|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

Mozambique/Global: War, Intervention, and Solidarity

AfricaFocus Bulletin

May 31, 2021 (2021-05-31)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

“No amount of international military assistance will, within two years, create a fighting force that can combat the insurgency. Two other factors complicate external support. Foreign intervention is likely to provoke a response from Islamic State to provide weapons and training to the insurgents. And the fight is already underway between factions in Frelimo over the upcoming 2024 elections. Cabo Delgado politics and economics, the police and military, and the war itself are already caught up in the bitter infighting. Thus the war seems likely to escalate and continue until a new president is in place in 2025.” - Joseph Hanlon

Long-time subscribers to AfricaFocus Bulletin will know that I occasionally publish two Bulletins on one day (although not more than 4 times a year). This Bulletin (available at http://www.africafocus.org/docs21/moz2105a.php) and its companion Bulletin on Mozambique/Global: Fossil Fuels, Debt, and Corruption (http://www.africafocus.org/docs21/moz2105b.php) are the first such double-posting this year. The reasons are both personal and analytical, given my editorial criterion of focusing on developments relevant for the entire continent and for the world, as well as one particular country. This editorial note is also longer than usual, although even so it points to more questions than answers.

First, it's personal for me, since Mozambique has been the African

country to which I have had the most personal ties for more than 50

years, since first arriving in Dar es Salaam to teach at the FRELIMO

secondary school in 1966. My time actually living and working with

Mozambicans, first in Tanzania and then in Mozambique and working

with Mozambicans only amounts to five years in the 1960s and 1970s.

And my occasional visits for research or conferences in the decades

since then have been far less frequent than I would have wished. But

like my Mozambican friends and others who have worked in that

country, I am acutely and painfully aware that Mozambique is now

suffering its third war over the last six decades.

All three have been the result of complex interactions of national,

regional, and global factors. The armed struggle for independence

lasted 10 years, from 1964 to the 1974 agreement for transition to

independence in 1975. The post-independence war from 1976 to the

peace agreement in 1992 was simultaneously a regional war fueled by

Rhodesia and South Africa and an internal conflict. And the present

“insurgency” in the northeastern province of Cabo Delgado is driven

both by internal discontent and by a mix of external factors. It

began in October 2017 and has escalated sharply since March 2020,

drawing increased international news coverage and debate.

But much of that coverage is superficial and focused on the single

issue of whether external actors should intervene militarily or not,

and if not, which of the numerous candidates to do so should step up

first. Within Mozambique and the Southern African region, there is a

much better informed debate by both scholars, civil society

activists, and in the media about the causes of the conflict and

what kind of response is needed from Africa and the global

international community, prioritizing humanitarian assistance and

development rather than a military solution.

[Those who know me will know that I am normally not a fan of webinars, which often supply less solid content than the time they take to watch. But this 2-hour webinar hosted by SAPES Trust on May 27 (https://www.facebook.com/sapestrust/videos/1076962609494070) is an exception. These are real experts from Mozambique and the region with in-depth knowledge of the issues engaged in real debate. No answers, but keen insights and eloquent presentations. A must-watch for anyone wanting to understand the real options for international response to the conflict and humanitarian crisis in Cabo Delgado.]

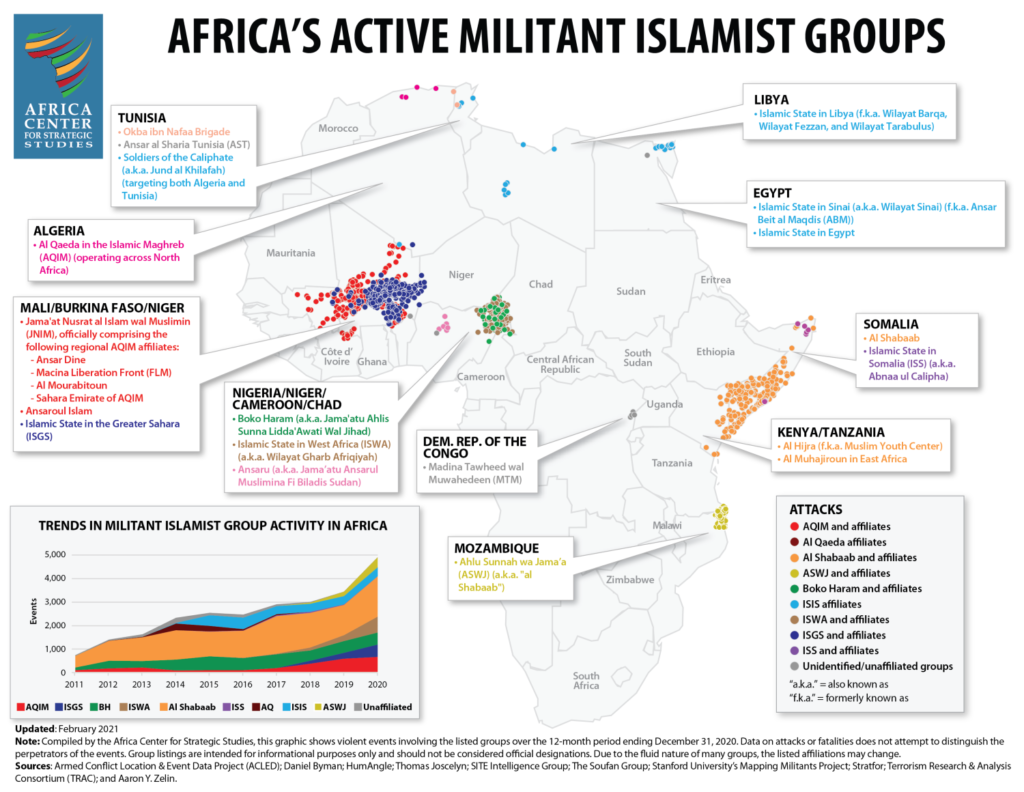

Mozambique's Cabo Delgado is now a central test case for whether

lessons have been learned from the consistent failures of such a

military solution in Mali, Somalia, and northeastern Nigeria. Sadly,

it is likely to be a protracted repetition of such mistakes, with

the added complexity of the interests of multinational natural gas

companies.

This AfricaFocus Bulletin contains excerpts on the war in Cabo Delgado from recent newsletters by Joseph Hanlon. The situation is rapidly changing, but Hanlon regularly provides updates, links to other sources in English and Portuguese, and well-informed analysis. You can subscribe to his newsletter at https://bit.ly/Moz-sub.

My apologies for the length of this comment and of these two

Bulletins. If you do not have time to read them now, I hope that you

will put them aside for later reference. For now, however, I have

several suggestions.

- Do read and watch this first short on-the-scene report from the conflict zone in Cabo Delgado, from May 27, 2021, by veteran BBC journalist Catherine Byaruhanga, who is based in Uganda (https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-57254543).

"Today, on one of the islands - Quirimba - rows of white tarpaulin tents line the white sandy beaches. We are the first international journalists to arrive here since the attack on Palma. More than 9,000 people from different parts of Cabo Delgado are seeking shelter here.

Thirty-two-year-old Mamo Sufo from Palma and her three young children arrived at the island just days before we did.

By this point, it was nearly two months since the town was overrun but she's spent all that time travelling to Quitunda and other villages before taking a boat to Quirimba where she hopes other family members will join her.

She started her journey seven months pregnant, but while out at sea she went into pre-term labour and her son died." - Catherine Byaruhanga

- Do read this summary of the report on the hidden debts, from the Mozambique News Agency, May 29, 2021 (https://allafrica.com/stories/202105290201.html), and

- Take a break from the news by watching the short music video embedded at the end of this Bulletin (a new feature I added last week, featuring videos I have found it essential to watch while taking breaks from writing subjects which more often feature grim realities than hope for change. The videos I choose are not linked to the specific theme of each Bulletin, but they definitely illustrate the visions of the resilience and hope needed both by Africa and the world.)

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on Mozambique, visit http://www.africafocus.org/country/mozambique.php

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on peace and conflict in Africa, visit http://www.africafocus.org/intro-peace.php

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

Mozambique: News Reports and Clippings

545 - part 1 - 16 May 2021

Editor: Joseph Hanlon ( j.hanlon@open.ac.uk)

To subscribe or unsubscribe: https://bit.ly/Moz-sub

Articles may be freely reprinted but please cite the source.

This newsletter in pdf is on http://bit.ly/Moz-545-gas

Part 1 - security

Security will be at the top of the agenda when President Filipe

Nyusi meets French President Emmanuel Macron on Tuesday (18 May) in

Paris. Also in Paris will be Antonio Costa, who is both Portuguese

Prime Minister and President of the Council of the European Union

(EU), and he will probably also meet with Nyusi. But their agendas

will be very different. Macron wants Nyusi to agree on a French

security cordon so Total can return to Afungi. Costa wants

Portuguese soldiers in Mozambique, preferably under an EU umbrella.

Total's declaration of force majeure and its complete

withdrawal from Afungi means it does not expect to return soon -

definitely not this year. But it has to return within two years.

Longer than that will require renegotiating contracts - with buyers,

contractors and the Mozambique government, And a delay in production

to 2026 or 2027 will require rethinking about whether or not there

is a long term market for gas (discussed in part 2 of this special

report).

What Total decides determines what happened to the other large

gas block (area 4), which is run by Exxon Mobil (with a 28% stake).

Exxon has repeatedly delayed it final investment decision, now

pushed back to 2023, and will not agree before Total is back at

work. Area 4 has China's only gas investment in Mozambique; China

National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) has a 12% stake. The

newsletter China-Lusophone Brief (30 Mar) says this

investment in now imperilled. So what happens in the next two years

determines the future of not just Total, but Exxon and its partners

as well.

No amount of international military assistance will, within two

years, create a fighting force that can combat the insurgency. Two

other factors complicate external support. Foreign intervention is

likely to provoke a response from Islamic State to provide weapons

and training to the insurgents. And the fight is already underway

between factions in Frelimo over the upcoming 2024 elections. Cabo

Delgado politics and economics, the police and military, and the war

itself are already caught up in the bitter infighting. Thus the war

seems likely to escalate and continue until a new president is in

place in 2025.

After being misled by President Nyusi in March about the ability

of the Mozambican defence forces to protect Palma and Afungi, Macron

will probably tell Nyusi that Total will only return if France has

complete control of a large security zone. This will be hard for

Frelimo to swallow and there will be delay, but they want the gas

money and will eventually agree - especially if there is another

successful attack on Palma.

. . .

Multiple foreign players

With Mozambique's defence forces (FDS) weak, divided and corrupt -

and now at the centre of high level fights inside Frelimo - the FDS

has little chance of winning a purely military war against guerrilla

insurgents. That leaves two alternatives. One way is to resolve the

grievances that are at the root of the war, sharing the resource

wealth and creating thousands of jobs. That is unacceptable, because

so many people are profiting, and because if Mozambique admits the

cause of war is poverty and inequality, it is effectively admitting

responsibility. The alternative route is to blame external

aggression by Islamic State (IS) and call on outsiders to join the

new holy war against IS. And this is the route that Frelimo has

chosen.

Four countries and two international bodies have shown some

interest in joining the war: the United States, Portugal, South

Africa and Rwanda, as well as the Southern African Development

Community (SADC) and the EU. Because of Total, France is also a

possible player, although it might prefer to stick to its security

zone.

Portugal is sending an 140-person training

mission of whom 60 are already in Mozambique, training marines in

KaTembe and commandos in Chimoio.?Training will continue for three

years. Portuguese and Mozambican defence ministers Joao Cravinho and

Jamie Neto met in Lisbon 10 May and signed a five year military

cooperation agreement.

United States (US) A dozen US special force

soldiers completed two months of training of Mozambican marines on 5

May, and another training session will start in July. On 10 March

the US called the insurgents "Islamic State of Iraq and Syria-

Mozambique (ISIS-Mozambique)" and designated them as a "foreign

terrorist organisation". The US said on 6 May that it would provide

humanitarian assistance in response to what the US State Department

called "devastating violence by ISIS-affiliated terrorists".

Rwanda. President Nyusi flew to Rwanda on 28

April and met President Paul Kagame, who promised military help.

Just 10 days later, on 8 May, a Rwandan military mission was seen in

Pemba.

Southern African Development

Community (SADC) sent an assessment mission 15-21 April

which recommended a 3,000-person regional military force plus

submarines, surveillance aircraft and drones. SADC expects the EU

and US to fund the mission. It would take a year or more to get such

a mission on the ground. South African President Cyril Ramaphosa

said on 10 May South Africa would join such a force if asked. But

Mozambique has not encouraged the SADC mission.

The European Union (EU) is divided and slow. The

European Union must move with “urgency” to step up its support for

Mozambique, said Josep Borrell, EU "foreign minister" (High

Representative for Foreign Affairs) on 6 May. But with a hint of

frustration, he continued: “We are considering a potential European

Union training mission, like the ones that we already have in

several African countries.” Borrell said any mission would be

similar to the EU’s involvement in the Sahel. He hoped a mission

could be sent to Mozambique before the end of the year, and

suggested sending 200-300 soldiers to Mozambique. Portugal currently

holds the EU’s six month rotating Council presidency, and has been

pushing for EU involvement in Mozambique. “Portugal has already

offered half of the staff [and] sent in advance military structures.

It will be integrated into the EU training mission, if we finally

agree on that,” said Borrell. But there is no agreement yet.

. . .

Does a military response ignore the roots of war?

The rush for military support has caused substantial debate. Many of the issues were raised in a letter from 30 African civil society organisations (CSOs) to SADC, in response to the proposal to send 3000 troops - a major military force. The CSOs' letter is on http://bit.ly/Moz-CSO-SADC.

It welcomes "collective action from SADC" but continues: "We urge

our leaders to consider the lessons learnt from other similar

conflicts in Africa. Sahel, Somalia, and the Niger Delta offer stark

contemporary reminders that a purely militaristic solution (devoid

of measures to address the causes of the insurgency) increases the

likelihood of its intractability. It is also unlikely to pave the

way towards achieving sustainable peace."

"Any SADC intervention should also provide avenues to pursue

political and diplomatic solutions to the conflict. This

necessitates an acute understanding of the root causes of the

conflict, push and pull factors that lead to the recruitment of

locals and youth into insurgency operations, and the motivations of

actors operating in the region." Creating a sustainable peace

requires creating "avenues for local communities to address their

grievances with government, which is paramount to addressing the

root causes of conflict."

And the CSO letter calls for "holding government and businesses

to the highest levels of accountability regarding their operations

in Cabo Delgado. Corruption, maladministration, and skewed

development are central to communities’ feelings of marginalization.

Ensuring that citizens receive the lion’s share of dividends from

gas revenue form part of broader longer-term socio-economic

solutions to insurgency."

Two key issues are raised by the CSOs' statement, the roots of

the war and danger that foreign military forces will remain

indefinitely.

There is a quite broad agreement that the insurgency was

initially local and based on local grievances about growing poverty,

inequality and marginalisation. The division is about what happened

next. The US argues that the insurgency has been totally taken over

by IS which now commands and controls. But the respected

International Crisis Group say IS does not have "the ability to

exert command and control." Local researchers confirm that although

there is contact with IS, command and control remains local and the

grievances remain important for insurgent recruiting.

The CSOs stress the role of government and business in the

"skewed development", which effectively puts the blame for the war

on Frelimo and government. This suggests that diverting money from

those getting rich on the gas and minerals and instead using the

wealth to create jobs and development would play a key role in

ending the war.

It is also central to the interveners. The US, EU and others

would not support Mozambique to kill hungry, illiterate peasants

demanding a share of the wealth. But they would intervene in a war

against Islamic State.

And Frelimo and the Mozambique government are being very careful

that those who intervene do not talk about grievances and root

causes. Thus it supports intervention by foreign governments and

private military companies, which it can control, and not by

international bodies such as the UN, EU and SADC, which issue

statements it cannot control.

. . .

**************************************************************

Mozambique: News Reports and Clippings

546 - 20 May 2021

This newsletter in pdf is on http://bit.ly/Moz-546

Total will return only with peace and tranquillity

“As soon as Cabo Delgado has peace again, Total will return,” the

president of the French oil and gas company, Patrick Pouyanee,

promised Monday (17 May). President Filipe Nyusi confirmed Tuesday

(18 May) that Total will return only when everything “is calm”.

“Total may demand that there is tranquillity and peace to develop

its economic projects," Nyusi added. (Lusa 18 May)

France has shown “complete willingness” to provide whatever is

necessary for Mozambique’s fight against terrorism in the northern

province of Cabo Delgado, according to President Filipe Nyusi after

his meeting in Paris with his French counterpart, Emmanuel Macron,

on Tuesday. (18 May) Nyusi said “we discussed in detail the

situation of terrorism. The matter is unavoidable. France has shown

great willingness, but it has left sovereignty in the hands of

Mozambicans”. To follow up, Nyusi said, the two countries must

advance quickly to sign the agreements which will define exactly the

type of support to be granted by France. (Mediafax 19 May) But it

remains unclear if Mozambique sovereignty will allow enough of a

French presence to guarantee the tranquillity and peace Total

demands.

Nyusi also met in Paris with Arnaud Pieton, executive

administrator of Technip, the principal offshore contractor. Pieton

said "we have received guarantees from the Mozambique government

that they are doing everything to reintroduce security, and this is

a fundamental condition for the project to be developed rapidly." (

O Pais 19 May)

Government still blocking aid to Palma; the focus on 'terrorists' makes it worse

There is still no aid reaching up to 20,000 people not being allowed to leave Quitunda near Palma. Finally Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) has spoken out. "Significant restrictions are placed on the scale up of the humanitarian response due to the ongoing insecurity, and the bureaucratic hurdles impeding the importation of certain supplies and the issuing of visas for additional humanitarian workers," said Jonathan Whittall, MSF Director of Analysis, on 14 May. http://bit.ly/Moz-Palma-MSF

It is also made very difficult for foreigners to visit the area.

The UN was allowed to send a team to Quitunda on 21 April, but could

not negotiate aid access. After the visit, the International

Organization for Migration (IOM) called "for full humanitarian

access and a reduction of bureaucratic impediments, including the

issuing of visas [for UN experts], to ensure timely and efficient

delivery of humanitarian aid." There is also a need for "greater and

strategic engagement with the Government," said Laura Tomm-Bonde,

IOM's head of mission in Mozambique. But the call fell on deaf ears.

Whittall, too, recently visited but apparently without gaining

access.

He writes: "What does seem set to scale up is the regionally

supported and internationally funded counter-terrorism operation

that could further impact already vulnerable people. In many

conflicts, from Syria to Iraq and Afghanistan, I have seen how

counter-terrorism operations can generate additional humanitarian

needs while limiting the ability of humanitarian workers to respond.

"Firstly, by designating a group as ‘terrorists’, we often see

that the groups in question are pushed further underground - making

dialogue with them for humanitarian access more complex. While

states can claim that they 'don’t negotiate with terrorists',

humanitarian workers are compelled to provide humanitarian aid

impartially and to negotiate with any group that controls territory

or that can harm our patients and staff."

"For Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF), successfully providing

impartial medical care requires reserving a space for dialogue and

building trust in the fact that our presence in a conflict is for

the sole purpose of saving lives and alleviating suffering."

Whittall is showing why the Mozambique government is trying to

keep out the foreign humanitarian workers. The government says that

it cannot find anyone with whom it can negotiate. MSF says it can

"negotiate with any group that controls territory" - and clearly has

in Cabo Delgado.

"Counter-terrorism operations try to bring humanitarian

activities under the full control of the state and the military

coalitions that support them. Aid is denied, facilitated or provided

in order to boost the government’s credibility, to win hearts and

minds for the military intervening, or to punish communities that

are accused of sympathising with an opposition group. The most

vulnerable can often fall through the cracks of such an approach,

which is why organisations like MSF need to be able to work

independently. … Being aligned to a state that is fighting a

counter-terrorism war would reduce our ability to reach the most

vulnerable communities to offer medical care."

"In counter-terrorism wars around the world, we often see

civilian casualties being justified due to the presence of

‘terrorists’ among a civilian population. Entire communities can be

considered as ‘hostile’, leading to a loosening of the rules of

engagement for combat forces," Whittall writes.

And he concludes: "The current focus on ‘terrorism’ clearly

serves the political and economic interests of those intervening in

Mozambique. However, it must not come at the expense of saving lives

and alleviating the immense suffering facing the people of Cabo

Delgado."

548 - 30 May 2021

South Africa says send troops; Tanzania says no troops, instead negotiate, develop

South Africa is pressing for urgent military intervention in Cabo Delgado, South African Foreign Minister Naledi Pandor told Reuters (21 May) in a telephone interview. Since 2008 SADC has had a regional defence pact that allows military intervention to prevent the spread of conflict. "We support the use of the defence pact. It's never been really been utilised in the region, but we believe this is the time, this is a threat to the region," Pandor said.

Tanzania will not send troops to Mozambique to counter insurgents in Cabo Delgado, Minister of Foreign Affairs Liberata Mulamula said Wednesday 26 May in Dar es Salaam. The Tanzania government has, instead, emphasised on the need for talks as a means of promoting peace and tranquility in Mozambique, calling on the international community to help the country by sending development aid. (Citizen 27 May)

A SADC evaluation proposed 3000 troops and equipment including a

submarine. The SADC summit scheduled to discuss this was postponed

from April to 27 May, and the summit simply postponed the issue

until a new summit on 20 June. President Filipe Nyusi's longstanding

opposition to a multi-lateral force and the opposition of some

countries such as Tanzania suggest the SADC force will never happen.

At the Frelimo Central Committee on 22-23 May, President Filipe

Nyusi made clear he wanted foreign troops. But in his closing

speech, he stressed the "concentration on bilateral efforts to

combat terrorism in Cabo Delgado". It is a point he has stressed in

private talks with diplomats for more than a year, that he does not

want international forces - SADC, EU or UN. Instead he wants

agreements with individual governments and the ability to move and

assign foreign troops to particular zones or tasks. SADC or UN

troops would have their own external commanders, but Frelimo will

only accept foreign troops that it controls - which means private

military companies (PMCs) or bilateral arrangements with

governments.

Will Rwandan troops create the Total security zone?

Rwandan troops may play a central role in creating the security

zone around the Palma-Afungi natural gas area. Rwanda has become a

major participant in peacekeeping missions and has had troops or

police in Central African Republic, Mali, Sudan, South Sudan and

other countries. But more three-way discussions will be needed

between France, Rwanda, and Mozambique.

On 28 April Mozambican President Filipe Nyusi flew to Rwanda for

talks with President Paul Kagame. Just 10 days later a

reconnaissance team of Rwandan officers was in Cabo Delgado. Nyusi

and Kagame were in Paris for the French Africa summit 17-18 May;

both met President Emmanuel Macron and Cabo Delgado was discussed.

Last week Marcon was in Rwanda and South Africa to meet their

presidents on 27 and 28 May. Again, Cabo Delgado was discussed,

although not top of the agenda.

France’s acceptance in a report this year that it bore a

responsibility for the 1994 genocide in Rwanda marked a “big step

forward” in repairing relations between the two countries, which are

now on the mend, Kagame said.

After the fiasco of President Nyusi guaranteeing a security zone

including Palma just days before the insurgents took Palma against

little resistance, Total wants more than just promises. It will

demand overall French control of any security zone, and French navy

control of the ocean off of Cabo Delgado. Mozambique will demand

that its soldiers are on the ground, but will accept a foreign

presence. Rwanda fits the bill. For Mozambique, Rwandan troops are

more acceptable than South African soldiers. For France and Total,

Rwandan troops are well trained and experienced, and much more

effective than Mozambican army or police. Improved relations between

France and Rwanda complete the package.

Who will be top dog?

An increasing number of countries want part of the action, and

there is a quiet struggle as to who will be top dog. On the ground

Portugal has 60 soldiers doing training, the US just finished its

first training mission, Rwanda has a military investigation team,

and South Africa has had private military companies and sent in

soldiers to rescue its civilians after the Palma attack. Off shore,

France and South Africa have regular naval patrols and the United

States and India have had less frequent patrols.

French President Emmanuel Macron travelled to Africa and met

Rwandan President Paul Kagame on Thursday 26 May and South African

President Cyril Ramaphosa on Friday, 28 May. In both countries, the

Cabo Delgado war was on the agenda. In South Africa Macron said

France is available to assist the Mozambican military, but only in

the "'context of a political solution". And any help "should be an

African response at the request of Mozambique and coordinated with

the neighbouring countries," he said. The interest of both Rwanda

and South Africa is that France and the EU pay for their

intervention.

Macron particularly stressed that France already has a regional

presence in its island territories of Mayotte and Reunion, and stood

ready to offer naval assistance. "We have frigates and some other

vessels in the region and on a regular basis organise operations. So

we could be available, and very quickly so, if requested," he said.

Meanwhile EU foreign policy head Josep Borrell said on 28 May

that the EU could have a military training mission in Mozambique in

months. "The problem will be to look for capacities. Apart from

Portugal, who else is going to contribute?"

Saudi Arabia is working with SADC to support the Mozambican

military fight the insurgents, Crown Prince Mohamed Bin Salman said

on 20 May. There is a certain irony in this, as many Mozambicans

have been trained in Saudi Arabia in fundamentalist Islam.

The United States is now beefing up the embassy's security

advisory team with the help of private military contractors (PMCs).

A new adviser to head up the counter-terrorism programme will be

provided by one of the Pentagon subcontractors bidding for the

contract, reports Africa Intelligence (28 May), a Paris

based newsletter which backs Paris in its confrontation with

Washington. The US has been strongly critical of the use by

Mozambique of PMCs, despite their being extensively used by the US

in Afghanistan and elsewhere.

Difficult negotiations are ahead as Mozambique desperately tries

to keep support fractured and in pieces it can control, and at least

four countries want to be top dog:

United States: Wants a base in southern Africa and

has long coveted Nacala, with its big airport and deep water port

that would be good for submarines. Mozambique could be its new base

for the war against Islamic State. Mozambique could be the new

Afghanistan or Libya.

France: Wants control of the gas zone but appears

willing to accept Rwandan fighters. But will expect to control

coastal security.

South Africa: Wants to assert itself as the

regional power but has been cutting the military budget, so hoping

the EU will pay.

Portugal: The military of the former colonial power

want to return and prove their ex-colony still needs them. They are

using their position as president of the EU to gain EU backing for

their operation.

None of these four has won a recent war against a guerrilla

insurgency. Frelimo won a guerrilla independence war 47 years ago,

but has never beaten a guerrilla force.

Fighters or job creators?

As governments try to militarise Cabo Delgado, civil society

groups increasingly stress the need to resolve the roots of the war

- growing poverty and inequality, youth seeing no jobs and no

future, and the belief that the Frelimo elite are eating all the

wealth from rubies, gas, and other resources.

Speaking to Reuters, [South African] Foreign Minister Pandor said

“We have had our colleagues, for example in Nigeria, saying: ‘don’t

allow this to get out of hand because once it does it is

uncontrollable and very difficult to reverse’. So, that is why we

believe it is urgently necessary that we have action.” Academic

analysts point to the similarity to the roots of Boko Haram in

Nigeria and al Shabaab in Cabo Delgado. Both are groups in Muslim

areas where young people feel marginalised and with no future, and

they are recruited on that basis. Thus the "don’t allow this to get

out of hand" lesson is the need to create jobs and development

before the war gets out of hand. It is, contrary to Pandor, not

military but development intervention that is urgent.

Three articles from the South African mainstream establishment

point to alternative thinking:

"Suicidal SADC military deployment to Mozambique looms" was the headline of an opinion article in the Johannesburg Business Day (28 May) "SA soldiers will return home in body bags, as was the case in the failed military deployment to the Central African Republic in March 2013. The defence force must serve sovereign national interests and not the interests of private actors working for profit." The article argues that South Africa government is under pressure from national corporations and France to protect the profits of their investors.

The article continues: "Like France and its transnational

corporation Total, the LNG project in Mozambique is critically

important for SA and its corporations. SA state financiers the

Industrial Development corporation (IDC), the Export Credit

Insurance Corporation (ECIC) and the Development Bank of Southern

Africa (DBSA) have, in total, lent more than $1bn in public funds to

the LNG project. Standard Bank has sunk $485m into the project, and

other major players include Absa and Rand Merchant Bank."

The article is written by Sam Hargreaves, director of

WoMin/African Women Activists, and Anabela Lemos of Justica

Ambiental/Friends of the Earth Mozambique. The article's publication

in a mainstream business newspaper suggests opposition to

militarization of Cabo Delgado is gaining a hearing.

"Regional support is a good start, but much more than a SADC military deployment to Mozambique is needed," according to a 27 May report from the Institute of Security Studies (ISS) of South Africa. "At the root of the conflict is a governance challenge that includes allegations of deeply entrenched corruption in the ruling party, Frelimo. Poor governance and state absence have antagonised the local population and left a security vacuum. … The government must commit to the development and effective governance of the region."

Military support may be needed to contain the violence. But the

report stresses "the education system must be reinvigorated to train

and prepare locals for skills suited to new job opportunities.

Authorities in Cabo Delgado would also need to invest in public

works programmes to complement job creation in the formal and

informal sectors and offer social activities such as sport to engage

the youth. An important poverty-alleviation measure would be a cash

transfer (or social grants) programme that would directly benefit

the community and demonstrate the government’s commitment to

development."

"Maputo needs to own and drive the response to the insurgency and

the recovery of local and investor confidence. No amount of private

security advice, support or foreign troops and equipment can

compensate for political leadership and the establishment of trust

between people, the government and regional actors." Lead author of

the report is Jakkie Cilliers, founder and former Executive Director

of ISS - another indication that senior establishment figures are

pointing to the roots of the conflict.

"Regional military intervention in Mozambique is a bad idea," wrote Gilbert M. Khadiagala, Professor of International Relations at the University of the Witwatersrand, on 27 May. He argues "SADC interventions in internal conflicts in its neighbourhood haven’t worked out well." In 1998 Botswana, South Africa and Zimbabwe intervened in Lesotho. "South African troops lost their lives and SADC troops had to withdraw in ignominy. The SADC has since had to continually intervene as a peacemaker in the fractious terrain of Lesotho politics."

The other major intervention was by Malawi, Tanzania and South

Africa to defeat the M23 Movement in the Democratic Republic of

Congo (DRC) in 2013. Initially it made a difference. "But the

militia menace in the region has continued unabated, raising

questions about the long term efficacy of the brigade’s work," notes

Khadiagala.

More generally, military interventions in resource curse civil

wars only make matters worse, he says, citing South Sudan, Cabinda

in Angola, and the Niger Delta.

"SADC is now being asked to intervene in a conflict [in

Mozambique] that it has neither resources nor the political will to

manage. When the body bags begin to come home, there will be

tremendous pressure on SADC forces to withdraw. Rather than the

folly of an intervention, the region should be encouraging the

Mozambican state to address the grievances of the communities in

Cabo Delgado." Khadiagala concludes: "SADC’s military intervention

will only embolden die-hards in Frelimo who are reluctant to find

peaceful and political solutions to the crisis. And the intervention

will postpone a problem that is not going to go away any time soon."

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication

providing reposted commentary and analysis on African issues, with

a particular focus on U.S. and international policies. AfricaFocus

Bulletin is edited by William Minter. For an archive of previous Bulletins,

see http://www.africafocus.org,

Current links to books on AfricaFocus go to the non-profit bookshop.org, which supports independent bookshores and also provides commissions to affiliates such as AfricaFocus.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please

write to this address to suggest material for inclusion. For more

information about reposted material, please contact directly the

original source mentioned. To subscribe to receive future bulletins by email,

click here.

|