abroad remains largely invisible to the

media and the public. Nonetheless, there are abundant critiques,

across a wide political spectrum, of the U.S. military posture, and

a widely shared uneasiness about “endless wars.”

4

The toll of U.S. wars, of course, is by no means limited to the U.S. personnel who lose their lives. The wars involve a scale of violence against civilians that systematically violates international human rights law, primarily targeting those seen as racially “other.” In the Indochina wars of the 1960s and 1970s, in covert interventions throughout the post-World War II period, and in the Middle East wars and the global war on terrorism of the years since 9/11, there has been little accountability to international standards.5 Moreover, U.S. policy systematically rejects any international obligation to allow independent review of the U.S. military presence around the world.

Violent Repression but No Security

Impunity for abusive state violence and failure to provide security

are more common around the world than respect for the rule of law.

The United States is no exception. It is important to explore the

unique U.S. history and legacy of white supremacy that underpins

the resistance to change. But it is also important to recognize

that the United States, however powerful, is far from alone in its

failures. No nation can claim to have found the solutions or to be

above the need for accountability.

Because of the global scope of its military force, the United States is indeed the largest force for state violence outside its own borders in the current era. But in many active conflicts this country is neither the exclusive nor even the primary factor driving these wars, which are also shaped by internal forces and by other outside actors. As Elizabeth Schmidt has extensively detailed in her two-volume study, the scope, nature, and impact of foreign intervention in Africa varies enormously across cases.6 However iconic, U.S.-dominated interventions such as those in Afghanistan and Iraq are the exception rather than the rule worldwide.

Much more common, throughout the years of the Cold War as well as the post-9/11 era, is U.S. complicity with authoritarian regimes to wage aggression without the presence of large numbers of U.S. troops on the ground. U.S. involvement in such cases can unfold largely without attracting the attention of the U.S. media. The slaughter of as many as one million Indonesians in 1965–1966 has no resonance in U.S. public memory, unlike the Vietnam War. But U.S. officials both encouraged and collaborated with the slaughter of as many as half a million people, directed by the military forces that brought General Suharto to power and kept him in office for 31 years. “Jakarta” became a code word in Latin America for anti-communist mass killings, which the United States supported over decades.7

Whether the United States is actively involved or plays a secondary

role to other actors, however, the post-9/11 counterterrorism and

counterinsurgency wars tend to operate with the same logic. With a

relatively low toll in American lives, they have little visibility

to most of the U.S. public. But these forever wars have produced

mounting costs in U.S. resources as well as violence and insecurity

in the nations where the wars are staged. At best there have been

occasional military victories and temporary restoration of a

semblance of normality. More often, escalation has increased

insecurity and civilian suffering, whether or not U.S. involvement

is front and center.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the region with which the two of us are most

familiar, that pattern is most visible in three long-running

conflicts: the Nigerian army against Boko Haram in Nigeria, the

African Union military mission in Somalia, and French and regional

military forces fighting in Mali and other countries in the West

African Sahel. In all these cases, unlike in the Middle East and

Afghanistan, the United States has a minimal presence of combat

troops on the ground. But U.S. involvement is significant

nonetheless: the United States is training African military forces,

flying armed as well as reconnaissance drones, and mounting

occasional actions by special forces, most notably in Somalia.

Neither the U.S. government nor the affected African governments

are willing to prioritize diplomacy and development over military

aid and arms sales.

8

During the Cold War, extreme repression sometimes bought years or decades of stability for authoritarian governments at the expense of their citizens. In the period following the Cold War and particularly in the post-9/11 period, even nominal stability is elusive, as state violence often provokes increased insurgent violence and/or the growth of organized criminal violence, such as drug trafficking.

This then provides the incentive and the excuse for security forces

to double down on violence. Despite revelations by investigative

journalists, monitoring by human rights organizations, and calls

for reform,the mission and the organizational culture of both the

police and the military ensure that reform efforts are strong on

rhetoric and weak on implementation.

Structural Obstacles Thwart Internal “Reforms”

To some extent, racism, violence, and impunity can be tempered by

reforms within police and military institutions, such as policies

to encourage diversity in the ranks and to prohibit or change

certain practices. The U.S. military is subject to codes of conduct

such as the Geneva Conventions, the United Nations Convention

against Torture, and the U.S. Uniform Code of Military Justice.

Some local jurisdictions have attempted to reform their policing

through measures such as barring chokeholds, requiring use of body

cameras, and establishing civilian review boards to investigate

misconduct.

These reforms can have some limited effects, but they are by no means universally applied. There are significant differences among agencies, within both law enforcement and the military, with respect to the rule of law. Many officers in the U.S. military hold strong personal commitments to professional codes of conduct; this is reflected in the rising tensions between some levels of the military and the lawless Trump administration.9 Among federal and domestic law enforcement agencies, norms, policies, and practices are highly variable. In times of crises, these differences between agencies will continue to be central in the choices either to escalate violence or to deescalate violence while considering alternatives.

However, the organizational culture of security agencies is most

often highly resistant to significant reforms or checks, and

credible penalties for violations are rarely enforced. Moreover,

the criteria for “success” in achieving their missions—numbers of

enemy forces killed in war, arrests made in policing—are not

measures of success in achieving actual security. Continued threats

are turned into justification for increased budgets and for

doubling down on failed strategies.

Without external accountability for violations of human rights and

for ineffective policies, internal reforms can only have marginal

impacts. And vested interests in violent organizational cultures,

growing in proportion to exorbitant budgets, create strong

incentives for politicians to avoid enforcing outside

accountability.

Shifting Resources through Divestment and Investment

The domestic debate on police violence has significant momentum,

with continuing local protests and high national visibility. A

central question is whether, how, and to what extent localities

should divest from violent policing and reinvest some funds in

alternative means to ensure community security.

With U.S. military engagement abroad largely invisible to the wider

U.S. public, there is no parallel, high-profile debate on the role

of the U.S. military in fomenting global violence, nor much public

discussion of redirecting the Pentagon’s budget or priorities. The

U.S. military itself is unlikely to question the fundamental

premises of its global engagement, which centers on the competition

with major powers such as Russia and China. The traditional

conception of security—as protection against violent threats from

enemies—largely persists. And the vested interests and policy

assumptions that protect funding for the military-industrial

complex are even more strongly entrenched than those that defend

local police budgets.

But there is also a strand of strategic thinking and internal criticism within the defense community that is open to considering other threats to security, most notably global disease pandemics and climate change. A notable example is the internal military investigations of the impact of climate change. In his new book All Hell Breaking Loose, Michael Klare analyzes internal Pentagon documents, finding evidence that “of all major institutions in U.S. society, none is taking climate change as seriously as the U.S. military.”10

Military planners realize that they must prepare for complex

clusters of climate disasters, such as the sequence of Hurricanes

Harvey, Irma, and Maria in 2017. Such events have already stretched

the military’s capacity for humanitarian response and pose a

growing threat to military bases, both within the United States and

around the world. The military has focused its planning more on

adaptation to climate change than on mitigation by reducing carbon

emissions. But it has also taken steps to diminish its reliance on

fossil fuels through proactive research and investment in renewable

energy. And it is acutely aware of the likely increase in

instability due to the effect of climate crises in areas already

plagued by other causes of conflict.

These Pentagon reports and their implications have not been widely publicized, given the imperative not to openly contradict the climate-denying commander-in-chief. But under different national political leadership, some military voices could potentially be advocates for addressing the causes, rather than only the consequences, of rising conflicts. This would also require rethinking the mission of counterterrorism and counterinsurgency.

No single conflict, in Africa or elsewhere, currently has the potential to shift thinking about fundamentals of the U.S. global military posture. Even Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen, which earned bipartisan condemnation, is discussed only as an exceptional case. Nor is the movement to curb violence within the United States likely to fully extend its scope to the global arena. What can have significant effects, however, are the fiscal pressures from new initiatives on other issues, such as the Green New Deal and Medicare for All. And changes in the Pentagon’s priorities may also come, in indirect ways, from its own research and planning to deal with the climate crisis, the threat of pandemics, and other humanitarian crises. Those factors, together with the emerging consensus against endless ground wars, have potential to eventually change the minds of Republican as well as Democratic voters.

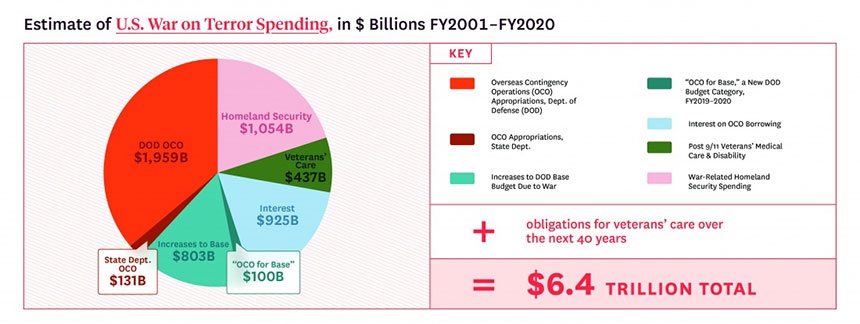

Credit: Costs of War Project

The costs of the post-9/11 wars have been well documented by the Brown University Costs of War Project, with a budgetary cost of $6.4 trillion through fiscal year 2020. Peace activists and analysts have advanced credible alternatives to save on military spending.11 Polls from foreign policy establishment organizations may highlight support for ongoing military alliances as essential to U.S. global engagement. But when other pollsters asked more detailed questions, 58 percent of Republicans and 79 percent of Democrats supported ending U.S. ground wars.

When asked to identify the top threats to our security, a plurality

of voters (46 percent), and 73 percent of Democrats, said that the

US primarily faces nonmilitary threats. In light of the covid-19

pandemic, along with disastrous hurricanes, fires, and floods,

public pressure for spending on such other threats is likely to

grow. And critics will find many in the military who agree with

them.

Trump has vowed to end wars, but this is a false promise, notes Peter Certo in Foreign Policy in Focus. Democratic candidates, for their part, have not yet taken full advantage of public disenchantment with shooting wars to advance a robust agenda of funding for alternative security initiatives.

A New Social Contract?

In the previous essays in this series, we argued that significant

shifts in views on the home front open an opportunity for similar

changes in policy paradigms at the global level. Such is the case

for action on the climate crisis, gross economic inequality, and

economic rights, such as the right to health and the right to a

living wage. The major obstacle is political will rather than lack

of compelling alternative visions, which are now highly visible in

public debate. The same applies to state violence, although the

potential for domestic change on this front is still much more

visible than the alternatives to global U.S. military overreach.

The current convergence of global crises, none of which shows any

signs of ending, threatens mass devastation on the scale of the

Great Depression and World War II, in the United States and around

the world. In rapid succession in 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic, its

economic repercussions, and resistance to state violence have had

unprecedented cumulative effects. While further turmoil is

inevitable, this might also offer the opportunity for fundamental

changes—if urgent demands for immediate action are grounded in an

understanding of the deep roots of injustice and the global scope

of the challenge.

One of the most striking signs of hope is the fact that progressive

activists as well as many mainstream analysts are seeing the issues

not as isolated and competitive but as linked and complementary.

The Black Lives Matter movement has continuously stressed the

intersectionality of identities and issues. More and more activists

are following their lead, which implies focusing on providing

mutual aid and solidarity across boundaries of all kinds, including

national borders.

Policy changes to implement such a vision will not be easy. One

measure of success, whether at the local, national, or global

level, will be to what extent government budgets begin to shift

from investing in state violence to social investment in fulfilling

a new social contract.

Notes

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication

providing reposted commentary and analysis on African issues, with

a particular focus on U.S. and international policies. AfricaFocus

Bulletin is edited by William Minter. For an archive of previous Bulletins,

see http://www.africafocus.org,

Current links to books on AfricaFocus go to the non-profit bookshop.org, which supports independent bookshores and also provides commissions to affiliates such as AfricaFocus.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please

write to this address to suggest material for inclusion. For more

information about reposted material, please contact directly the

original source mentioned. To subscribe to receive future bulletins by email,

click here.

|