|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

Africa/Global: Decolonizing Medical Technology

AfricaFocus Bulletin

May 17, 2021 (2021-05-17)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

“A continent of 1.2 billion people should not have to import 99% of its vaccines. But that is the tragic reality for Africa. Fixing the lack of home-grown manufacturing capacity has become a top priority for Africa’s policymakers. Last week, 40,000 people, including researchers, business leaders and members of civil-society groups, joined heads of state for a two-day online summit designed to share the latest developments and kick-start fresh thinking on how to bring vaccine manufacturing to Africa.” - Nature magazine editorial, April 21, 2021

Covid-19 has revealed the urgency of reducing the inequality in global access to vaccines, prompting a wide-ranging and ongoing debate about what must be done about what many are calling “vaccine apartheid.” But, as stressed in this summit convened by the Africa CDC and the African Union, the issue goes beyond any single disease, to the need to plan for future pandemics and address the inequities in capacity in both research and manufacture of vaccines.

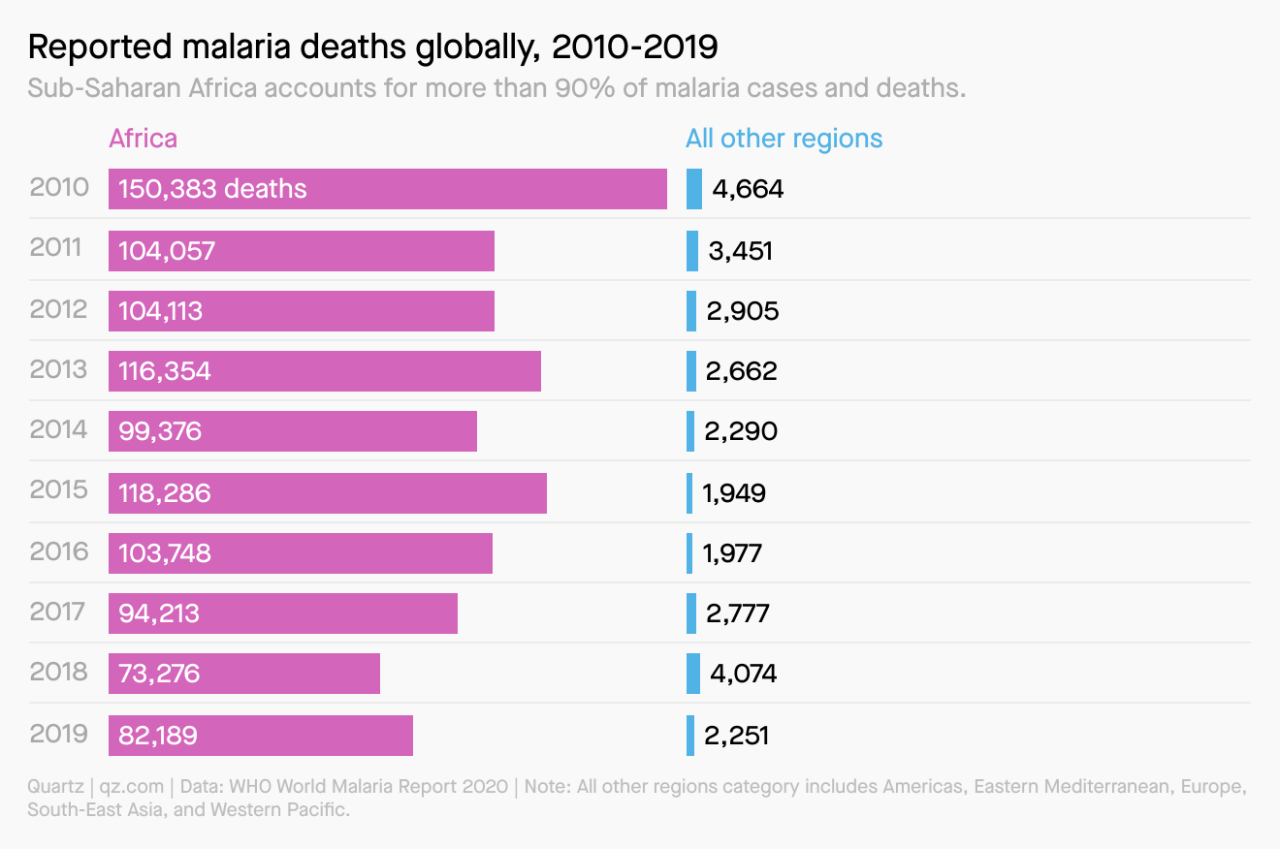

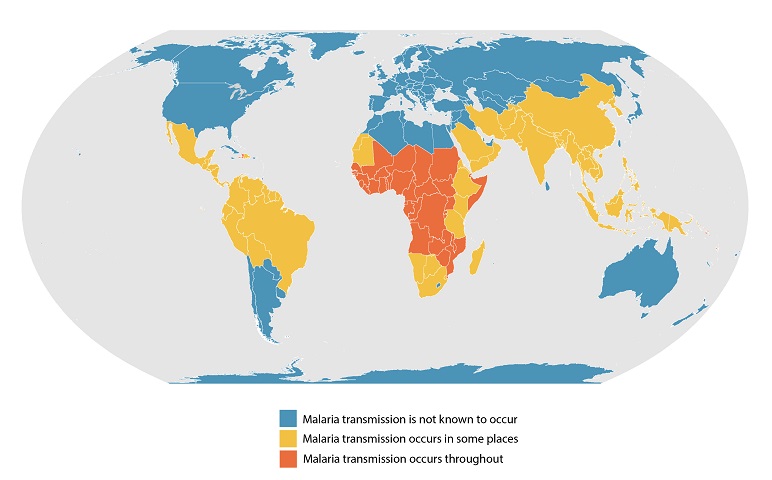

This is already the case for malaria. A new vaccine with over 70% of efficacy was first reported earlier this month. African and world leaders and health officials are increasingly focused on the possibility of accelerating the fight against this deadly disease, which in 2019 caused over 84,440 deaths world-wide. Ninety-seven percent of those deaths were in sub-Saharan Africa. So while global campaigns under the slogan of “Malaria Must Die” continue, it is clear that the initiative for action must come from Africa.

Even once vaccines are available, there will remain formidable problems of manufacturing and distribution. On April 13, African leaders pledged to increase the share of vaccines manufactured in Africa from 1% to 60% by 2040. It will not be easy.

This AfricaFocus Bulletin includes (1) key links on the current status of the fight against malaria, (2) an open letter to international funders from African researchers, reposted here in full with permission from Nature magazine; and (3) excerpts from a news story and an editorial in Nature magazine on the urgency of development of vaccine capacity in Africa.

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on health, visit

http://www.africafocus.org/intro-health.php

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Two additional notes about this Bulletin

1. Unlike many if not most readers of AfricaFocus, including my wife, I have never had malaria, despite a total of more than five years spent in areas of the continent where the disease is endemic. But my awareness of the disease began long before I first traveled to Africa. My father, Dr. David Minter, served as a malaria control officer in the South Pacific during World War II, where in the early years the disease caused more casualties among U.S. troops than the Japanese military. Atabrine, DDT, and education of the troops brought the toll down significantly.

Unlike many wartime assignments, his posting to this position made good sense, as he had several years of experience in treating malaria in the 1930s in Mississippi, where malaria was endemic before the war.

His colleague in the South Pacific in this effort, Filipino physician Dr. Francisco Dy, who later served as the World Health Organization regional coordinator for the Western Pacific, became a life-long friend of my parents.

2. With this Bulletin, I am including a short embedded video featuring the Kanneh-Mason family cover of Bob Marley's Redemption Song. I may make this a regular feature of the Bulletin, featuring short music videos that do not take up extra bandwidth in the email. The idea came from the editors of Quartz Africa, who often end their weekly email with a note saying “written while listening to.”

I am not good enough at multi-tasking to listen while I write. But I do find it necessary to take short breaks from writing to listen and watch short music videos. That is essential for the spirit, particularly when one is writing about subjects which more often feature grim realities than hope for change. The videos I will choose for inclusion are not linked to the specific theme of the Bulletin. But they definitely illustrate the visions of the resilience and hope needed both by Africa and the world.

I hope some of you enjoy them. If you don't, it's easy not to watch. They aren't set to auto-play.

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

Recent news and background on malaria

https://theconversation.com/new-malaria-vaccine-proves-highly-effective-and-covid-shows-how-quickly-it-could-be-deployed-159585

https://qz.com/africa/2005934/africa-can-avoid-covid-19-vaccine-missteps-with-malaria-vaccine/

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malaria

https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/about/distribution.html

https://allafrica.com/malaria/

https://allafrica.com/stories/202105040682.html

Meeting of African Leaders Malaria Alliance

https://malariamustdie.com/

World campaign against malaria, headlined by David Beckham

*******************************************************

Open letter to international funders of science and development in Africa

April 15, 2021

Nature Medicine, April 15, 2021

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-021-01307-8

From Ngozi A. Erondu? ?1,2;, Ifeyinwa Aniebo 1,3,4; Catherine Kyobutungi 5; Janet Midega1, 6; Emelda Okiro 7; and Fredros Okumu 1,8.

1 Aspen Institute, Washington, DC, USA; 2 O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law, Georgetown University Law Center, Washington, DC, USA; 3 Health Strategy and Delivery Foundation, Lagos, Nigeria; 4 Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA;

5 African Population Health Research Center, Nairobi, Kenya; 6 Wellcome Trust, London, UK; 7 KEMRI Wellcome Trust Research Programme, Nairobi, Kenya; 8 Ifakara Health Institute, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Contact email for authors: ngozierondu@gmail.com

To the Editor—Recently there was an announcement1 of a US$30 million grant awarded to the nonprofit health organization PATH by the US government’s President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI). The grant funded a consortium of seven institutions in the USA, the UK and Australia to support African countries in the improved use of data for decision-making in malaria control and elimination.

Not one African institution was named in the press release. The past year has been full of calls from staff and collaborators of various public-health entities for equality and inclusion, so one might imagine that such a partnership to support Africa should be led from Africa by African scientists, partnering with Western institutions where appropriate, especially where capacity has been demonstrated.

We write this letter to the major international funders of science and development in Africa as African scientists, policy analysts, public-health practitioners and academics with a shared mission of improving the health and wellbeing of communities in our continent and beyond. We represent a diverse group of institutions and communities dedicated to achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals and to establishing a more equitable world.

Our work is informed by lived experiences and accumulated local knowledge of diseases such as malaria, AIDS, diarrhea, meningitis and polio, which have plagued millions of our families and friends for ages. We are therefore grateful that organizations that fund international health research have long been part of the international efforts to rid the world of these illnesses and their associated inequities. We believe the reason these organizations are financing global health and development is that they share in our dreams and aspirations.

We also believe, just like you, the decision-makers at these major funding organizations, that all humans, regardless of where they are located, are equal, even if opportunities are not. We recognize multiple injustices that have been perpetuated through historical practices, often without due consideration of their negative consequences. The current political climate has amplified the global call to ‘decolonize global health’, a more overt stance against what public-health practitioners in both high-income countries and low-income countries have known all along: that the predominant global health architecture and its business model enable ‘western’ institutions to gain more than, and sometimes at the expense of, the people and institutions in the countries where the actual problems are.

As the ‘decolonize global health’ movement has demonstrated, dismantling structures that perpetuate unequal power over knowledge and influence must support the quest for justice and equality. Global health institutions, especially funding organizations, must therefore examine their own internal policies and practices that impede progress toward justice and equality for populations that they intend to help. We write this letter as a collective, hoping to accelerate, and in some cases initiate, a process toward real fairness. We believe that there are many issues with this specific consortium focused on malaria, including the fact that there are strong African institutions with excellent capabilities this area, including some already actively engaged on the ground, such as the KEMRI Wellcome Trust Information for Malaria (INFORM) initiative that began in 2014 (http://inform-malaria.org/).

International funding, such as that from the President’s Malaria Initiative, has substantially advanced the goal of improving people’s health and wellbeing in Africa and beyond. However, funding models such as that of the PATH-led initiative are among the reasons that after several decades and billions of dollars spent, the control of diseases such as malaria is still heavily donor dependent, This type of funding has also contributed a model of implementation that puts the delivery of several health interventions directly in the hands of Western non-governmental organizations, which further diminishes the capacities and ownership of national programs to deliver to their populations and ultimately leads to weak health systems and a lack of sufficient local capacity. Decisions about such major funding initiatives should be made in consultation with in-country scientists and researchers involved in this work, alongside ministries of health and national malaria-control programs, to augment national priority research efforts. Such efforts have the best chance of success if they are run by local research agencies and institutions that can work closely with governments and are well positioned to support decision-makers in integrating data into local policies and strategies.

The new ‘high burden to high impact’ initiative from the World health Organization rightly recognizes the need for such vital work to be country-owned and country-led to reignite the pace of progress in the global fight against malaria and to increase the likelihood of success in eliminating malaria. Omitting African institutions from leadership roles and relegating them to recipients of ‘capacity strengthening’ ignores the agency these institutions have, their existing capacity, the value of their lived experience and their permanence and close proximity to policy-makers.

In 2017, the USA, UK and Canada collectively spent US$ 1.1 billion on malaria development aid, which includes research funding. When the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation data-visualization tool is used (https://vizhub.healthdata.org/fgh/), it appears that once global fund contributions are removed, 81% of funding was used to support institutions in the funding country and 18% went to non-governmental organizations (probably based in high-income countries)—that leaves just 1% of malaria funding available to local in-country research institutions. We recognize that the current funding structures create an imbalance of power and a monopoly that favors Western institutions and is derived in part from the perpetuation of inequities in access to funding with policies that lock out African institutions. These structural inequities must be examined, and they must end.

We know that several decision-makers of these organizations recognize the limitations of the model that you have woefully applied to the issue of which we speak. The New Partnerships Initiative from the US Agency for International Development (https://www.usaid.gov/npi) and the Alliance for Accelerating Excellence in Science in Africa (https://www.aasciences.africa/aesa) are good examples of funding local institutions for impact. The latter is shifting its center of gravity by ensuring its funding is provided directly to African scientists and institutions, which in turn empowers and enables them to shape their research agenda and to conduct research relevant to the continent. But we argue that these are the exceptions. For long-term progress, true partnerships and stronger collaborations, you, the funders, are responsible for totally transforming this model. We believe that in the same way we have to apply innovation in our work to fight diseases, innovation can be applied to the design of sustainable funding models with local researchers and organizations at their center.

We are asking that all major international funders of science and development in Africa commit to finding and implementing short-term and long-term changes to these models with consideration of the points we have listed above and with further consultation with reputable Africa-based institutions and scientists. There is a way to create equitable and dignified partnerships and to defeat the diseases that threaten everyone. We who authored this Correspondence are few, but we are committed to assisting any organization that is willing to make a substantial change.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01307-8

References

1. PATH. https://www.path.org/media-center/path-announces-pmi-inform-malaria-operational-research-project/ (10 February 2021).

2. World Health Organization & RBM Partnership to End Malaria. High burden to high impact: a targeted malaria response (WHO, 2019).

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the original drafting, reviewing, and editing of this letter and gave final approval of the version to be published. This letter is signed in an individual capacity. The views and opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect that of any organization they (the authors) are associated with or employed by.

************************************************************

How COVID spurred Africa to plot a vaccines revolution

For decades, Africa has imported 99% of its vaccines. Now the continent’s leaders want to bring manufacturing home.

Nature magazine, April 21, 2021

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-01048-1

[excerpt from full news story available at link above]

Prompted by the pandemic, Africa’s leaders are on a path to ramp up

capacity in vaccine manufacturing and boost the continent’s

regulatory bodies for medicines. On 13 April, they pledged to

increase the share of vaccines manufactured in Africa from 1% to 60%

by 2040. This includes building factories and bolstering capacity in

research and development.

The COVID-19 pandemic has left Africa woefully short of vaccines,

according to John Nkengasong, director of the Africa Centres for

Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC), based in Addis Ababa.

The ambitious move represents an important step in boosting Africa’s

capacity in public health, he added.

Nkengasong was speaking at a 2-day vaccines summit on 12 and 13

April, co-organized by Africa CDC and the African Union, and attended

by 40,000 delegates. Also taking part were heads of state and leaders

from research, business, civil society and finance.

“We have been humbled, all of us, by this pandemic,” said Abdoulaye

Diouf Sarr, Senegal’s minister of health and welfare. The 1% figure

“boggles the mind”, added virologist Salim Abdool Karim, formerly a

science adviser to South Africa’s government.

. . .

In the next pandemic, will Africa make its own vaccines?

The AU meeting ended on an upbeat note, with delegates talking of

“tipping points”, “now-or-never moments” and “global goodwill” to

enable Africa to finally create its own vaccines industry. Progress

will need political commitment, long-term finance and regional

cooperation, said Patrick Tippoo, executive director of the African

Vaccine Manufacturers’ Initiative, a group of vaccine manufacturers

and research institutes.

The foundational problem, Tippoo added, is that the continent’s

leaders have lacked the vision to recognize the centrality of local

vaccine manufacturing in health-care policy.

The lack of manufacturing and weak regulation will require long-term

governmental support if they are to be overcome, said Solomon

Quaynor, a vice-president at the African Development Bank Group.

Without such support, he warned the meeting’s delegates, “there will

be no vaccine manufacturing in Africa”.

But momentum is on the side of new beginnings. “In the final

analysis, the onus is on us as Africa. I do know we can do the job,”

said Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, Nigeria's former finance minister and now

director-general of the World Trade Organization.

*************************************************************

Africa’s vaccines revolution must have research at its core

It’s an injustice that Africa has to import 99% of its vaccines. COVID has sparked a push for change — and researchers have a crucial role.

Nature magazine, April 21, 2021

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-01038-3

[excerpt from full editorial available at link above]

A continent of 1.2 billion people should not have to import 99% of

its vaccines. But that is the tragic reality for Africa. Fixing the

lack of home-grown manufacturing capacity has become a top priority

for Africa’s policymakers. Last week, 40,000 people, including

researchers, business leaders and members of civil-society groups,

joined heads of state for a two-day online summit designed to share

the latest developments and kick-start fresh thinking on how to bring

vaccine manufacturing to Africa.

For more than a century, vaccine research and development (R&D) and

manufacturing have been concentrated in Europe, India and the United

States. Amid a raging pandemic, one result of this is that people in

low- and middle-income countries might have to wait until the end of

2023 before they can be vaccinated against COVID-19. This is simply

unacceptable.

Delegates at last week’s summit vowed to accelerate plans to boost

the continent’s vaccine manufacturing, research and regulatory

capacity. They endorsed a proposal for 60% of Africa’s routinely used

vaccines to be made in Africa within 20 years, and agreements were

signed with international organizations representing companies and

donor agencies. But achieving this goal will need some hard

conversations in the weeks and months ahead.

One such conversation must be on the need for sustained and long-term

investment, especially in domestic R&D, as a vaccines industry cannot

be created without this. In spite of the best efforts of researchers

such as the late Calestous Juma, who founded the African Centre for

Technology Studies in Nairobi, most governments, for a variety of

reasons, pushed back against the idea that domestic R&D is of long-

term value. It needed a pandemic to persuade Africa’s leaders to be

convinced of the case for bigger investments. That is to be welcomed

— but it will need more than warm words at a conference to provide

assurance that the plans being hatched will come to fruition.

There will also need to be hard conversations with donor countries,

their pharmaceutical companies, and funders and researchers —

essentially, all those currently involved in supplying Africa with

vaccines. If the goal is now African self-sufficiency in what some

call the vaccine ‘value chain’, then international partnerships with

the continent’s institutions will require a different approach. A

partnership in which the objective is to empower the continent’s own

researchers and businesses will need to be different from existing

partnerships, in which the objective is to supply Africa with

vaccines. Some international companies might regard African self-

sufficiency as a long-term risk to their business; some might fear a

loss of influence. Firms and researchers from outside Africa

shouldn’t take this view if they agree that a genuine partnership of

equals is in everyone’s interests. Vaccines are essential to public

health. And public health is essential to strong economies.

. . .

The world’s researchers have created, and continue to create,

innovative vaccines. But it is now time to grow and share this

knowledge with colleagues in under-served regions, especially in

Africa. Their intervention in Africa’s vaccine-manufacturing

ambitions might well be too late to make a difference during the

present pandemic, but it will almost certainly help to ensure that

the continent’s people are much better protected during the next.

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication

providing reposted commentary and analysis on African issues, with

a particular focus on U.S. and international policies. AfricaFocus

Bulletin is edited by William Minter. For an archive of previous Bulletins,

see http://www.africafocus.org,

Current links to books on AfricaFocus go to the non-profit bookshop.org, which supports independent bookshores and also provides commissions to affiliates such as AfricaFocus.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please

write to this address to suggest material for inclusion. For more

information about reposted material, please contact directly the

original source mentioned. To subscribe to receive future bulletins by email,

click here.

|