|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

Mozambique/Global: Fossil Fuels, Debt, and Corruption

AfricaFocus Bulletin

May 31, 2021 (2021-05-31)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

“The scandal of Mozambique’s “hidden debts” has already cost the

country at least 11 billion US dollars, and has plunged an

additional two million people into poverty, according to a detailed

study of the costs and consequences of the debt published on Friday

by the anti-corruption NGO, the Centre for Public Integrity (CIP),

and its Norwegian partner, the Christian Michelsen Institute. The

term “hidden debts” refers to illicit loans of over two billion US

dollars from the banks Credit Suisse and VTB of Russia in 2013 and

2014 to three fraudulent, security–linked Mozambican companies –

Proindicus, Ematum (Mozambique Tuna Company), and MAM (Mozambique

Asset Management).” - report by Centre for Public Integrity

(Mozambique) and Christian Michelsen Institute (Norway)

Long-time subscribers to AfricaFocus Bulletin will know that I occasionally publish two Bulletins on one day (although not more than 4 times a year). This Bulletin (available at http://www.africafocus.org/docs21/moz2105b.php) and its companion Bulletin on Mozambique/Global: War, Intervention, and Solidarity (http://www.africafocus.org/docs21/moz2105a.php) are the first such double-posting this year. The reasons are both personal and analytical, given my editorial criterion of focusing on developments relevant for the entire continent and for the world, as well as one particular country. This editorial note is also longer than usual, although even so it points to more questions than answers.

First, it's personal for me, since Mozambique has been the African

country to which I have had the most personal ties for more than 50

years, since first arriving in Dar es Salaam to teach at the FRELIMO

secondary school in 1966. My time actually living and working with

Mozambicans, first in Tanzania and then in Mozambique and working

with Mozambicans only amounts to five years in the 1960s and 1970s.

And my occasional visits for research or conferences in the decades

since then have been far less frequent than I would have wished. But

like my Mozambican friends and others who have worked in that

country, I am acutely and painfully aware that Mozambique is now

suffering its third war over the last six decades.

All three have been the result of complex interactions of national,

regional, and global factors. The armed struggle for independence

lasted 10 years, from 1964 to the 1974 agreement for transition to

independence in 1975. The post-independence war from 1976 to the

peace agreement in 1992 was simultaneously a regional war fueled by

Rhodesia and South Africa and an internal conflict. And the present

“insurgency” in the northeastern province of Cabo Delgado is driven

both by internal discontent and by a mix of external factors. It

began in October 2017 and has escalated sharply since March 2020,

drawing increased international news coverage and debate.

But much of that coverage is superficial and focused on the single

issue of whether external actors should intervene militarily or not,

and if not, which of the numerous candidates to do so should step up

first. Within Mozambique and the Southern African region, there is a

much better informed debate by both scholars, civil society

activists, and in the media about the causes of the conflict and

what kind of response is needed from Africa and the global

international community, prioritizing humanitarian assistance and

development rather than a military solution.

[Those who know me will know that I am normally not a fan of webinars, which often supply less solid content than the time they take to watch. But this 2-hour webinar hosted by SAPES Trust on May 27 (https://www.facebook.com/sapestrust/videos/1076962609494070) is an exception. These are real experts from Mozambique and the region with in-depth knowledge of the issues engaged in real debate. No answers, but keen insights and eloquent presentations. A must-watch for anyone wanting to understand the real options for international response to the conflict and humanitarian crisis in Cabo Delgado.]

Mozambique's Cabo Delgado is now a central test case for whether

lessons have been learned from the consistent failures of such a

military solution in Mali, Somalia, and northeastern Nigeria. Sadly,

it is likely to be a protracted repetition of such mistakes, with

the added complexity of the interests of multinational natural gas

companies.

This AfricaFocus Bulletin contains excerpts from the new report quoted above on the hidden debt in Mozambique, as well as some additional reflectino by Joseph Hanlon on the future of natural gas in Mozambique. The situation is rapidly changing, but Hanlon regularly provides updates, links to other sources in English and Portuguese, and well-informed analysis. You can subscribe to his newsletter at https://bit.ly/Moz-sub.

My apologies for the length of this comment and of these two

Bulletins. If you do not have time to read them now, I hope that you

will put them aside for later reference. For now, however, I have

several suggestions.

- Do read and watch this first short on-the-scene report from the conflict zone in Cabo Delgado by veteran BBC journalist Catherine Byaruhanga, who is based in Uganda (https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-57254543), from on May 27, 2021

- Do read this summary of the report on the hidden debts, from the Mozambique News Agency, May 29, 2021 (https://allafrica.com/stories/202105290201.html), and

- Take a break from the news by watching the short music video embedded at the end of this Bulletin (a new feature I added last week, featuring videos I have found it essential to watch while taking breaks from writing subjects which more often feature grim realities than hope for change. The videos I choose are not linked to the specific theme of each Bulletin, but they definitely illustrate the visions of the resilience and hope needed both by Africa and the world.)

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on Mozambique, visit http://www.africafocus.org/country/mozambique.php

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on peace and conflict in Africa, visit http://www.africafocus.org/intro-peace.php

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

Costs And Consequences of The Hidden Debt Scandal of Mozambique

Centro de Integridade Pública (CIP), Moçambique, and

Chr. Michelsen Institute, Norway

May 27, 2021

[Excerpts below from the executive summary and the preface.

For the full report in English:

https://www.cipmoz.org/en/2021/05/27/costs-and-consequences-of-the-hidden-debt-scandal-of-mozambique/

Additional coverage from CIP, in both English and Portuguese

https://www.cipmoz.org/en/category/dividas-ocultas/]

Executive Summary

How a $2 billion hidden and corrupt loan has cost $11 billion and

increased poverty

In 2013, bankers in Europe, businesspeople based in the Middle East,

and senior politicians and public servants in Mozambique conspired

to organise a USD 2 billion loan to Mozambique – an incredible 12%

of GDP of one of the poorest countries in the world. The loan was

kept hidden. None of the borrowed money, except bribes, went to

Mozambique, and there were no services or products of benefit to the

Mozambican people.

The knock-on effects of such a huge corruption scandal may already

have cost Mozambique at least USD 11 billion – nearly the country’s

entire 2016 GDP – and almost 2 million people have been pushed into

poverty. If Mozambique is forced to service this debt, there is USD

4 billion more to pay, on top of future damaging impacts.

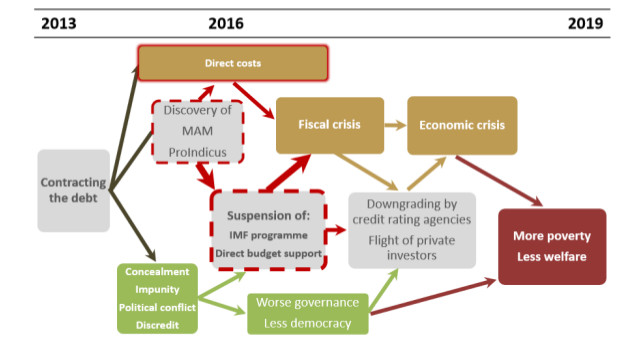

This report is an inventory of the huge costs and consequences of

the hidden debt scandal – measuring them in numbers where possible

and tracing the chain of harmful events and tendencies resulting

from it. The impacts were economic (direct costs and damages),

social (reducing welfare), and institutional (worsening politico-

institutional environment).

Economic costs

There are direct costs associated with the loans, mainly past and

future costs of interest and repayments. Past direct costs – those

incurred up to, and including, 2019 – amounted to USD 674,2 million.

To that will be added another USD 3,93 billion that the country will

have to pay to service the hidden debt until 2031.

The economic crisis was caused partly by the debt itself, but even

more by the damage that flowed from the secrecy and corruption, and

the following discredit. And its impact on Mozambicans was hugely

more than the hidden debt. When rumours about hidden loans began to

circulate, Mozambican ministers lied to the IMF and ambassadors of

Mozambique’s development partners, denying the existence of any

loans. When the Wall Street Journal revealed the hidden debt in

April 2016, the anger was extreme. Donors and lenders had kept the

country afloat, and they pulled the plug.

The IMF halted its programme and donors cancelled direct budget

support and other aid to the government – a reduction of USD 831

million in 2016 compared to the year before. The cascade that

followed included a fiscal crisis making the government unable to

pay its bills, there was a major currency devaluation, foreign debt

became unpayable, the economy slowed down sharply, real GDP per

capita fell, unemployment soared, and poverty increased.

This report calculates that damage. The best and simplest overall

measure of it is the fall in the value of the GDP caused by the

debt, which we calculate to be USD 10.7 billion in the four-year

period. Future costs of lost GDP will continue to pile up, since the

damage caused by the HDS is perennial.

[see table by year in full report]

Summarised, a group of corrupt businesspeople and senior government

officials committed Mozambique to a debt of over USD 2 billion and

split the proceeds of the fraud. That cost Mozambicans, in the years

2016-2019 alone, over USD 11 billion – or USD 403 per citizen.

On top of that, in the decade to come, Mozambique is scheduled to

pay nearly USD 4 billion more in direct costs, plus the incalculable

economic damage.

Social Costs

The sudden reduction of external donations after the hidden loans

were revealed in April 2016 triggered a fiscal and monetary

instability that forced the government to reduce public spending

severely.

In 2016 real public expenditure (in USD) was cut to less than half

of what it was in 2014. That reduction in public expenditure hit the

sectors aiming at social welfare. Comparing the three-year average

of 2016-18 to the three previous years, spending on health and

education fell by USD 1,7 billion – entirely due to the debt. Put in

per capita terms, the scandal caused, for each Mozambican citizen:

- USD 10 less in the education sector, each year

- USD 7 less in the health sector, each year

There are many indications that poverty increased during the years

after 2015, in various ways of measuring it. The sudden rise in

inflation in 2016 and rising prices drove 2,6 million people under

the threshold of consumption-based poverty, as shown by studies

projecting poverty levels in 2016 using data from the most recent

household surveys (IOF 2014/15). We then estimated the proportion of

the increase in poverty to be explained by the hidden debt, and

found that:

- because of the hidden debt scandal, at least 1,9 million people

fell below the line of consumption-based poverty by 2019.

There is no starker measure of the tragedy that the hidden debt

scandal has inflicted upon Mozambicans.

Political and institutional costs

The costs and consequences of the hidden debt scandal on the

political and institutional landscape in Mozambique were real and

severe, yet no single figure or currency captures its full impact.

Mozambique’s performance deteriorated on all relevant indexes

measuring aspects of democracy, governance, public financial

management and credibility in the decade between 2010-2020. Many of

them also registered an acceleration of the deterioration after 2013

when the debt was incurred, and a particularly sharp fall coalescing

with the discovery of the secret debt in 2016 – the “smoking gun”

evidencing the secret debt’s contribution to the deterioration. This

report goes beyond circumstantial evidence and also shows how and

why the hidden debt contributed to the deterioration of governance.

Knowing that the debt was illegal and fraudulent, some powerful

Mozambicans pushed developments contradicting good and democratic

governance. They acted to:

• Cover up the deal and the debt, reducing transparency. Senior

politicians lied to the public about the debt, and public finance

management reforms stagnated or were reversed.

• Seek impunity, manipulating politics and institutions to avoid

accountability for punishable offences. So far, no one in Mozambique

has been held to account and convicted for manifestly illegal

actions. Checks and balances failed. The Justice system and the

Assembly of the Republic were unable to control the actions of the

Executive. A Special commission of the Assembly of the Republic was

highly critical, but no action was taken. The Constitutional Council

ruled that the hidden loans were unconstitutional, but the Executive

has ignored this.

• Create political conflict, reducing institutional cooperation.

Injection of large amounts of money into one faction of the

political elite, and the inevitable bickering over responsibility

following the fraud, increased factional fights and institutional

chaos.

• Discredit the country and its reputation, as the eventual and

inevitable discovery of the debt damaged the Government’s and

country’s reputation and integrity. Mozambique’s credit rating

plummeted, and its reputation as a serious development partner was

severely dented.

Some were inevitable costs of the decision to defraud the state and

the population. However, some political choices were not inevitable.

When Mozambican society reacted to the fraud with demands of

accountability and refusal to pay the debt, the state chose to

implement: authoritarian measures, countering the principles of the

liberal-democratic Constitution. Harassment of key individuals

reduced the scope for public criticism. Blatant manipulation of

elections in 2018 and 2019 reduced chances that the regime would

lose power.

Summarised, the hidden debt and ensuing scandal impacted heavily on

politics and institutions and led to:

1. More contradictions and debilitating conflicts within the state and political system.

2. Worse governance quality and weakened state institutions.

3. Disrepute of the regime and government.

4. A less democratic and more authoritarian country.

Preface

. . .

The hidden debts, the pandemic and other disasters

The final draft of the report was drawn up in the second half of

2020, a time when the Covid-19 pandemic was battering both

Mozambique and the rest of the world. This analysis will make no

mention of this plague, for the simple reason that the last year

included in the report is 2019. It is, however, noteworthy that is

in that year Mozambique suffered the abnormal consequences and costs

associated with the damage caused by the cyclones named Idai and

Kenneth. The consequences of these disasters will be included in the

due analyses under the relevant indicators.

The reader will have the opportunity to understand that a small

group of people linked to the hidden debts scandal, some of them

Mozambican and others foreign, caused damage which greatly exceeds

the losses caused by the cyclones. The debts which they managed to

conceal until 2016 resulted in an economic meltdown, a weakening of

the institutions of governance, and a loss of political and

international trust. They contributed to a worsening of the social

indicators.

While we do not yet know the consequences of the pandemic currently

under way, we are sure that Mozambique would have had much greater

capacity to face the pandemic – and perhaps also the growing problem

of the war in Cabo Delgado – had it not been for the hidden debts.

For example, we will show that it is likely that, without the hidden

debts, the health services would have been in better condition.

Although our analysis is mostly retrospective, it is obvious to us

that the costs of the hidden debts will have consequences of

delaying development, also in the future – like a coefficient that

multiplies the weight of all the other difficulties.

The analysis in the report leaves aside speculations about the

future, the forensic debate about the individuals responsible, and

the politico-normative considerations about the necessary reforms in

governance. It is dedicated mainly to describing and analysing the

consequences of the hidden debts, and calculating their costs

realistically, from their conception up to the end of 2019.

The judicial situation of the HD

When the CIP and CMI team of researchers finished writing this report, 17 citizens were under arrest in Mozambique, accused by the Attorney-General’s Office of being involved and of having benefitted directly from this corrupt scheme. Among them there stand out:

* Ndambi Armando Guebuza, son of the former President of Mozambique, Armando Guebuza;

* Gregório Leão, former director of the State Intelligence and Security Services (SISE) ;

* António Carlos do Rosário, former Chairperson of the Board of Directors of Ematum, ProIndicus and MAM;

* Inês Moiane, private secretary of President Armando Guebuza;

* Renato Matusse, political advisor to the then President Armando Guebuza;

* Teofilo Nhangumele, one of the Mozambicans who is also accused in this same case by United States prosecutors.

Internationally, the former Minister of Finance, Manuel Chang, has

been under detention in South Africa since 29 December 2018,

awaiting a decision as to whether he will be extradited to the

United States or to Mozambique. While Chang was awaiting this

decision, in the United States, in a New York court, Privinvest

official Jean Boustani was tried and the jury considered he had not

committed the crimes of which he was accused within the New York

jurisdiction, and so he was acquitted.

In London courts, other lawsuits are under way. In one of them, the

Mozambican Attorney-General’s Office is pitted against the bank

Credit Suisse and Privinvest, while in others a group of creditors

is fighting the Mozambican government, as well as VTB against MAM

and the Republic of Mozambique.

So, when the final draft of this report was produced, this case was

still far from reaching an outcome in the various jurisdictions

where the lawsuits were being waged. However, its effects, as from

2016, are already visible in the lives of millions of Mozambicans

who have witnessed a worsening cost of living and the deep economic

and financial crisis into which the country has been plunged. With

regard to the lawsuits, although it is regrettable, the delay in the

trial of the various cases related with this enormous corruption

scheme is understandable. It is justified by the fact that the cases

are taking place in several jurisdictions and may potentially have a

contagion effect – that is, the decision in one case may influence

or produce evidence for the other cases.

The path to follow

However, the same excuse cannot be used for the delay in introducing

structural reforms to prevent the occurrence of new scandals on this

scale. Since the discovery of the hidden debts, in April 2016, more

than four years have passed and the focus of the analyses is still

on the individuals who were behind the contracting of the debts, and

never on analysing how the system of checks and balances completely

failed to create antibodies so that a fraud of this nature would not

happen .

The Assembly of the Republic (AR) failed completely in its role of

checking the actions of the Executive, and did not redeem itself

even after the debts were discovered. The parliamentary commission

that investigated the case was a clear example of this failure of

the AR. The Mozambican parliament never managed to take the case of

the hidden debts as an opportunity to initiate a more profound

debate on the role of the legislature as inspector of government

actions, probably because parliament is controlled by the ruling

party which benefitted from the swindle (in the New York court,

documents were presented which proved bank transfers of about USD 10

million to finance the party’s campaign), in which at least part of

the leadership was complicit. So, it is an inconvenient matter for

the Frelimo parliamentary group.

As for the judiciary, this also showed it did not have enough power

to force the Executive to comply with the Constitution. The refusal

of the government to obey rulings of the Constitutional Council is

the most flagrant example.

It is essential that the country should reflect deeply on the

structural reforms that should be implemented so that cases like

this are not repeated. And after this reflection, mechanisms must be

set up to guarantee that these reforms are undertaken. The Assembly

of the Republic should lead this process.

But intellectuals, academics, civil society organisations and the

public in general can and should play an important role in helping

the political institutions make the necessary reforms. Currently,

the weaknesses of the system persist. Hence, new actors and the

knowledge of what went wrong with the hidden debts, could lead to an

even more daring swindle, and one which avoids financing from

western countries, such as the United States and Britain who have

legislation which can act belong their physical borders.

If the internal control systems remain weak, if the parliament and

the judiciary remain decorative bodies, then the Government of the

day, under a presidentialist system in which the President of the

Republic is all-powerful, can seek financing from creditors who are

outside of the western financial systems, but who have liquidity

and as a counterpart for the high risks involved, demand in

exchange the country’s natural resources.

The institutional weakness, the weakness of the institutions that

should act as checks and balances raises some questions in the event

that Mozambique manages to win the lawsuits that it brought in

London, and if it has to be compensated for the damage done to

Mozambicans. If this hypothesis comes to pass, where would the money

paid to the country in compensation for the damage caused by the HD

go? If the institutions are not credible and controlled by the

Executive and by the party that controls the government, it raises

the possibility of this money returning to the hands of some of

those involved in this case, thus overturning all the efforts that

are being made so that companies such as Privinvest, Credit Suisse

can be held responsible for the damage done to the country.

This report is a contribution to the debate around this matter and

may be a useful tool for political decision makers, for public

institutions, for the Assembly of the Republic, the Attorney-

General’s Office, the Administrative Court, the Constitutional

Council, the private sector, civil society organisations,

intellectuals, academics, and the public at large.

We are confident that the report will contribute to constructive and

structuring debates. Debate it, criticise it and improve its

analyses and estimates! But, above all – use it! Let the extent and

gravity of the injustice committed be known, so that it is never

repeated, and so that its lessons may be used to build a more just,

equitable and safe society!

Edson Cortez

Executive Director of CIP

May, 2021

*******************************************************

Mozambique 546 - Energy agency says no more Moz gas; Total demands peace - 20 May 2021

International Energy Agency says no future for Mozambique gas

This newsletter in pdf is on http://bit.ly/Moz-546

Mozambique's gas fields cannot be developed if global warming is to

be kept to 1.5º above pre-industrial levels, according to a dramatic

International Energy Agency (IEA) report published Tuesday (18 May).

The IEA is part of OECD and thus represents establishment,

mainstream thinking. So when it says gas is done, that carries

significant weight.

The IEA report is entitled Net Zero by 2050, and shows what needs to be done to reduce global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions to net zero by 2050, to limit the long-term increase in average global temperatures to 1.5º C, and ensure universal access to electricity and clean cooking by 2030. https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-by-2050

To do this requires that "beyond projects already committed as of

2021, there are no new oil and gas fields approved for development."

Only two Cabo Delgado projects fit within that window - ENI's

floating LNG plant (3 million tonnes per year - mt/y - of LNG) and

Total's suspended project (13 mt/y). ExxonMobil has still not

committed, and Total has not committed to a larger project, so under

IEA scenario they are excluded. In any case, the Economist

(4 Feb) reports that shareholders are pushing ExxonMobil to go

green. This means production of at most 16 mt/y, which is far less

than the 100 mt/y being predicted just six years ago.

"The contraction of oil and natural gas production will have far-

reaching implications for all the countries and companies that

produce these fuels. No new oil and natural gas fields are needed."

This will mean a huge cut in projected income for gas-producing

countries. "Net zero calls for nothing less than a complete

transformation of how we produce, transport and consume energy."

"No new natural gas fields are needed… beyond those already under

development. Also not needed are many of the liquefied natural gas

(LNG) liquefaction facilities currently under construction or at the

planning stage. Between 2020 and 2050, natural gas traded as LNG

falls by 60%. ... In the 2030s some [gas] fields may be closed

prematurely or shut temporarily."

. . .

Global 2º compared to 1.5º for Mozambique: Hotter, drier, worse

cyclones; south hit hardest

IEA cites extensively a report by the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel

on Climate Change), which is so detailed that it is possible to

estimate the difference between global warming of 1.5º and 2º for

Mozambique. The 1.5º and 2º are global average increases, and the

actual impacts vary significantly across the world, and even within

Mozambique.

+ Temperature rise in Mozambique will be more serious at global 2º

than global 1.5º of warming. The hottest days and coldest nights

will both be hotter. Global 1.5º causes a Mozambique temperature

rise, but the increase is much greater at 2º. The number of hot days

increases more in the north than in the south.

+ Southern Mozambique will become much dryer at 2º with droughts.

Water shortages will be more severe at 2º than 1.5º. The number of

consecutive dry days increases, particularly in the south.

+ Total rainfall will decrease more at 2º than 1.5º across

Mozambique, and will be most serious south of the Zambeze river.

However extreme rainfall increases significantly, particularly in

northern coastal zones.

+ The number of cyclones may actually decrease, but their intensity

increases. Thus flooding causes by heavy rain and intense cyclones

will be more serious with 2º warming than with 1.5º.

+ The ocean will get warmer, and sea level will rise - with

significant difference between 1.5º and 2º.

+ There is increased

risk to mangroves.

+ Moving from 1.5° to 2° of warming reduces maize yield and the suitability of maize as a food crop. Food shortages are predicted, and the risks at 2º are "much larger than the corresponding risks at 1.5°".

This all comes from an extremely detailed comparison of 1.5º and 2º with maps good enough to identify differences within Mozambique in Chapter 3 of the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) thick 2018 tome Global warming of 1.5ºC https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/ .

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication

providing reposted commentary and analysis on African issues, with

a particular focus on U.S. and international policies. AfricaFocus

Bulletin is edited by William Minter. For an archive of previous Bulletins,

see http://www.africafocus.org,

Current links to books on AfricaFocus go to the non-profit bookshop.org, which supports independent bookshores and also provides commissions to affiliates such as AfricaFocus.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please

write to this address to suggest material for inclusion. For more

information about reposted material, please contact directly the

original source mentioned. To subscribe to receive future bulletins by email,

click here.

|