|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

Sahel: Questioning Counterterrorism?

AfricaFocus Bulletin

March 22, 2021 (2021-03-22)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

“In the context of complex and protracted conflicts, it is time to

rethink the role of the international community and acknowledge its

limits. Today, success depends first and foremost on the willingness

(much more than on the capacity) of corrupt leaders to reform and

renew their social contract with citizens, especially in rural areas.

International efforts will fail as long as impunity prevails and

local armies can kill civilians and topple governments without

consequence.” - Chatham House Research Paper

The critique is not new (see, for example, earlier reports in Africafocus in 2017, 2009, and 2007). What is new is that the critique now seems to be the consensus in elite Western policy circles, as reflected in the report cited and excerpted below from Chatham House in London and two very similar analyses from CSIS in Washington and the International Crisis Group in Brussels.

All seem to agree that Western counterterrorism policy in the Sahel

has been both over-militarized and ineffective. All suggest, in

slightly varying language, that policy must be “rebalanced” or

“rethought” to emphasize governance and diplomacy, including “talking

with terrorists.” The emphasis on governance as well as military

action has long been part of the rhetoric of the international

community and of the powers most engaged in the region. But the tone

is now clearly different and the recognition of the failures to date

is widespread.

Unfortunately, it seems likely that the policy in practice is still

unlikely to follow the rhetoric, as the institutions invested in

military solutions have far more influence due to their bureaucratic

weight and untested assumptions such as that military success must

come first. Attention to the realities of national governments and

local communities is sporadic and inconsistent in contrast to

globally reinforced counterterrorism dogma. And there are strong

incentives for policy makers to resist the realization that their

military action is not only ineffective but in fact often accelerates

violence.

This is now painfully being illustrated across the continent, as the United States and other Western powers are moving to provide new military support for Mozambican government forces in Northern Mozambique fighting against a brutal Islamist insurgency there. This comes against the advice of virtually all knowledgeable about the conflict (see new reports last week in the New York Times and in the well-informed newsletter on Mozambique edited and published by Joseph Hanlon).

In addition to excerpts from the Chatham House report on the Sahel,

this AfricaFocus Bulletin contains brief excerpts from three new

reports on U.S. counterterrorism interventions in the Sahel and

elsewhere in Africa, as well as excerpts from a report from the New

Humanitarian on new secret negotiations with jihadist insurgents in

Burkina Faso.

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on peace and security, visit

http://www.africafocus.org/intro-peace.php

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

AfricaFocus Bulletin is a strategic partner of the new US-Africa Bridge Building Project, and will periodically be including excerpts and short links related to that project.

Introducing Tax Justice Network Africa

Interview with Farah Nguegan, Manager, Communications, Campaigns and Outreach

March 2021

The Tax Justice Network Africa (TJNA), founded in 2007, has been one of the most active and successful of the regional federations working to stop tax evasion and illicit financial flows. Since 2015, the Mbeki report from the UN Economic Commission for Africa and the civil society Stop the Bleeding Africa campaign brought much wider recognition of the fundamental importance of tax justice to solving the critical problems both of Africa and of a grossly unequal world. Yet Covid-19 has made it clear that inequality is still being deepened, while a global elite continues to control a larger and larger share of the world’s wealth.

We asked Farah Nguegan of TJNA to answer a few questions. Click here to read the interview. — Imani Countess

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

U.S. Counterterrorism Operations in Africa

Nick Turse, “Stunning Classified Memo Details How U.S. Commandos Are Getting Beaten By Terrorists in Africa,” Vice, March 18, 2021

Full article at https://www.vice.com/en/article/4adzpb/secret-plans-detail-failures-of-us-commandos-in-africa

Excerpt: Special Operations Command Africa “is responsible for

countering the VEO threats in Africa,” reads a formerly secret set of

plans obtained by VICE World News. This “foundational document”

laying out SOCAFRICA’s “campaign activities” over the years 2019 to

2023, not slated to be declassified until May 2043, details how the

command intends to “achieve its mission of degrading, disrupting, and

monitoring violent extremist organizations over the next five years.”

But halfway through their campaign, America’s commandos are already

failing, according to a recent Pentagon report. That analysis,

authored by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, a Defense

Department research institution, paints a troubling portrait of the

security situation on the continent, showing a 43 percent spike in

militant Islamist activity and sharp increases in violence in 2020 as

part of a steady and uninterrupted rise over the last decade.

Nani Detti, “Assessing counterterrorism operations in the Sahel,” Center for International Policy, US-Africa Policy Monitor, February 23, 2021

Full article at:https://mailchi.mp/debbf09e76a5/the-continent-us-africa-policy-monitor-23-february-13356971?e=ab1b4c604e

Excerpt: For the last two decades, the U.S. has provided nearly $1.4

billion in security assistance to the G5 Sahel, and in the past few

years, France has spent 600 million euros annually to sustain its

military operations in the region. But despite their costly military

expenditures, neither the U.S. nor France have been successful in

stopping the increase in extremist violence in the region. The time

is long past due for both France and the U.S. to reassess their

militarized foreign policy in the Sahel and initiate a different

approach.

“Why the US’s counterterrorism strategy in the Sahel keeps failing,” by Frank Andrews

Mail & Guardian, 16 Feb 2021

Full article at: https://mg.co.za/africa/2021-02-16-why-the-uss-counterterrorism-strategy-in-the-sahel-keeps-failing/

Excerpt: In mid-2011, Matthew Page and his team at the United States

Defence Intelligence Agency (DIA) began to suspect something was awry

in Mali.

As the DIA’s senior analyst for West Africa, Page had access to

highly-classified signals intelligence from the National Security

Agency and reports from the department of defence (DOD) and CIA.

Together, they told a troubling story: one of corruption and

discontent in the Malian military, a long-term beneficiary of US

training and weapons that had recently sustained brutal losses to

armed groups in the northern deserts.

But Page, now an associate fellow with the Africa programme at

Chatham House, an independent policy institute based in London, felt

the diplomatic cables coming out of the US embassy in the capital,

Bamako, were painting a far rosier picture.

“We were pretty sceptical of how all this training and engagement had

magically transformed the Malian military into a much more

professional fighting force,” he said.

So, at their huddle of desks in the DIA headquarters in Washington

DC, Page and his colleagues wrote several reports on the fragilities

in Mali’s military.

“This narrative was really not welcomed by the ambassador at the

time,” said Page, referring to then-US ambassador to Mali, Gillian

Milovanovic, who “really savaged the assessment we made”.

She declined to answer questions about her recollection of this

exchange.

Analysts sometimes get pushback from ambassadors, said Page, who

spent more than a decade in government as an intelligence analyst

covering West Africa and Nigeria.

Page’s concerns proved to be well-founded. In March 2012, Amadou

Sanogo, a Malian captain who had trained in the US, overthrew Mali’s

democratically-elected government. It was a disaster for the US, who

for a decade had pumped tens of millions of dollars in counterterror

training and weapons into Mali.

“Nine months after [the embassy] received our note,” said Page, “the

elite unit had killed the other half of the elite unit we had trained

and buried them in shallow graves.”

*********************************************************************

Rethinking the Response to Jihadist Groups Across the Sahel

The solution to insurgency in the Western Sahel lies in human security and better governance, not military action

Chatham House Research Paper

2 March 2021

https://www.chathamhouse.org/2021/03/rethinking-response-jihadist-groups-across-sahel

Dr Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos

Senior Researcher, Institut de recherche pour le développement

The dominant narrative of a global jihadi threat has overshadowed the

key role played by military nepotism, prevarication and indiscipline

in generating and perpetuating conflict in countries of the Western

Sahel. This narrative has pushed the international community to

intervene to regulate local conflicts that have little to do with

global terrorism or religious indoctrination.

Mali offers a clear example of how structural failings that long

predate the ‘war on terror’ – evident in poor governance and weak

state security mechanisms – have been the main driver of the growth

of insurgent groups over the past decade. By contrast, the recent

experience of Niger, which shares many of the structural and

historical challenges faced by Mali, demonstrates that progress is

possible where deliberate steps are taken to achieve more inclusive

governance.

External actors – national and multilateral – see engagement in the

Sahel as critical, but a primary focus on insurgent groups as

terrorists limits the policy options available to them to help

promote regional stability and limit human suffering.

Reframing responses away from ‘hard’ counterterrorism towards a more

holistic view of human security, and an emphasis on tackling

underlying challenges of governance, impunity and development, may

offer a more durable route to peace and stability in the Sahel.

Summary

Rather than the ideology of global jihad, the driving force behind

the emergence and resilience of non-state armed groups in the Sahel

is a combination of weak states, corruption and the brutal repression

of dissent, embodied in dysfunctional military forces.

The dominant narrative of a global jihadi threat has overshadowed the

reality of the key role played by military nepotism, prevarication

and indiscipline in generating and continuing conflict in the Sahel –

problems that long predated the ‘war on terror’. Moreover, it has

pushed the international community to intervene to regulate local

conflicts that have little to do with global terrorism or religious

indoctrination.

Mali offers a clear example of this. The widespread use of poorly

controlled militias, the collapse of its army, two coups – in 2012

and 2020 – and a weak state presence in rural areas, on top of a

history of repression and abuse suffered by its northern population,

has done much more to drive the growth of insurgent groups than did

the fall of the Gaddafi regime in Libya in 2011, Salafist

indoctrination, or alleged support from Arab countries.

It is time to rethink the role of the international community and

acknowledge its limits in this context. Today, success depends first

and foremost on the goodwill (much more than on the capacity) of

political leaders to reform and renew their social contract with

citizens, especially in rural areas. International efforts that seek

to support military action against armed groups will fail as long as

impunity prevails and local armies can kill civilians and topple

governments without consequence.

The recent experience of Niger might not offer a model that can be

replicated in its entirety in Mali, or elsewhere in the Sahel, but it

demonstrates that there are possibilities for improvement. Though by

no means perfect, Niger’s democratic experience shows that it is

possible for states in the region to overcome the legacy of their

bloody and divided past.

01 Introduction

Structural problems that long predate the ‘war on terror’ underline

that poor governance and the weakness of state security mechanisms

lie at the root of violence in the Sahel.

The liberation war of Mali is over. It has been won. The intervention

of the French military has helped this country to recover its

sovereignty, restore its democratic institutions, organize elections,

and foster national unity. - Jean-Yves Le Drian, 2014 [French Defense

Minister at the time]

Rather than the ideology of global jihad, the driving force behind

the emergence and resilience of non-state armed groups in the Sahel

is a combination of weak states, corruption and the brutal repression

of dissent, embodied in dysfunctional military forces. These are

structural problems that long predate the ‘war on terror’, and they

serve to underline that bad governance and the weakness of state

security structures, including police and justice, lie at the root of

violence in the region.

Mali offers a clear example in this regard. The collapse of its army,

two coups – in 2012 and 2020 – and a weak state presence in rural

areas, on top of a history of repression and abuse suffered by its

northern population, have done much more to drive the growth of

jihadist groups than did the fall of Muammar Gaddafi’s regime in

Libya in 2011 or the rise of so-called ‘radical Islam’, the power of

Salafist indoctrination and alleged support from Arab countries. By

contrast, the relative resilience in recent years of Niger, a country

that shares many of the structural and historical challenges faced by

Mali, demonstrates that progress is possible if more inclusive

governance can be built.

In such a context, international responses that seek to support

military action against armed groups without tackling deeper

challenges of governance, especially in the domain of police, defence

and justice affairs, are very unlikely to succeed. The dominant

narrative of counterterrorism and religious extremism obscures

underlying political grievances and dysfunctionality, and the

widespread use of poorly controlled state-aligned militias to tackle

insurrection – in the absence of effective state military capacity –

has only served to fuel violence and worsen intercommunity tensions.3

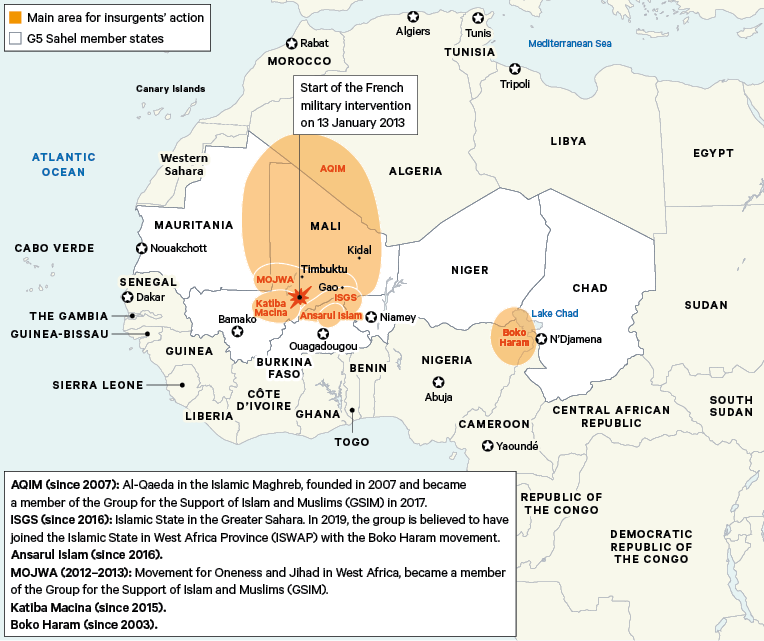

Figure 1. Jihadist group presence in the Western Sahel

Source: Map extract by the author and Eric Opigez, IRD-CEPED,

based on map published in Pérouse de Montclos, M.-A. (2018),

L’Afrique, nouvelle frontière du djihad? Paris, La Découverte, pp.

20–21; translations for this extract by Chatham House staff.

Note: The boundaries and names shown and designations used on the

map do not imply endorsement or acceptance by the author or Chatham

House.

It has also resulted in the pursuit of ineffective and often

counterproductive policy by international actors, which risks

building resentment among Sahelian governments and citizens alike,

and which over time may undermine the political will to maintain

costly military cooperation at all. Undoubtedly, insurgencies in the

region are a pressing issue. The ‘terrorist’ threat is the main

driver of foreign support in the Sahel. Yet it might not be as global

a threat as it is perceived to be, and its existence does not justify

why other unstable African countries receive less attention.

Moreover, international support always risks providing a security net

that deters the military and the ruling class from reforming

governance. In Mali, for instance, strong international support did

not prevent a coup in 2020 or the expansion of so-called jihadi

groups since 2013. Reframing policy away from hard-edged

counterterrorism towards a more inclusive view of human security, and

an emphasis on tackling the underlying challenges of governance,

impunity and development, may offer a route out of the acute policy

dilemma faced by those seeking peace in the Sahel.

…

07 Conclusion: the end of military cooperation?

In the context of complex and protracted conflicts, it is time to

rethink the role of the international community and acknowledge its

limits. Today, success depends first and foremost on the willingness

(much more than on the capacity) of corrupt leaders to reform and

renew their social contract with citizens, especially in rural areas.

International efforts will fail as long as impunity prevails and

local armies can kill civilians and topple governments without

consequence. Prospects for peace in the Sahel should not exclude any

option in this regard, from negotiating with jihadists to ‘naming and

shaming’ those responsible for abuses perpetrated by national armies

or their proxies, strengthening aid conditionality, or even

considering the possibility of disengagement.

A change in international community policy in the Sahel is

inevitable. France’s intervention in the Sahel has become

increasingly difficult due to resentment that has built up against

the former colonial power, particularly in countries such as Mali and

Burkina Faso with strong anti-imperialist sentiment dating back to

the Cold War era. Over time, French troops who were initially seen as

liberators have begun to be perceived as an occupying force, amid

suspicions that France is trying to gain control of resources and

markets: this view is echoed by some external observers. In 2013 the

French government even blocked the Malian authorities from sending

troops to Kidal – to avoid the risk of Malian soldiers massacring

civilians in revenge for the killings of Malian soldiers there – by

withholding the technical support, security and transport that the

Malian military needed in order to carry out its planned operation.

This act of obstruction was subsequently publicly denounced by

President Keïta in an interview with the daily newspaper Le Monde.

Not only does this damage the all-important goodwill that will be

necessary for meaningful reform. There is an additional risk that

continued setbacks will undermine political support within France for

continuing these international efforts. Operation Barkhane, in

particular, seems to have reached a peak in terms of public support

in France, given the difficulties experienced by the French army in

terms of recruitment, logistics and renewal of equipment. More than

50 soldiers have been killed while deployed to the operation since

2013, and some members of the French parliament have challenged its

continuation. Addressing the deep-rooted governance and development

challenges that drive violence in the Sahel, and the replacement of a

counterterrorism imperative with counter-insurgency approaches that

focus on human security, and recognize the importance of winning

hearts and minds, may be long overdue.

There are signs that some in the international community are

beginning to recognize these imperatives. In a report published in

2015, for instance, members of the French parliament highlighted the

contradiction of spending €1 billion a year on Operation Barkhane

while cutting development budgets without tackling the root causes of

the crisis. Some senators went even further in recognizing that

‘justice and the fight against impunity’ were probably ‘the first

demand of the people, before education or economic prosperity’.

Niger might not offer a model that can be replicated in its entirety

in Mali, or elsewhere in the Sahel, but it demonstrates that there

are possibilities for improvement. Not least through a high voter

turnout, the most recent presidential election, which took place over

two rounds in December 2020 and February 2021, has so far confirmed

the democratic foundations of the country. Though by no means

perfect, the experience of Niger shows that it is possible for states

in the Sahel to overcome the legacy of a violent and divided past.

Sahelian governments and their external partners alike need to learn

the lessons of history, both recent and of earlier decades, in order

to avoid a repetition of past mistakes.

*********************************************************************

Burkina Faso’s secret peace talks and fragile jihadist ceasefire

‘For us not to return to the jihadists, we expect the government to

help us and stop killing us.’

Sam Mednick, Freelance journalist covering Africa

New Humanitarian Exclusive, March 11, 2021

https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news/2021/3/11/Burkina-Faso-secret-peace-talks-and-jihadist-ceasefire

Djibo, Burkina Faso

In early October, Abu Sharawi got a call from his commander to lay

down his gun. He had been fighting for more than three years with a

jihadist group in Burkina Faso’s northern Sahel region but was told

an agreement had been reached with the government to stop the

attacks, which have killed thousands of people and driven more than

one million from their homes.

“[They said] ‘We decided to stop fighting. It’s time to sit and

discuss. Many people have died, and animals and resources were lost.

Using guns will not solve the problems’,” recalled 28-year-old

Sharawi.

Three men sit on the ground under a shelter, looking up at the

camera. The community in Djibo say they are caught in the middle

between the security forces, volunteer fighters, and the jihadists.

(Sam Mednick/TNH)

Seated in a restaurant in the capital, Ouagadougou, the now-former

jihadist said he was instructed to spread word of the ceasefire to

fellow fighters in his al-Qaeda-linked Group to Support Islam and

Muslims (JNIM) and return home. The New Humanitarian is using

Sharawi’s jihadist name to protect his identity in case of government

retaliation.

The government of Burkina Faso is publicly opposed to negotiating

with “terrorists”, yet a months-long investigation by TNH reveals a

series of secret meetings between a handful of high-level officials

and jihadists, beginning before November’s presidential elections.

That has resulted in a makeshift ceasefire in parts of the conflict-

hit West African nation with some of the extremist groups under the

JNIM umbrella, according to diplomats, analysts, jihadists, and aid

workers familiar with the discussions.

What remains unknown is what the overall goal of those negotiations

are, whether they extend beyond a ceasefire, and whether the dialogue

includes the Islamic State of the Greater Sahara (ISGS) – the other

major transnational extremist group operating in Burkina Faso.

The dialogue has nevertheless coincided with a sharp drop in

fighting.

Since 2016, jihadist-linked violence has been roiling Burkina Faso,

getting worse by the year. But according to research by the Armed

Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) – made available to

TNH – there were nearly five times fewer clashes between jihadists

and security forces from November 2020 to January 2021 compared to

the same period a year earlier.

Secret talks

In the months leading up to the November 2020 general elections,

several rounds of truce talks are believed to have been held in the

heart of JNIM’s area of violence, near Djibo town in Soum province.

They have been so secretive that even community leaders – normally

consulted on such issues – say they’ve been left in the dark.

TNH visited Djibo in February, becoming some of the first journalists

to do so in years, as the town is off limits due to the security

situation. Local residents said the jihadists, who used to come to

the market to kill people, were now coming to trade cattle and buy

motorbikes. Government officials and the police, who had fled the

town, were also beginning to return.

Since the beginning of October, locals say at least 50 unarmed

jihadists have been coming regularly into Djibo from surrounding

villages, or from camps in the bush. TNH spoke to two of them, and

both said they were ready for peace, as long as the army stopped

killing civilians – especially young Fulani men.

Soum province is a predominantly Fulani region. It’s a community JNIM

has allegedly drawn the bulk of its recruits from, with the promise

of a more equitable society and protection from both the security

forces and volunteer groups armed by the government who have targeted

Fulani men.

“For us not to return to the jihadists, we expect the government to

help us and stop killing us,” said Mohamed Taoufiq, a 27-year-old

fighter who told TNH he joined JNIM in late 2018 in revenge for the

army’s killing of civilians. Again, TNH is using only his jihadist

name to protect his identity.

What remains unclear is why the militants – whose leaders say they

are fighting for the establishment of an Islamic state across West

Africa – have agreed to the government's ceasefire offer, and how

long-term that peace can be.

Militarily, JNIM has been a particular focus of French-led Operation

Barkhane, a counter-insurgency mission aimed at uprooting jihadist

fighters across the Sahel. The al-Qaeda-linked group has reportedly

sustained significant losses, and there is speculation they may need

to reorganise, an analyst – who asked not to be named – told TNH.

Changing positions

News of the fragile ceasefire and peace talks with the jihadists in Burkina Faso does not come entirely out of the blue.

President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré has repeatedly stressed the need

for national reconciliation. In January, Prime Minister Christophe

Dabiré signalled for the first time he might be open to talks, saying

that for the five years of ever-worsening violence to end, the

government might have to “engage in discussions with these people”.

Although government spokesman Ousseni Tamboura told TNH no

negotiations were underway, he said the government was encouraging

religious and community leaders to reach out to jihadist recruits in

their areas to urge them to lay down their weapons and help rebuild

the country.

Community leaders, though, say they have received no guidance on how

to handle any potential local peace agreements – or on the

reconciliation and reintegration of defecting fighters. “We haven’t

received any information from anyone,” Boukari Belko, the chief of

Djibo, told TNH. “We are so confused.”

Until the government gives them the official “go ahead”, residents in

the town and nearby villages said they were too afraid to speak with

the jihadists – even though many of them are local and known to them.

They are worried the army might still accuse them of having links to

the extremists, and arrest them.

Human rights groups are also concerned that without a coordinated

response from the authorities on how to deal with returning jihadists

– and a clear strategy for their reintegration – the frustrated

expectations of ex-combatants could reignite large-scale violence.

“Even though there are negotiations today and people are coming back,

if they have nothing to do, they’ll return [to the fight],” said

Mamoud Diallo, executive secretary for Tabital Pulaaku, an

international Fulani rights group.

…

[more]

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication

providing reposted commentary and analysis on African issues, with

a particular focus on U.S. and international policies. AfricaFocus

Bulletin is edited by William Minter. For an archive of previous Bulletins,

see http://www.africafocus.org,

Current links to books on AfricaFocus go to the non-profit bookshop.org, which supports independent bookshores and also provides commissions to affiliates such as AfricaFocus.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please

write to this address to suggest material for inclusion. For more

information about reposted material, please contact directly the

original source mentioned. To subscribe to receive future bulletins by email,

click here.

|