|

2011 - African Migration, Global

Inequalities, and Human Rights: Connecting the Dots.

Current African Issues Paper for Nordic Africa Institute.

August 1, 2010 - Oped in Providence Journal U.S.-Africa 'reset' requires honesty about America's wrongs

President Obama has inspired hope in Africa and around the world.

Africans who heed his call to build the future, however, must still

reckon with the stubborn fact that the United States can be an

obstacle as well as a partner.

Spring, 2010 - Foreword to issue of Articulate -

End "Aid," Invest in Global Public Goods

Let us agree that the "aid paradigm" is fundamentally flawed, in that it is based on

a model of the rich "helping" the poor. But the paradigm advanced by free-market

fundamentalism, that poor countries and poor people can and should lift themselves

up by their bootstraps, without benefit of support from the wider society, is also

fallacious.

April, 2010 - Zimbabwe: Demystifying Sanctions and Strengthening Solidarity,

by Briggs Bomba and William Minter

In the case of Zimbabwe today, both supporters and opponents of

sanctions exaggerate their importance. The international community,

both global and regional, has other tools as well.

October, 2009 - Africa: Climate Change and Natural Resources,

by William Minter and Anita Wheeler

Africa will suffer consequences out of all

proportion to its contribution to global warming, which is

primarily caused by greenhouse gas emissions from wealthy

countries. But Africa can also make significant contributions to

mitigating (i.e. limiting) climate change, by stopping tropical

deforestation and ending gas flaring from oil production.

March, 2009 - Making Peace or Fueling War in Africa,

by Daniel Volman and William Minter, for Foreign Policy in Focus

html | pdf (283K)

Will de facto U.S. security policy toward the continent focus

on anti-terrorism and access to natural resources and prioritize

bilateral military relations with African countries? Or will the

United States give priority to enhancing multilateral capacity to

respond to Africa's own urgent security needs? If the first option is

taken, it will undermine rather than advance both U.S. and African

security.

February, 2009 - Inclusive Human Security: U. S. National Security Policy, Africa,

and the African Diaspora, edited for TransAfrica Forum html (150K) | pdf (2.8M)

Fundamentally, it is necessary not only to present a new foreign policy

face to the world, but to shape an international agenda that shows more

and more Americans how our own security depends on that of others. The

old civil rights adage that "none of us are free until all of us are free" has

its corollary in an inclusive human security framework: "None of us can

be secure until all of us are secure. "

April, 2008 - Migration and Global Justice, pamphlet written for American Friends

Service Committee

html | pdf (379K)

"As the global economy drives global inequality, movement across borders

inevitably increases. If legal ways are closed, people trying to survive and

to support their families will cross fences or set sail on dangerous seas

regardless of the risks. "

December, 2007 - "The Armored Bubble: Military Memoirs from Apartheid's

Warriors," pp. 147-152 in African Studies Review

html | pdf (70K)

"The books reviewed in this essay are a small sample of one genre of war

literature: detailed accounts of battle from the perspective of those among

South Africa's military veterans who have no question that they were fighting

a just cause in defense of their country. "

Jan 31, 2007 - Oped in Providence Journal

"Don't replay Iraq in Horn of Africa"

"Somalia is not Iraq, of course. ... But the similarities are nevertheless substantial. The United States and Ethiopia cut short efforts at reconciliation ... They disregarded Somali and wider African opinion in an effort to kill alleged terrorists. And while chalking up military "victories," they aggravated long-term problems."

Jul 8, 2005 -

"Invisible Hierarchies: Africa, Race, and Continuities in the World Order" (pdf)

"The failure to acknowledge race as a fundamental feature of todays unequal world order remains a striking weakness of radical as well as conventional analyses of that order. Current global and national socioeconomic hierarchies are not mere residues of a bygone era of primitive accumulation. Just as it should be inconceivable to address the past, present, and future of American society without giving central attention to the role of African American struggles, so analyzing and addressing 21st-century structures of global inequality requires giving central attention to Africa."

In Science & Society, July, 2005

Jul 8, 2002 -

"Aid—Let's Get Real"

"There is an urgent need to pay for such global public needs as the battles against AIDS and poverty by increasing the flow of real resources from rich to poor. But the old rationales and the old aid system will not do. ... For a real partnership, the concept of "aid" should be replaced by a common obligation to finance international public investment for common needs."

In The Nation, with Salih Booker.

Jun 21, 2001 -

"Global Apartheid" (pdf)

"The concept captures fundamental characteristics of today's world

order."

In The Nation, with Salih Booker.

Nov 3, 1992 - Oped in Christian Science Monitor

"Savimbi Should Accept That Democracy Worked in Angola"

"Just one month after Angolans peacefully thronged polling stations in their first multiparty election

ever, the conflict-battered Southern African country is on the brink of all-out war. ... The international

community, including the US, has been unanimous, in urging Savimbi to accept the election results, but Savimbi and his close-knit group of top officers remain both unpredictable and militarily potent. The new conflict, which appears to the starting, will be hard to contain."

April, 1988 - "When Sanctions Worked: The Case of Rhodesia Reconsidered", with Elizabeth Schimdt, in

African Affairs html (97K) | pdf (3.4M)

"Sanctions, while not the only factor in bringing majority rule to Rhodesia, made a significant

long-term contribution to that result. ... Moreover, more strongly enforced sanctions could have

been even more effective. If Rhodesia's petroleum lifeline had been severed and if South Africa

had not served as a back door to international trade, ... the country could not have survived

for more than a matter of months."

1968 -

"Action against Apartheid,"

in Bruce Douglas, ed., Reflections on Protest: Student Presence in

Political Conflict

"But the government usually seems to be a very distant and unresponsive target

[for anti-apartheid protests]. Therefore exposure of U.S.A. business involvement in

Southern Africa - by demonstrations, withdrawal campaigns, etc. - is at least equally

important.

|

Migration and Global Justice: From Africa to the United States

AFSC Life Over Debt Discussion Paper Spring 2008

pdf (379K)

http://www.afsc.org/lifeoverdebt

By William Minter*

*

William Minter is the editor of AfricaFocus Bulletin

(http://www.africafocus.org

)

People on the Move in the Global Economy

People have been on the move throughout human history. The ancestors of all of us

adapted to changing climate and diverse conditions within Africa, our common

continent of origin. Wars, famine, and other hardships have impelled countless

migrations over land and sea. From the 16th through the 19th century, the

transatlantic slave trade marked the most brutal of displacements which took

Africans to the United States and other countries of this hemisphere. In the current

era of globalization, economic disparities are driving accelerated migration. Often

the movement is forced by economic hardship; sometimes it is in response to new

opportunities. Most often the reasons have been and are a mix of push and pull.

Migration has always been driven by powerful economic and political forces.

Conditions have rarely been easy, as individuals adapted to change and communities

clashed or learned to live together. As the global economy drives global

inequality, movement across borders inevitably increases. If legal ways are closed,

people trying to survive and to support their families will cross fences or set

sail on dangerous seas regardless of the risks.

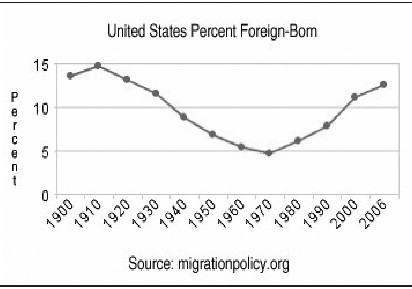

In the United States, immigrants were 14.7 percent of the total population in 1910.

This percentage dropped to 4.7 percent in 1970. It then began to rise again,

reaching 12.5 percent in 2006.

Almost one third of immigrants now in the United States were born in Mexico; 20

percent more come from five Asian countries. Almost 10 percent of immigrants, some

3 million people, are from the Caribbean, while those born in Africa--a group that

is growing rapidly--add up to more than a million. Caribbean immigrants have played

important roles in both the United States and their home countries, only a short

distance away, for more than two centuries. The African immigrant community is only

now moving into public life.

Almost one third of immigrants now in the United States were born in Mexico; 20

percent more come from five Asian countries. Almost 10 percent of immigrants, some

3 million people, are from the Caribbean, while those born in Africa--a group that

is growing rapidly--add up to more than a million. Caribbean immigrants have played

important roles in both the United States and their home countries, only a short

distance away, for more than two centuries. The African immigrant community is only

now moving into public life.

African Diaspora Migration: The Story of New York and Florida

Among recent immigrant communities, people of African origin from the Caribbean and

coming directly from the African continent are well represented in East Coast

states. In total numbers of immigrants, New York ranks second, with 4.2 million

compared to California's 10 million. Florida ranks fourth with 3.4 million,

compared to 3.7 million in Texas. New York and Florida each have more than one

million immigrants from the Caribbean. New York ranks first in African immigrants

with more than 120,000, while there are some 35,000 in Florida. One out of five

New Yorkers was born outside the United States. In Florida, almost one out of six

was born outside the United States. Such rapid change would require adjustments

even in the best of times. When economic times are hard, and job losses and budget

cuts put pressure on the working and middle class of all origins, it is easy for

frustrations to result in competition among communities and blaming other groups

instead of seeking common solutions.

The Vicious Circle of Global Inequality

The role of economic inequality

People may move for many reasons, but there is no doubt that one of the most

powerful forces driving international migration is economic inequality between

nations. There are rich and poor in every country, but the world's wealth is

overwhelmingly concentrated in a handful of countries. This means that a child's

chances of survival and of advancement depend on the accident of place of birth.

History makes a difference; over generations richer parents give their children

greater opportunities; and richer countries can invest in health, education,

technology, and other infrastructure that creates opportunities.

The division of wealth today is linked to centuries of conquest, slavery,

colonialism, and racial discrimination. It is also driven by a global economy that

rewards some and penalizes others, while powerful governments and special interests

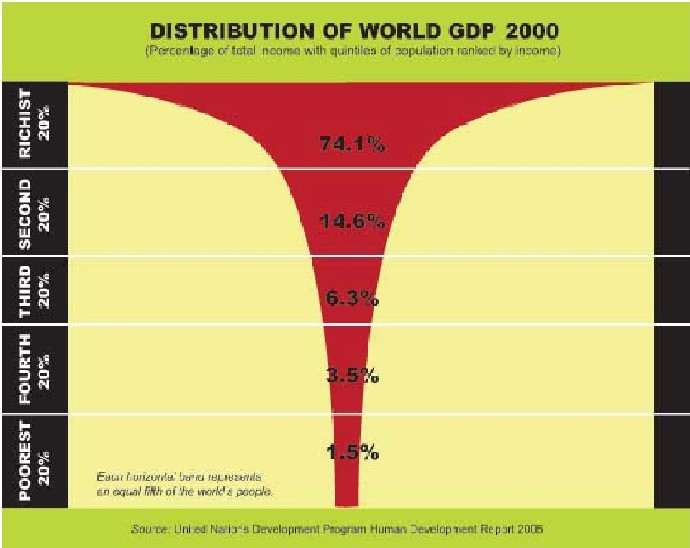

write the rules or apply them to their own advantage. In the year 2000, according

to the first comprehensive study of global wealth, the richest 2 percent of the

world's adults owned more than half of the world's total household wealth.

In such a world, it should be no surprise that people try to move to get a better

deal, and that many are not deterred by laws, fences, or danger. The phenomenon is

worldwide, wherever wealth and poverty coexist: Africans from around the continent

find their way to South Africa, South Asians find work in the Middle East, Mexicans

and Central Americans cross the border to the U.S. Southwest, people risk their

lives on small boats from Africa to Europe, or from the Caribbean to Florida.

Whatever governments do, people will continue to move as long as millions cannot

find a way to make a living at home.

In such a world, it should be no surprise that people try to move to get a better

deal, and that many are not deterred by laws, fences, or danger. The phenomenon is

worldwide, wherever wealth and poverty coexist: Africans from around the continent

find their way to South Africa, South Asians find work in the Middle East, Mexicans

and Central Americans cross the border to the U.S. Southwest, people risk their

lives on small boats from Africa to Europe, or from the Caribbean to Florida.

Whatever governments do, people will continue to move as long as millions cannot

find a way to make a living at home.

This global inequality is reinforced by economic mechanisms that are often

invisible and sometimes hard to understand, but that have powerful effects

including migration trends. But discussions of migration, and of trade, debt, and

aid, most commonly take place in isolation from each other. That is a mistake.

Trade gaps

Proponents of free trade say reducing trade barriers will eventually benefit all

countries. Some countries--such as rapidly developing China, India, and Brazil--

have sectors that may indeed be able to compete with richer countries. But neither

current practice nor proposed changes in rules for international trade offer a

fair deal for countries heavily dependent on the export of raw commodities or

lacking the industrial capacity to compete against international giants.

A couple of examples: The United States subsidizes large cotton farmers to the tune

of more than $3 billion a year. Those farmers can then sell their cotton on the

global market often at prices below what it costs to produce. This undercuts the

export chances of West African cotton producers where the average farmer already

earns less than $300 a year as they try to compete with world prices. Poultry

farmers in Ghana have been devastated by competition from frozen chickens imported

from Europe and the United States. In today's world, trade is essential for every

country. But unfair trade only puts vulnerable countries farther behind.

Although the elite in many countries can benefit, free trade has not proven to be

an effective way to reduce poverty. When borders are forced open through free

trade, many farmers cannot compete even in their own markets. This happened, for

example, to some 1.7 million Mexican farmers estimated to be displaced since the

North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). The result is that many are forced to

migrate to cities, the borders, and then abroad in search of a livelihood. The

same happens with West African cotton farmers, or with poultry producers in the

Caribbean driven out of business by large multinational food companies.

Debt traps

Africa's foreign debt (principal and interest on loans owed to Western countries,

commercial banks, and multinational institutions like the World Bank), is now

draining more money out of the continent than aid coming in. These debts, many

originally the result of deals between undemocratic governments and unscrupulous

lenders, have grown because of rising interest rates and penalties over time as

well as a continued dependence on loans. Moreover, conditions imposed on countries

seeking loans or debt relief, such as insisting that governments charge school and

health care fees for service, actually harm a nation's ability to reduce poverty

and break the chains of debt.

Sub-Saharan Africa borrowed $294 billion between 1970 and 2002. Africa has already

paid back 90 percent of this. But, with high interest rates, the debt still stands

at more than $200 billion. For some countries, debt cancellation campaigns have freed up money for health and

education. But Africa is still paying $2.30 in debt for every dollar received in

new "aid." The debt burden adds yet another barrier to providing health,

education, and jobs at home, and thus leads both ordinary workers and

professionals to seek other options outside their countries.

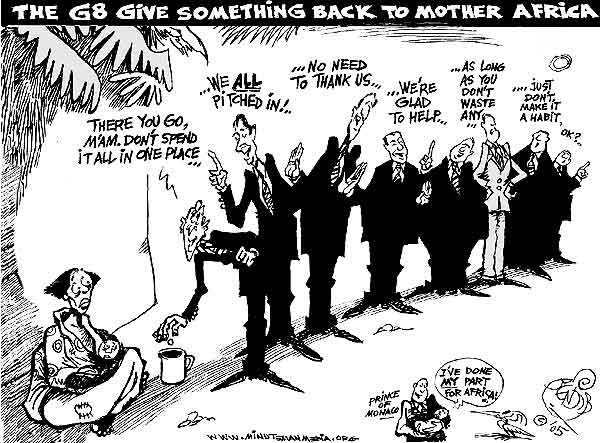

"Aid" reality checks

Despite many new promises and some genuine successes, such as increasing U.S.

and international support to fight AIDS and malaria, "aid" is still misleadingly

portrayed as charity rather than a basic obligation of world citizenship. The

United States is next to last among rich countries in the share of national income

put into "development assistance"--only 18 cents out of each $100 compared to the

target of 70 cents out of $100. As much as 90 percent of U.S. aid is what critics

call "phantom aid," much of the funds going to high-priced foreign consultants and

tied to purchasing goods from the donor country. In short, Americans are nowhere

close to paying our fair share to build a world that works for all of us.

As long as the money flows primarily from poor countries to rich countries, people

too will move in large numbers in search of a better life for themselves and their

families.

A Framework for Action

No short-term solution, whether high-tech fences or changes in laws, will resolve

the complex issues of immigration driven by accelerating global economic

interaction. Steps to "fix the system" must include not only medium-term reforms in

laws and procedures, but also long-term actions that can counter growing global

inequality. In the meantime, it is essential to find ways to protect the human

rights and immediate interests of both newcomers and those who are threatened or feel

threatened by the pace of change. Organized response from immigrant communities voicing their concern and contributing to

policy reform is critical.

The immigration system clearly needs fixing. More than 14 million newcomers,

documented and undocumented, arrived in the United States in the 1990s, and in

this decade there will be even more. As many as one-third of immigrants now in the

country do not have the proper legal documents. The U.S. border control budget has

jumped from $268 million in 1986 to some $13 billion 20 years later, according to

the Migration Policy Institute. States with large immigrant populations face

unsustainable budget crunches for services. There is competition between

immigrants and other groups for jobs and housing, increasing tensions among

grassroots communities.

Even a well-designed and fair immigration system cannot work as long as the

economy continues to increase the gap between rich and poor, both within and

between countries.

Principles for Comprehensive Immigration Reform in the U.S.

AFSC, May 2006

Inclusive and coordinated measures that support immigration status adjustment for

undocumented workers.

Support for the distinctly important and valuable role of family ties by

supporting the reunification of immigrant families in a way that equally respects

heterosexual and same-sex relationships.

Humane policies that protect workers and their labor and employment rights.

Measures that reduce backlogs that delay the ability of immigrants to become U.S.

permanent residents and full participants in the life of the nation and of their

communities.

The removal of quotas and other barriers that impede or prolong the process for

the adjustment of immigration status.

Guarantees that no federal programs, means-tested or otherwise, will be

permitted to single out immigrants for exclusion.

Demilitarization of the U.S. border and respect and protection of the region's

quality of life.

"Free trade" agreements like NAFTA and CAFTA have had a detrimental impact on

sending countries from the global South, provoking significant increases in

migration. Such international economic policies should be consistent with human

rights, fair trade, and sustainable approaches to the environment and economic

development.

Fixing the system

Trying to stop the flow of immigrants, without solving economic problems both here

and overseas, will not work. A redesigned system of immigration control, says the

Independent Task Force on Immigration and America's Future, needs rules that are

simplified, fair, practical, and enforceable. It should set realistic legal

immigration levels, and provide a clear path for legality for those currently

without documents. Any proposed reform must comply with certain basic principles,

as laid out in AFSC's May 2006 statement of principles (see sidebar, left).

Even a well-designed and fair immigration system cannot work as long as the economy

continues to increase the gap between rich and poor, both within and between

countries. Bottom line, both immigrants and non-immigrants should mobilize for

more jobs and more equality, rather than fighting over crumbs. Internationally,

rich nations must pay their share to address the world's problems, from poverty and

lack of education to disease and climate change. Countries that are closely linked

by the flow of migrants must coordinate their efforts to promote development and

decrease inequality. We must build a world in which the decision to move to another

country is driven by free choice rather than the pressure to survive.

Protecting human rights

Whatever the system, or whatever laws may have been violated, human beings are

never "illegal." International human rights law increasingly recognizes that

countries have the obligation to guarantee basic rights to immigrants as well as

citizens. These include, at minimum, the rights of humane treatment and due process

for all. Both countries of origin and countries receiving immigrants have the

obligation to ensure that these rights are respected. Long-term security will not

come from violating human rights, but from ensuring that they apply to all.

About the Africa Program

The Africa Program of the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) in the

Peacebuilding Unit (PBU) promotes the economic and political well-being of the

African continent. The program's goals include:

- increasing U.S. citizen understanding of issues affecting the African

continent;

-

standing in solidarity with Africa's social movements; and

-

promoting organized U.S. citizen action to pressure the U.S. government to develop a

just policy toward Africa, which will remove dated approaches and structures that

undermine economic and political development on the continent.

The Africa Program also works to end U.S. support for entrenched African governments

that do not respond to the will of their populations and maintain unjust economic

and political systems.

American Friends Service Committee

Africa Program * Peacebuilding Unit

1501 Cherry Street, Philadelphia, PA 19102-1403

The American Friends Service Committee is a Quaker organization that includes

people of various faiths who are committed to social justice, peace and

humanitarian service. Its work is based on the belief in the worth of every person

and faith in the power of love to overcome violence and injustice.

|