|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

Confronting Global Apartheid Demands Global Solidarity

AfricaFocus Bulletin

April 19, 2021 (2021-04-19)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

"The COVID-19 pandemic has both revealed and deepened structural

inequalities around the world. Nearly every country has been hit by

economic downturn, but the impacts are unevenly felt. Within and

across countries, the people who have suffered most are those already

disadvantaged by race, class, gender, or place of birth, reflecting

the harsh inequality that has characterized our world for centuries."

Regular readers of AfricaFocus Bulletin will already be familiar with the US-Africa Bridge Building Project, founded by Imani Countess, on which I am working as a consultant. This AfricaFocus Bulletin contains the first essay in the project's Transnational Solidarity Playbook, which is being released on the project website today. The format for that website was designed by Go!Creative and Village Green Consulting, and is much more professionally designed and attractive than the workable but out-of-date home-made format constructed for AfricaFocus by your editor more than 15 years ago.So do check out the links above in this paragraph.

That essay is accompanied by excerpts and an embedded video from the Steve Biko Memorial Lecture by Angela Davis in South Africa in 2016. Other original essays as well as other material for the Playbook will appear in later months, authored by a diverse set of authors with activist experience and scholarly knowledge of a range of transnational solidarity movements.

For an earlier set of essays by Imani Countess and me based on similar perspectives, see "Beyond Eurocentrism and U.S. Exceptionalism: Starting Points for a Paradigm Shift from Foreign Policy to Global Policy," at http://www.africafocus.org/usa-2020.php.

For another recent article on U.S. policy and Africa, by Elizabeth Schmidt and me, published on April 8, see https://responsiblestatecraft.org/2021/04/08/in-africa-an-acknowledgement-that-counterterrorism-has-failed/.

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

Confronting Global Apartheid Demands Global Solidarity

by Imani Countess and William Minter

This essay is part of a series that will be included in a Transnational Solidarity Playbook to be published by the US-Africa Bridge Building Project. The series is based on the premise that progressive forces must increase our capacity to join forces across national borders, defeat authoritarian regimes and movements based on hate, and find the strength to build a future based on common humanity and justice for all.

Imani Countess is the project director for the US-Africa Bridge

Building Project. William Minter is a consultant for the Project and

the editor of AfricaFocus Bulletin.

The COVID-19 pandemic has both revealed and deepened structural

inequalities around the world. Nearly every country has been hit by

economic downturn, but the impacts are unevenly felt. Within and

across countries, the people who have suffered most are those already

disadvantaged by race, class, gender, or place of birth, reflecting

the harsh inequality that has characterized our world for centuries.

This deepening inequality haunts our global future. According to a report released by Oxfam in January 2021, “Billionaire fortunes returned to their pre-pandemic highs in just nine months, while recovery for the world’s poorest people could take over a decade.”

International scientific collaboration has yielded multiple vaccines against the novel coronavirus. But the most vulnerable people and countries have been last in line for doses, or are not in line at all, threatening a vaccine apartheid. If that continues, it will be impossible to end the pandemic, as the virus will continue to mutate and spread across borders.

“Global apartheid” is more than a metaphor

The term “apartheid” comes from South Africa, notorious in the 20th

century as the last stronghold of white minority rule. Political

apartheid in South Africa ended in 1994 with free elections open to

South Africans of all races. But South Africa and the world are still

embedded in an international system of inequality reflecting the

history of European conquest and domination.

In this system, wealth and power are still structured by race and place, both within and between nations. Whether or not one labels it global apartheid, there are striking parallels with South African apartheid.

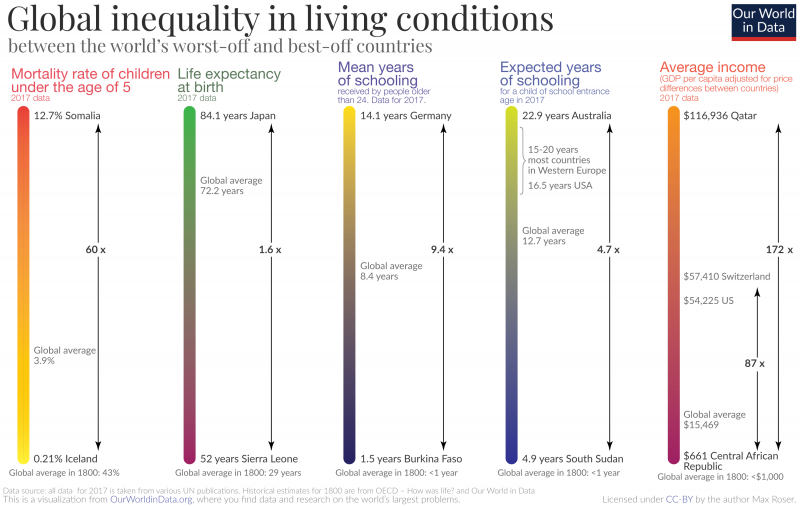

Credit: Our World in Data, 2017

In July 2020, UN Secretary-General António Guterres, in the annual Nelson Mandela lecture, addressed what he called the “inequality pandemic” and called the world to a “new social contract.” Such a contract, it is clear, will not happen quickly. But it will not happen at all unless millions around the world mobilize to make it happen.

South African apartheid was part of a global system of unequal rights

South Africa shares a history of white supremacy with other white settler states, including the United States, as Senator Robert Kennedy acknowledged in a speech to students in Cape Town in 1966. Its apartheid regime was part of a world order defined for centuries by hierarchies of racial privileges both between and within countries.

Since the discovery of diamonds and gold in the late 19th century,

South Africa and its neighbors in the Southern African region had

been linked closely to Western economies, particularly the United

States, England, and continental Europe. Internally, apartheid in

South Africa was a multilevel system of labor control and

differential rights, paralleling the global hierarchy. There were

gradations of privilege for whites, Asians, “Coloured,” and

“natives,” as well as for “natives” in urban areas, those in rural

“homelands,” and “foreign natives.”

Beginning in the 1960s, when independent African countries joined the United Nations, the end of political apartheid played out on a global stage. Exposure of the South African regime’s inhumanity, including forced labor, torture, and attacks on neighboring states, led the United Nations General Assembly in 1974 to designate apartheid as a crime against humanity.

Transnational solidarity was essential to the anti-apartheid movement

Over the next two decades, the regime maintained highly visible

repression within its borders while also waging proxy wars that

devastated the entire Southern African region. The human toll on

South Africans and their neighbors mounted into millions of lives

lost. South Africa’s Western allies, despite growing willingness to

speak against apartheid, stubbornly maintained their military and

economic ties with the regime.

In opposing white minority rule, the South African liberation

movements relied on mobilizing internal opposition, but they also

issued appeals for support worldwide. They called for sanctions

against the white minority regime and for direct support for South

African liberation, including support for armed struggle. This

outreach was essential because of the extent to which rich Western

countries both profited from and sustained the South African economy

and state.

Those calls were answered in different ways by governments, by

multilateral bodies such as the Organization of African Unity and the

United Nations, and by hundreds of solidarity organizations in almost

every country of the world.

Solidarity was based on the recognition of common humanity

By the 1980s it was possible to speak of a transnational anti-

apartheid movement. But it was a movement that drew in many different

constituencies, with varying connections to and understandings of the

situation in South Africa. For people in Africa and other world

regions who had themselves experienced European conquest and colonial

rule, the connection was clear. In the United States, too, the long

history of the Black freedom movement closely paralleled that in

South Africa. And the entire world recalled the anti-fascist struggle

of the mid-20th century and its promises of freedom. South Africans

seeking solidarity understood that they were speaking to specific

audiences, not to an undifferentiated global community, and they

strove to meet people where they were.

The fundamental message of the transnational anti-apartheid movement

was, and remains, equal rights for all, applicable not only in South

Africa but around the world. We must learn to live and work together

on the basis of our common humanity, as expressed in the African

concept Ubuntu.

That does not mean calling for neutrality or covering up the

realities of injustice and oppression. It does mean rejecting the

principle of separation (the literal meaning of “apartheid”) and

bringing people into more inclusive communities with a common vision

of justice for all.

Collective action relied on diverse strategies and multiple

constituencies

In the 1980s, activists developed a range of collective action

strategies to support South African calls for political liberation.

These included divestment of corporate, pension, and municipal funds

from institutions invested in apartheid, as well as protests,

mobilizations, and campaigns. Local activists used their own

experience and knowledge of specific places and specific institutions

to craft appropriate strategies and tactics.

The movement drew in politicians and civil servants in national

governments, staff of multilateral institutions, leaders of

religious, student, trade union, professional, and social justice

organizations, and grassroots leaders in local communities. These

diverse actors built collective power and worked together for a

common cause. In doing so, they had to look beyond racial and

national divides, work through internal debates about strategy, and

overcome conflicts driven by ideology and personal ambition.

The same general principles apply today to movements confronting a

global pandemic, the climate crisis, and rising overt threats from

authoritarianism, xenophobia, and racism. But today's global

movements must also confront not only new global realities but also

enduring injustices not addressed by the anti-apartheid movement or

other national freedom struggles of the 20th century.

The victory against South African apartheid was real but incomplete

The victory we celebrated with the election of Nelson Mandela in 1994

was real, as were earlier victories in freedom struggles in other

times and places. But that victory was by no means complete.

Democratic political rights, in South Africa or any other country,

are essential prerequisites for social and economic justice – but

provide no guarantees. Indeed, the 21st century has brought steadily

widening inequality and mounting threats to democracy, in South

Africa and in countries around the world.

Today we have a new set of intersecting crises, with the

authoritarian playbook of “divide and rule” gaining ground in many

countries. In meeting this moment, we can take inspiration and

guidance from the collective victories of earlier generations. We

must take seriously the truth that none of us are free until all

of us are free. This principle, voiced over the years by Emma

Lazarus, Fannie Lou Hamer, and Martin Luther King Jr., must apply

across all the intersecting divisions that separate us from each

other, including national borders as well as the familiar triad of

divisions by race, class, and gender.

The transnational anti-apartheid movement is one powerful

illustration of how this principle can be applied. First, the

movement built strong personal and organizational ties across borders

in commitment to a common cause. Second, global leadership came from

those most endangered by South Africa's apartheid regime, namely

movements in South Africa and its neighboring countries.

But that movement also had internal shortcomings. The greatest

limitation, as in other movements targeting national, racial, or

class injustice, was the failure to address gender injustice. Despite

public celebration of women in the struggle, failure to listen to

women’s voices, and even tolerance of gender violence, was more the

rule than the exception. That remains the case today worldwide,

despite the profusion of pledges to address gender equity.

New movements give hope for global solidarity

Over the past decade, as global inequalities have deepened, a wave of

movements has been charting new strategies and paths forward. These

movements include, to give just a few examples, Black Lives Matter,

the climate justice movement, movements for women's rights and LGBTQ

rights, and union organizing among care workers and those in the

informal economy, who are disproportionately women and youth.

These emergent movements build on new understandings of history as well as on an analysis of the current moment. As Angela Davis noted in the Steve Biko Memorial Lecture in 2016, our work must be rooted in history yet must go beyond the limitations of the past. That means building structures that raise the voices of those who have been barred historically from leadership positions in social change movements. From the local to the global level, organizations and movements must feature “inclusiveness, interconnectedness, interdependency, intersectionality, and internationalism,” Davis told the audience at the University of South Africa.

The obstacles may seem overwhelming. But we can redefine the possible, argues Varshini Prakash of the Sunrise Movement, the youth movement that has put the Green New Deal at the center of the political debate on climate change in the United States. “In your demands and your vision, don't lead with what is possible in today's reality but with what is necessary.”

Whether on climate, on the Covid-19 pandemic, or on rising

inequalities by race, gender, class, and place of birth, joining

forces for justice across national boundaries is not a choice. It is

a necessity.

A movement, not just a leader

by Imani Countess

Nelson Mandela, the imprisoned leader of the African National

Congress, was the best-known face of the anti-apartheid movement.

Millions around the world watched as Mandela was released from prison

in February 1990.

Two months later, I sat in London’s Wembley Stadium with 70,000

others celebrating Mandela’s release and the start of a difficult but

hopeful transition in the movement against political apartheid.

Several Americans sat in front of me. It turned out they were from

Pikesville, Maryland; I was born and raised in nearby Baltimore.

Pikesville was a majority-white suburb of folks who fled the city in

the 1960s and ’70s in response to desegregation efforts. Nonetheless,

there we were in London, joined together in celebrating the success

of a transnational solidarity movement led by Black and Brown South

Africans.

That movement included not only iconic leaders like Mandela, but also

grassroots leaders not in the international public eye. Just as

important, it included countless activists around the world – a

complicated mix of campaigners, national liberation parties,

political formations and organizations, UN agencies, faith-based

organizations, unions, students, and scholars.

Such a coalition is just as essential in confronting today's global apartheid.

|

Selected Resources on the Transnational Anti-Apartheid Movement

Have You Heard from Johannesburg?

https://www.clarityfilms.org/haveyouheardfromjohannesburg/

7-part video series on the transnational anti-apartheid movement, available as video-on-demand.

The Road to Democracy in South Africa: International Solidarity

http://www.sadet.co.za/road_democracy_vol3.html and http://www.sadet.co.za/road_democracy_vol5.html

Extensive studies by South African and other scholars from the South African Democracy Education Trust. Some chapters are downloadable.

African Activist Archive Project

https://africanactivist.msu.edu/

On-line digital documentation (more than 10,000 items) from national and local activist groups in the United States

The Anti-Apartheid Movement

https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/anti-apartheid-movement-aam

Brief summary and selected documents from South African History Online

Walter Bgoya: From Tanzania to Kansas and Back Again

http://www.noeasyvictories.org/select/04_bgoya.php

The key role of Tanzania in Southern African liberation struggles

O. R. Tambo’s forgotten speech at Chatham House

https://mg.co.za/africa/2020-07-09-exclusive-or-tambo-chatham-house-speech/

Speech by ANC President Oliver Tambo, 1985

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication

providing reposted commentary and analysis on African issues, with

a particular focus on U.S. and international policies. AfricaFocus

Bulletin is edited by William Minter. For an archive of previous Bulletins,

see http://www.africafocus.org,

Current links to books on AfricaFocus go to the non-profit bookshop.org, which supports independent bookshores and also provides commissions to affiliates such as AfricaFocus.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please

write to this address to suggest material for inclusion. For more

information about reposted material, please contact directly the

original source mentioned. To subscribe to receive future bulletins by email,

click here.

|